The Seven Hour City

I step off the run-down train onto the platform, and a bright, white light fills my vision. The beeping surveillance robot hovers away as my eyes adjust, and I begin to see glimpses of the world I’ve stepped into; the world after the war. They say it only took seven hours for the governments of Earth to surrender, and the evidence of that subjugation is all around me. A fleshy alien hunches over the broom it’s chained to. Loved ones anxiously await friends and family who will never arrive. A large arrivals and departures board displays cities stripped of their identities and compartmentalised, much like their citizens. I am herded through security checkpoints and dimly lit hallways. Eventually, I make it outside, to a quiet city square carefully watched by the occupying Combine forces, and overshadowed by the phallus-to-end-all-phalluses: the Combine Citadel. This is it. This is life in the Seven Hour City. City 17.

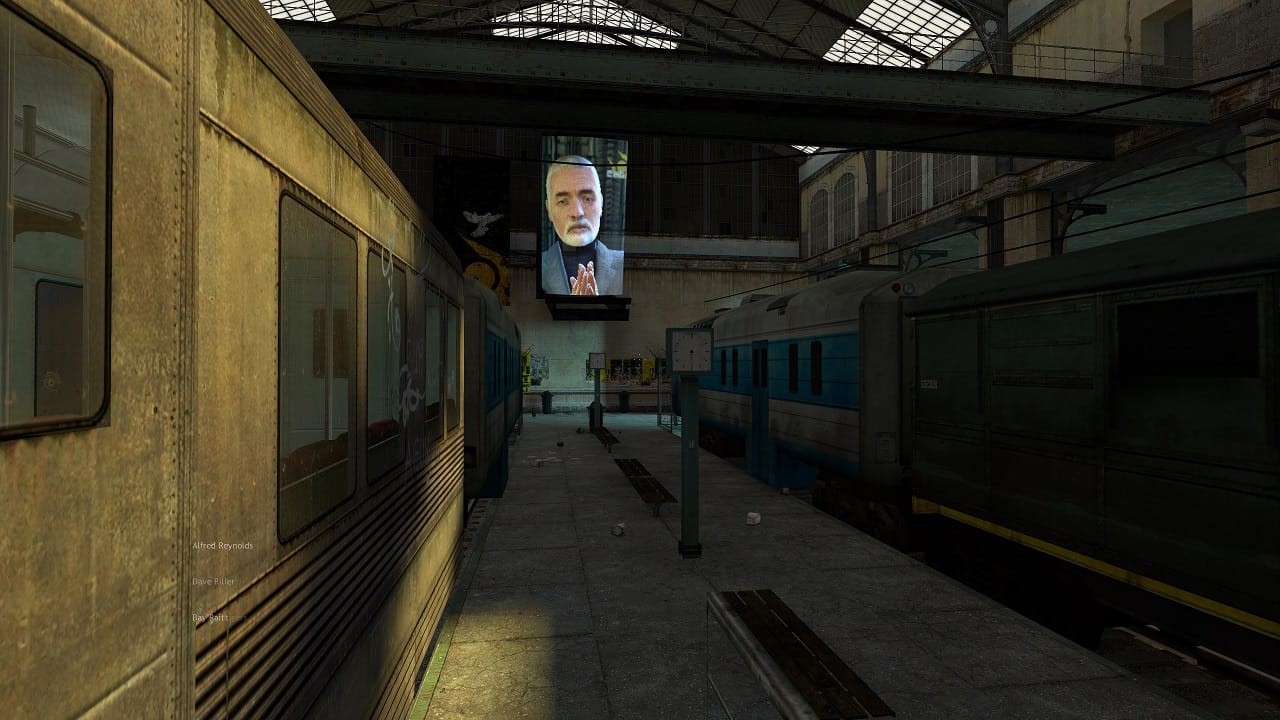

Despite being released over ten years ago, I still haven’t found an opening level quite as compelling as Half-Life 2’s introduction to City 17. With a meticulous level design and a strong commitment to the fiction of its world, it manages to convince you of your agency while still maintaining strict control over your navigation. From the very moment you step off the train, you are guided by the large, bright screen, the hard diverging lines adorning the carriages on either side of you, and the repeating posts and benches. You’re not being forced to take this path. You want to take it. To follow the appropriate path in Half-Life 2 is to follow your navigational instincts as a human being. In the physical world we like to think ourselves as totally free, able to go anywhere we feel like. But we don’t. We stick to the footpath, whether or not there’s a sign telling us to “keep off the grass.” We drive on the road, not on the sidewalk, and not just because there are laws against it, or we might cause harm to ourselves or others. There is a distinct, visual difference between the appropriate, intended path, and the unintended one, and in Half-Life 2, this difference is presented to you as “the illusion of free choice.”

The entire space reeks of restriction

Half-Life 2‘s lead environment designer, Viktor Antonov, weaves the power struggles and politics of the fiction into the design of the environments, to help guide in this navigation. As well as the imposing placement of the Combine soldiers and their architecture, the opening sequence utilizes real-world references to construct a believable vision of oppression and restriction. The city square recalls images of communist Europe during the 20th Century, with its wide range of differing architectural styles strictly organised into sharp blocks, which tower over the carefully surveilled space. The ruined buildings in the distance remind us of the shelled husks of Sarajevo during the Bosnian War, and large, inorganic walls very clearly mark where you can and can’t go, recalling the Berlin Wall. The entire space reeks of restriction, which in turn implies a world that exists just beyond your access. The ghosts of commerce, communication, movement, life, and art haunt this space, wandering between the aforementioned images and associations we all carry in our subconscious.

Anotonov’s environment design elegantly weaves these associations in with Half Life 2’s own fiction to design a space that feels so much more expansive than it actually is, where each navigational action made by the player is justified both within the logic of the space, and their own instincts. As the looming image of Dr. Breen lectures you on the irrelevance of instinct, you are pushed and pulled through this space, thinking you’re relying on those instincts, when in fact you’re abandoning them.

Nowhere else is this better demonstrated that in the various level design tricks Valve pulls on you throughout this sequence, creating a sense of disorientation through its manipulation of the elements of its environment design. It establishes certain unconscious “rules,” then disrupts them as you continue through the space. The bright screen, diverging lines, and repeating props of the train platform set a precedent as the correct pathway, but following this rule later on, in an abandoned courtyard, with trees that visually march toward a well-lit doorway, leads you straight into a Combine sting operation. The actual path is an open doorway just off to the side. This design philosophy again propagates the illusion of free choice by forcing you outside of the Combine’s strict guidance, convincing you that you’re breaking the rules, when in fact you’re just following a different set.

It’s a tactic similar to those used by police recently in protest movements across the world, where designated protest zones are established, creating the illusion of free movement, when it is closer to a tolerated movement. In fact, it’s becoming increasingly fascinating, even eerie, to revisit the opening of Half-Life 2, given the recent protests in London, Baltimore, and Ferguson.

The architecture and tactics of the Combine start to look awfully familiar when paired with the images supplied by news outlets during these events. The large, metallic gates used to contain and guide protesters in London are similar to the large, metallic gates used to contain and guide the citizens of City 17. The images of over-militarization in Ferguson and Baltimore, including advanced weaponry and vehicles on suburban streets, recalls images of Combine-led arrests during the opening moments of the game. Even the Citadel itself sends a very similar message: we are bigger, we are stronger, and we are better. We can build this. The politics and power structures of these protest events are made clear by how they are organized and controlled, just as the architecture and allocation of space under the Combine’s City 17 make clear its fictional politics and power structures. By reading into these spaces we can see how these structures operate, and by extension, how they can be combated. The design and positioning of the Combine’s architecture, the way it clings onto the crumbling buildings and digs into the concrete, suggests a very dependent, parasitic relationship, for example. The Combine only have power as long as the citizens of City 17 afford them that power.

Similarly, by examining how real world authorities attempt to prevent or contain large-scale public gatherings, it begins to become clear how these methods could be counteracted, if necessary. Police try to segregate and contain the crowds, so protesters spread out and occupy well-trafficked spaces, such as streets immediately outside Flinders Street Station in the recent sit-down protests in Melbourne. Authority tries to make protestors’ movement slow, and predictable, so instead they move quickly, fluidly—the protestors react at a moment’s notice, as in the London riots. Protestors are barred from communicating, so they utilise social media to connect cities, movements, and groups.

Similarly, the Combine keep the light shined on the citizens of City 17, and funnel their movement through open, public, observable spaces, so as Gordon Freeman, we explore the secret, the underground, and the abandoned spaces; the quiet courtyards, the gaps between buildings, the sewers. No matter how hard the Combine try, no matter how much ground they think they’re converted, there is always a way to fight back.

there is always a way to fight back.

Spaces are a mirror of the society in which they exist. Virtual spaces then, by extension, are a mirror of the various ways in which a player is allowed to interact with that space. Half-Life 2’s introduction to City 17 is special, because it accomplishes both. Like the Combine forces which rule it, it makes you feel free, when in fact you are anything but. Valve ties their fiction into their level design through jagged, inorganic architectural constructs, a sharp level design which establishes and disrupts its own internal rules, and its associations to instances of public oppression and control, both past and contemporary. It provides a useful lens through which to view the modern protest landscapes of London, Baltimore and Ferguson, and allows us to see how these systems of power could be disrupted. The genius of Half-Life 2’s opening chapter is not that it’s clear in telling you where to go. It’s that it convinces you that it’s where you wanted to go all along.