Shakers, machines, & desert Pigs: Vinny Roca's devotional designs

Play becomes prayer; objects transform into beings; digital devotion meets industrial design. Vinny Roca's work inhabits the spaces between traditional art practice and game development, where everyday items take on new life through animation and interaction. His latest works form a triptych of digital meditation - Easy Shaker Yolk Face examines 19th century religious labor through animated objects, Slot Waste traces absurdist production cycles that transform sacred into mundane, and Come Away With Me orchestrates an otherworldly desert ritual where pigs become performers in an evolving soundscape.

We spoke with Roca about contemplative objects, the poetry of procedural animation, and finding spirituality in the spaces between player and screen. His work reveals how digital interactions can reframe our relationship with the material world—whether through animate furniture carrying echoes of Shaker craftsmanship, industrial processes that pulse with dark humor, or pigs wandering a desert landscape to the ethereal sounds of Nora Jones.

WARREN: Tell me about your background and professional path into game-based art. What attracted you to the space, and how did you decide on games as an expression of your creativity?

ROCA: It started during my undergrad, where I focused on studying drawing and painting. After graduating, I was doing mixed drawing and performance work, using instruction-based practices similar to the Fluxus art movement, where audience members participate in actions you've designed. Concurrently, I was working as a 3D modeler and animator. I began incorporating these 3D models into my instructions as images to guide gallery visitors in engaging with different objects.

Then I started thinking: what if the instructions lived with these 3D models, rather than remaining analog instruction-based works? That's where I started making games. The first game in the exhibition, My Easy Shaker Yolk Face, came directly from that thought - what if I joined these instructional works in a game engine environment?

It was a natural progression. I had the 3D modeling skills and programming experience from my day job, while my art practice was more conceptual and instruction-based. Once I combined the two, moving into games as a creative practice made perfect sense.

"My Easy Shaker Yoke Face" (2021)

WARREN: The Fluxus movement seems to be a common touchpoint for people bridging the gap from non-digital art practices to engage with broader questions around play and interactivity. Could you tell me more about your interactions with that movement?

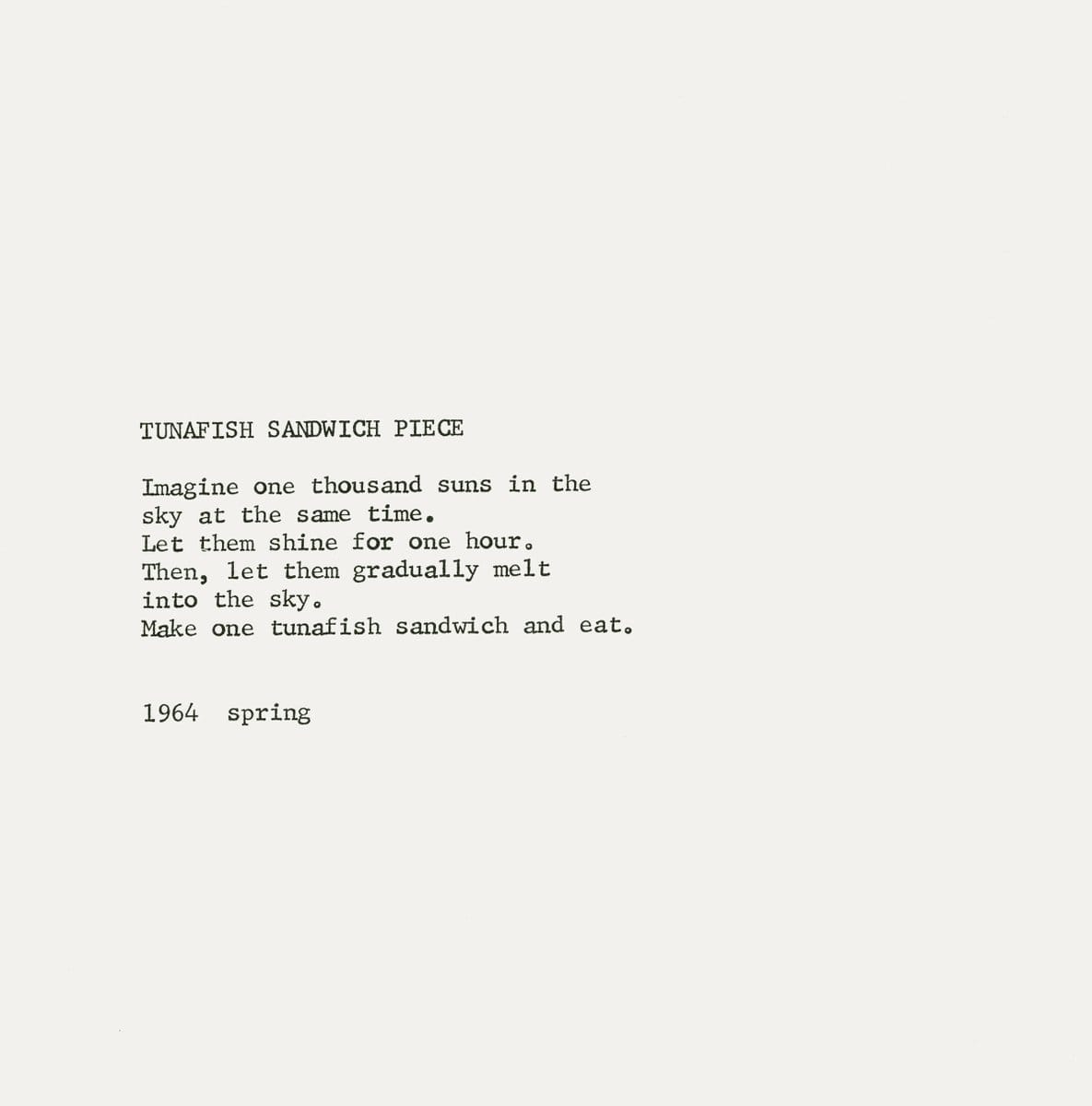

ROCA: For a while, I didn't think I was making games—I thought I was making conceptual instructional works in the footsteps of artists like Yoko Ono. Her pieces were very inspiring to me. She has one work called TUNAFISH SANDWICH PIECE where you look at the sun a certain number of times, and then after you've looked at the sun for that duration, you make a tuna fish sandwich and eat it. These conceptual artworks, part of the Fluxus movement, bridge the gap between play and what might be thought of as high art or fine art. They suggest that any action somebody undertakes could be considered artful if it's designed, instructed, or followed through with intentionality.

That's what games allow - a very intentional experience over a set duration. The Fluxus notion of play involves experimenting with both actions and language. I think of Yoko Ono and many Fluxus artists as playing with language and treating it as a space for experimentation. I see a direct line to the game engine - for my work, the game engine feels like what language was for Yoko Ono's work.

WARREN: There's an invitation there for people to experience the work. From an instructional design standpoint, what did you notice about how Fluxus artists constructed their designs and situated their instructions? What kind of experience were they hoping people would have?*

ROCA: The structuring of experience to create unexpected relationships between things plays a large role in my work. Take that TUNAFISH SANDWICH PIECE example—in language, she draws this connection between the sun and the sandwich, which gets you thinking about relationships. How the sun provides energy to things in the ocean that the tuna fish is eating, and then you're joining that into your own biological systems by consuming the sandwich. These instructions verge on the absurd, but when those juxtapositions are made, you get new kinds of meaning-making that create new potentials to relate different objects to each other.

I think about video games in my practice as experiences where different objects are set into new modes of relationships. They're virtual, but they have relationships to existing objects or objects of thought. In the game engine and game art, you can put those objects into relation with each other to conjure new meanings and point your audiences in different directions they might not have gone otherwise.

WARREN: Your work shows a deep focus on individual objects that require meditation and study. One challenge with making games is that from an asset standpoint, there are so many things that can be made. Making decisions about what to focus attention on becomes really important. Many games take this for granted by not creating meaningful relationships between individual objects, or by deferring to relational contexts that are given - working from a fantasy universe where the meaning is already coded into it. This often shuts the door for absurdity or non-diegetic objects to exist in those worlds. Your work stands out both in its focus on individual things and its sense of surprise and serendipity through unexpected combinations.

We had a conversation with Jenna Caravello about how important it is for animators to focus on individual objects as part of their craft. Could you tell me about your approach to 3D modeling individual objects? This really comes through in My Easy Shaker Yolk Face—there are so few things in the room, but the things you spend time with, you really spend time with. How does this connect to your previous non-gaming work?

ROCA: There's a distinct difference. Both works examine objects in production and their transformation through machines, but they approach it differently. In "Easy Shaker Yolk Face," I focused on objects created by members of the Shaker religious tradition in late 1800s America. I was particularly drawn to their relationship with objects through their religious lens—their famous saying "hands at work, heart to God." This philosophy suggests that when one becomes fully immersed in their labor, the body almost dissolves into the production process, allowing for a deeper spiritual connection and contemplation.

This led me to concentrate on contemplative objects and how they could become sources of complete attention. It marked a significant shift from my earlier instructional works, which centered on everyday objects—pieces about air conditioners or an urn filled with pistachios. Those were existing objects I found or purchased, asking visitors to focus their attention on them and their relationships. Moving to creating the objects myself was a substantial transition.

WARREN: What inspired you to add faces to these objects?

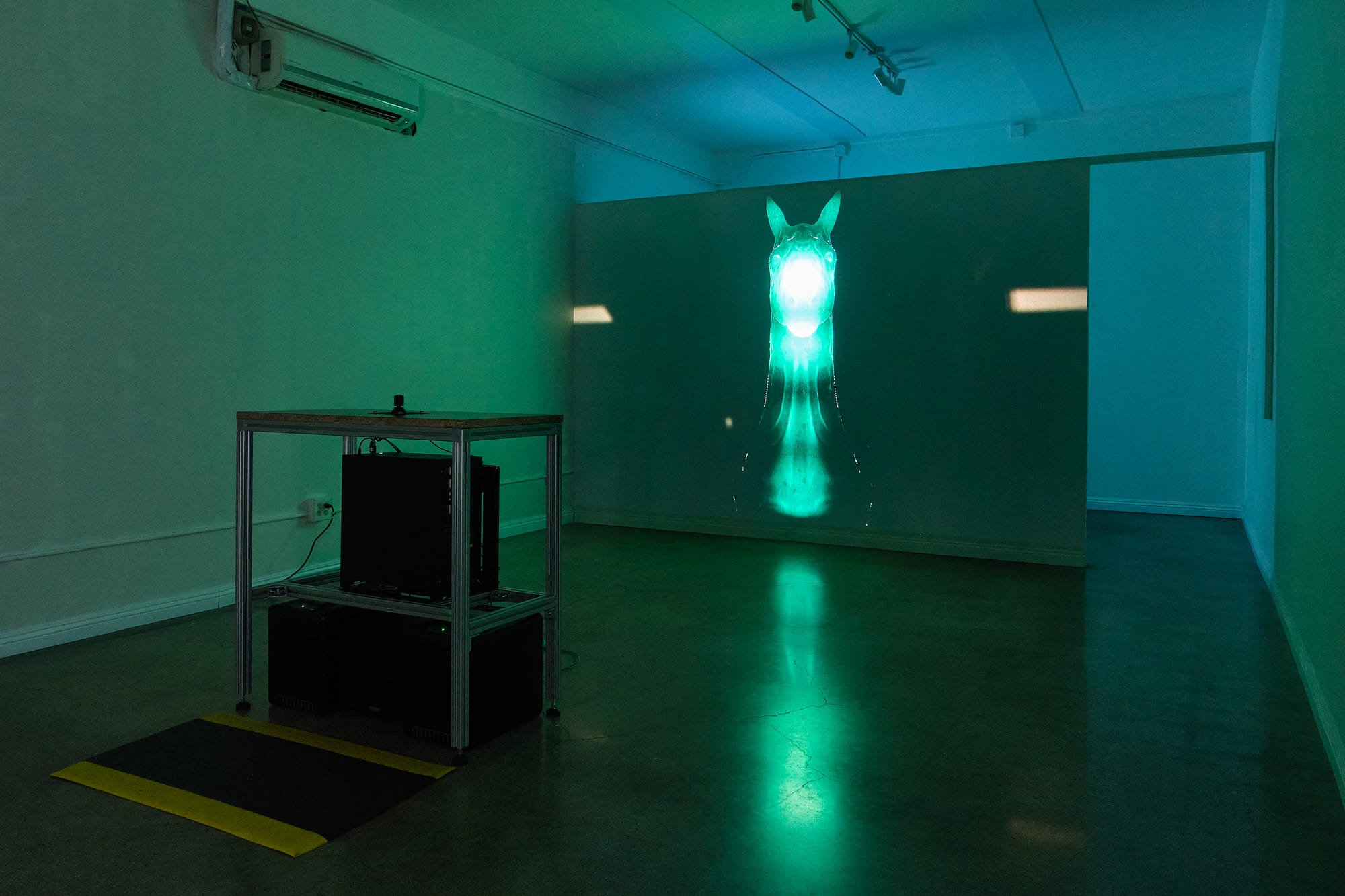

ROCA: One of my first impulses was to make the objects as unfamiliar as possible. Adding faces became this powerful gesture—when you put a face on something, it transforms into something entirely new. Our relationship with it shifts completely, allowing for this strange projection onto the object as a being. Taking it further by animating it gives it an almost life force that you, as a player or gallery viewer, must contend with during interaction.

Many of these gestures that I initially thought might be humorous or absurd, especially in Slot Waste, evolved into something more complex—almost becoming gestures of cruelty. You're interacting with these seemingly living things as they're processed through machines, and you're not always certain about what you're doing with them. The work really questions how our relationships with non-objects and objects, or non-beings and beings, are structured through this concept of the object—considering the animal as an object, the machine as an object, or even at times, people as objects processed through these machines.

The object became central because of its potential for transformation. At its core, it's about how an object plus time can equal something entirely new.

Your reference to the Shakers is interesting, given other Christian traditions that focus on attention as a form of devotion. How do you see this playing out in your games, particularly the contrast between "Easy Shaker Yolk Face" and your other works?

There are these other Christian traditions that focus on the importance of attention—whether monastic traditions or the spiritual tradition of Simone Weil—where attention to a thing or person becomes a form of prayer or devotion. Games offer a unique way to encourage players to spend that time. Playing "Easy Shaker Yolk Face," I felt a sense of care in my interactions, but you seem to subvert that in other works. The attention shifts toward acts of apparent cruelty or objectification—whether it's birds or walnuts, the objects' individual significance changes.

How did you come to focus on the Shaker tradition?

ROCA: I've long been interested in what you might call off-center Christian religious practices. Being raised Catholic, the transformation of objects has always resonated in my work. I discovered the Shakers through reading Thomas Merton, the American Catholic writer known for works like "The New Seeds of Contemplation," which examines life transformation through contemplative practices.

What particularly drew me to the Shaker tradition was its distinctly American quality. They weren't just crafting objects for contemplative purposes—they were selling these objects to fund their communities. This connection to capital fascinated me—it was religious labor that intersected directly with industrial capitalism of their time, much like what we see today. This relationship influenced Easy Shaker Yolk Face, examining what happens when that labor becomes absurd. This theme continues in "Slot Waste," where absurd labor loops endlessly, perpetually disconnected from reality.

WARREN: The Shakers represent a unique American religious expression from the 19th century, alongside movements like the Millerites and the Mormon tradition. While Catholicism developed distinct expressions during colonization, it maintained a central church. American Christian traditions often emerged independently—some enduring, others fading into history books. What's remarkable about Shakerism is how it persists through their objects, through their pursuit of perfection in craftsmanship. They left a tangible legacy through their beautiful furniture, unlike some other distinctly American religious movements.

Your relationship with capital as a game creator is particularly interesting. You're working with digital goods where scarcity functions differently than in the Shaker tradition. Has this created any tension in your thinking about distribution through digital platforms, or how you make your games available for sale? In a way, you're creating digital objects to fund your practice, similar to how the Shakers funded their communities.

ROCA: This relationship with digital goods is something I've been considering carefully. I make all my work available for free on itch.io, occasionally accepting donations. Recently, I've been thinking about approaching this differently—perhaps focusing on the original artifacts that inspire these games as the unique, salable elements. All my work begins with intense periods of drawing and sketching. These drawings are where the objects originate, as I work out their compositions on paper before sculpting them in ZBrush or Maya.

I've been examining the relationship between these initial drawings and the final digital experience. Since it's an interactive experience—a game—I struggle to assign it monetary value because it's infinitely reproducible. For me, the monetary value of the digital component approaches zero. I've considered making the original drawings available as a way for people to contribute to the work and connect with the design process.

WARREN: This is a common challenge for digital creators. Traditional artistic practices have inherent scarcity driving their value, providing artists with a clear path to support themselves. For those working with digital goods, it's significantly more complex. There are alternative support mechanisms like grants or fellowships. The trade-off is that digital creation has lower overhead costs—essentially just software licenses and time, unlike large sculptural works. While this makes exhibition easier, it creates unique challenges in determining what to offer supporters. How has making your work freely accessible impacted its reach?

ROCA: At this point in my artistic practice, I find real joy in releasing these works for free and watching people from all parts of the world stream and discuss them. I'm not certain this level of engagement would happen if I added a price barrier. It brings me genuine happiness to see people from different countries experiencing the works, even when I don't understand the language they're using to discuss them.

Most of my games intentionally avoid language barriers, giving them this international resonance that I really appreciate.

WARREN: Yes, they're truly legible without language. This accessibility across linguistic and cultural boundaries seems central to their impact.

ROCA: Absolutely. I was going to say that was kind of a key thing for me when I moved from the instructional practice to the more visual practice—trying to figure out a way to do all of the things that I was doing, these instructional or suggestive works, without having to fall back on the written word as a way to structure experience. But how could the objects themselves, and how could the placement of them, structure how people navigate the virtual space? In a sense, using the objects almost as you might use language or words?

WARREN: Yeah, a hundred percent. That makes sense. Not to go back to the Shakers, but I do think that the context for the Shakers in this pre-industrial age is key as well. They're trying to navigate creating physical goods that would become mass commercial. It just speaks to maybe a contemporary moment or tension for me as a creator. I think you can see why they raise a lot of big questions.

Well, I do want to talk about Come Away With Me. We showed Henrik Soederstroem's work and it does live simulation as well. I just think that is such an exciting area and usage of game engines—that you have something that is procedural but systematic. There's repetition, but you are allowing other systems to sort of control the experience for a player. Can you tell me a little about the origin of that work? I'm interested from a construction standpoint—what is designed, what have you turned over to Unity, and where are the things that you still want to make sure that you control?

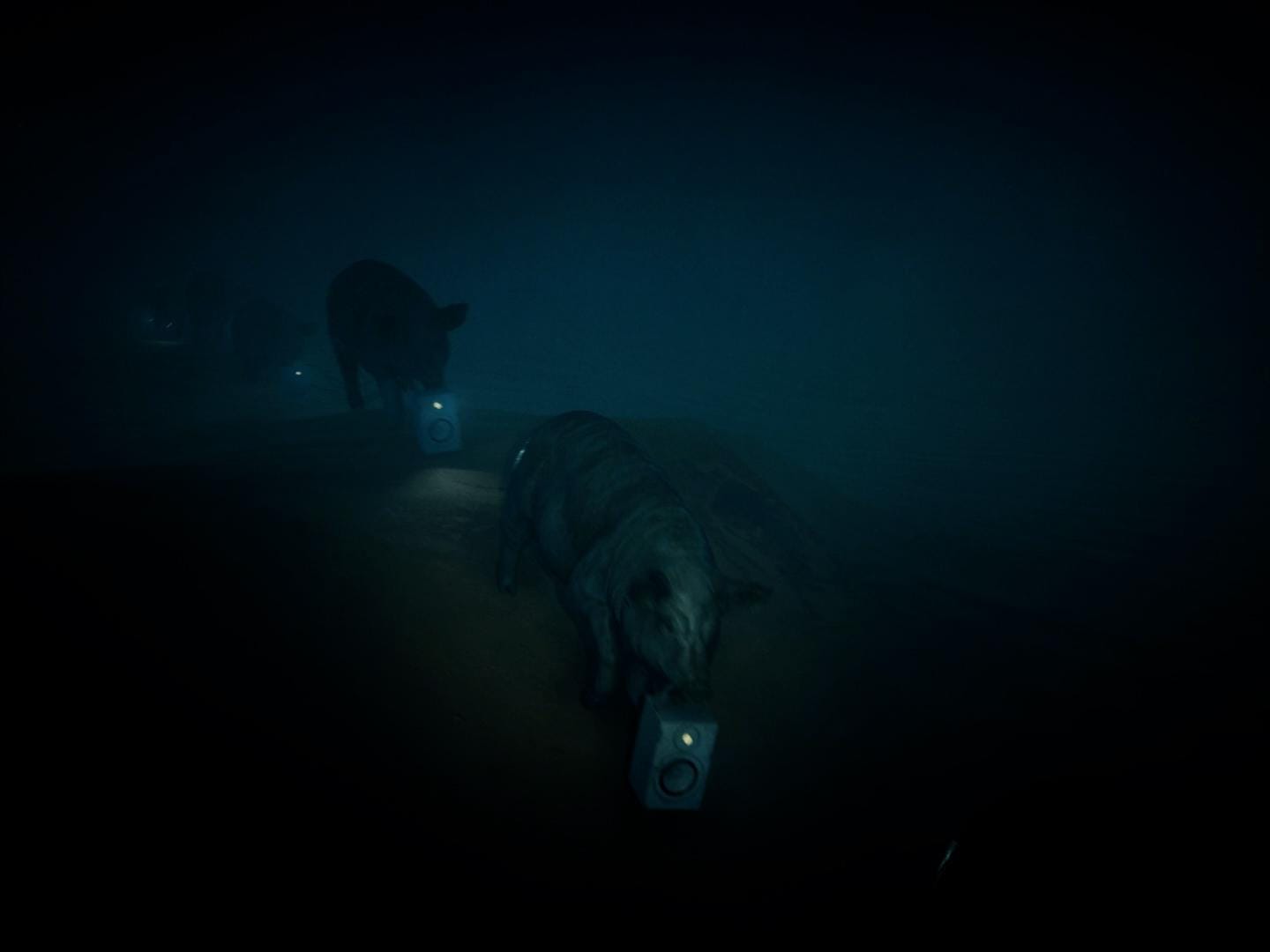

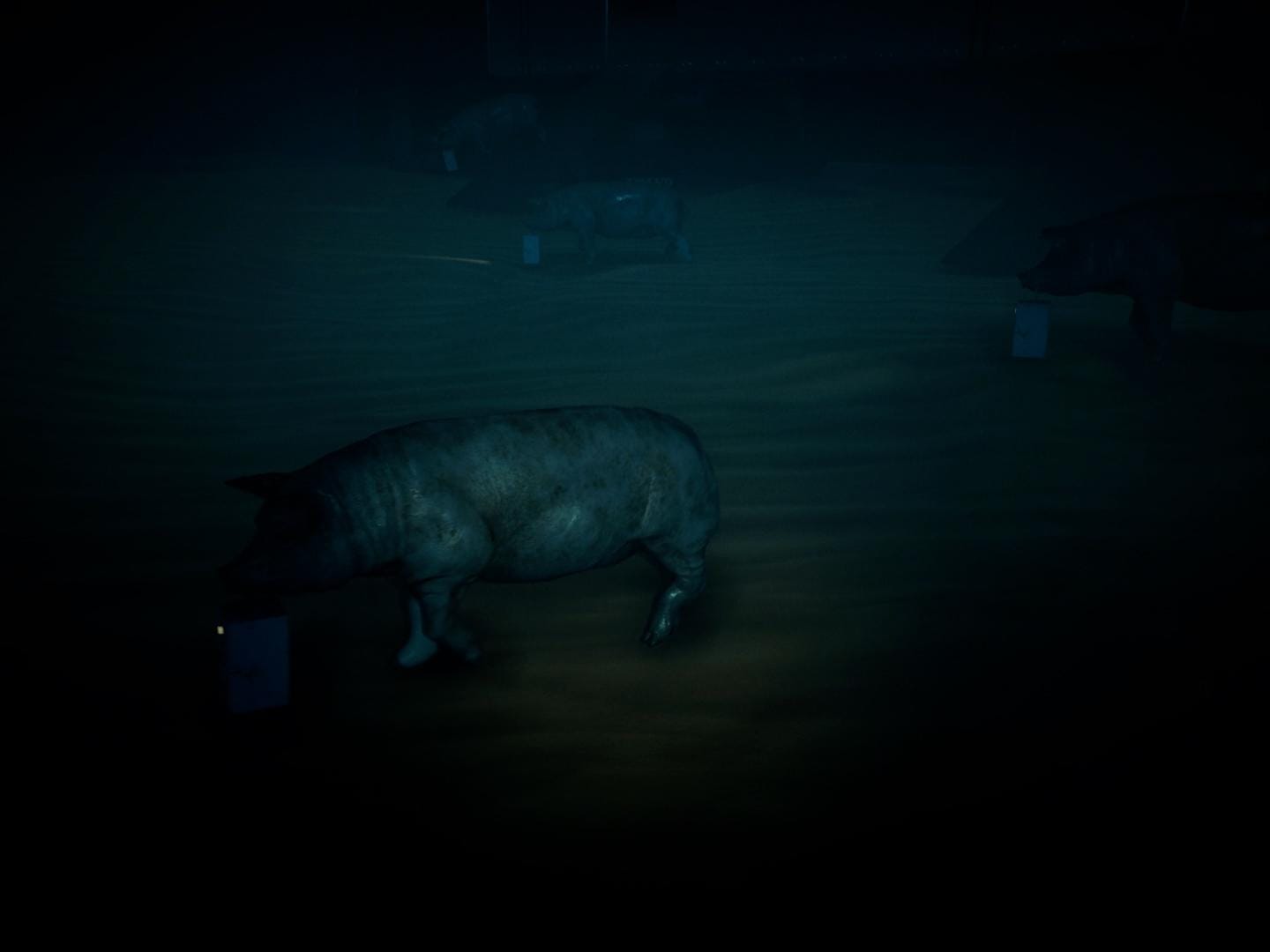

The work comes from a long line of investigation I've been doing with pigs, thinking about them as a born product — animals maintained and produced by large industrial systems. While they exist as wild animals, the pigs we typically encounter are sustained through these industrial frameworks. Unlike chickens or cows with their various byproducts, pigs occupy this contested space between object and living creature. This returns to core ideas I'm examining: when does a larger system transform a living being into an object?

My connection to pigs runs deep — I grew up around them, as my grandfather raised them. Being around these extremely intelligent animals left an indelible mark on me. There's something fascinating about them as strange, intelligent creatures that we, by our standards, consider very gross. This contrast drove me to design a performance where pigs could have some alternate ritual or way of existing, at least in a digital space — something that maintained a connection to our reality while creating an eerie breakage point beyond easy comprehension.

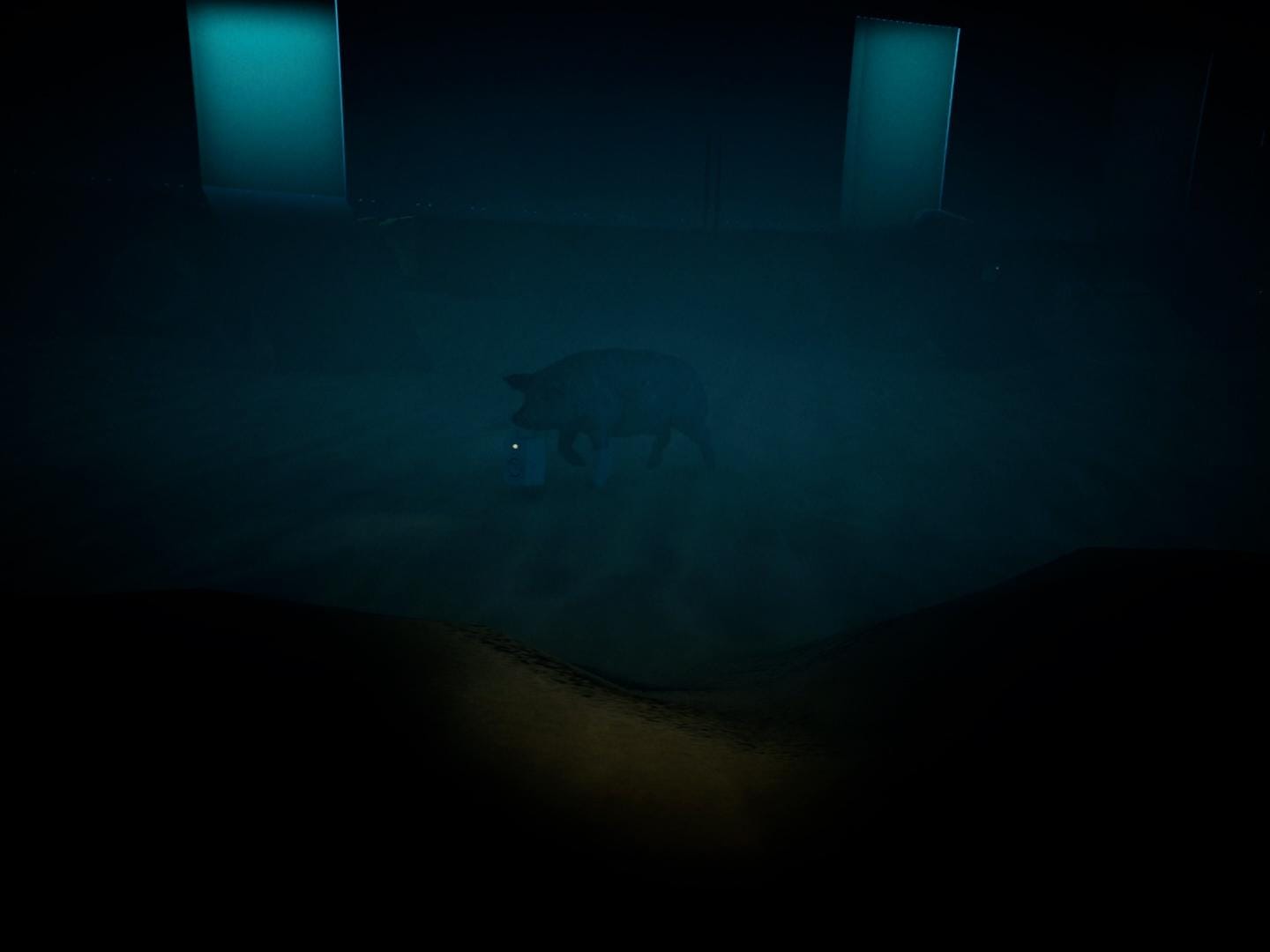

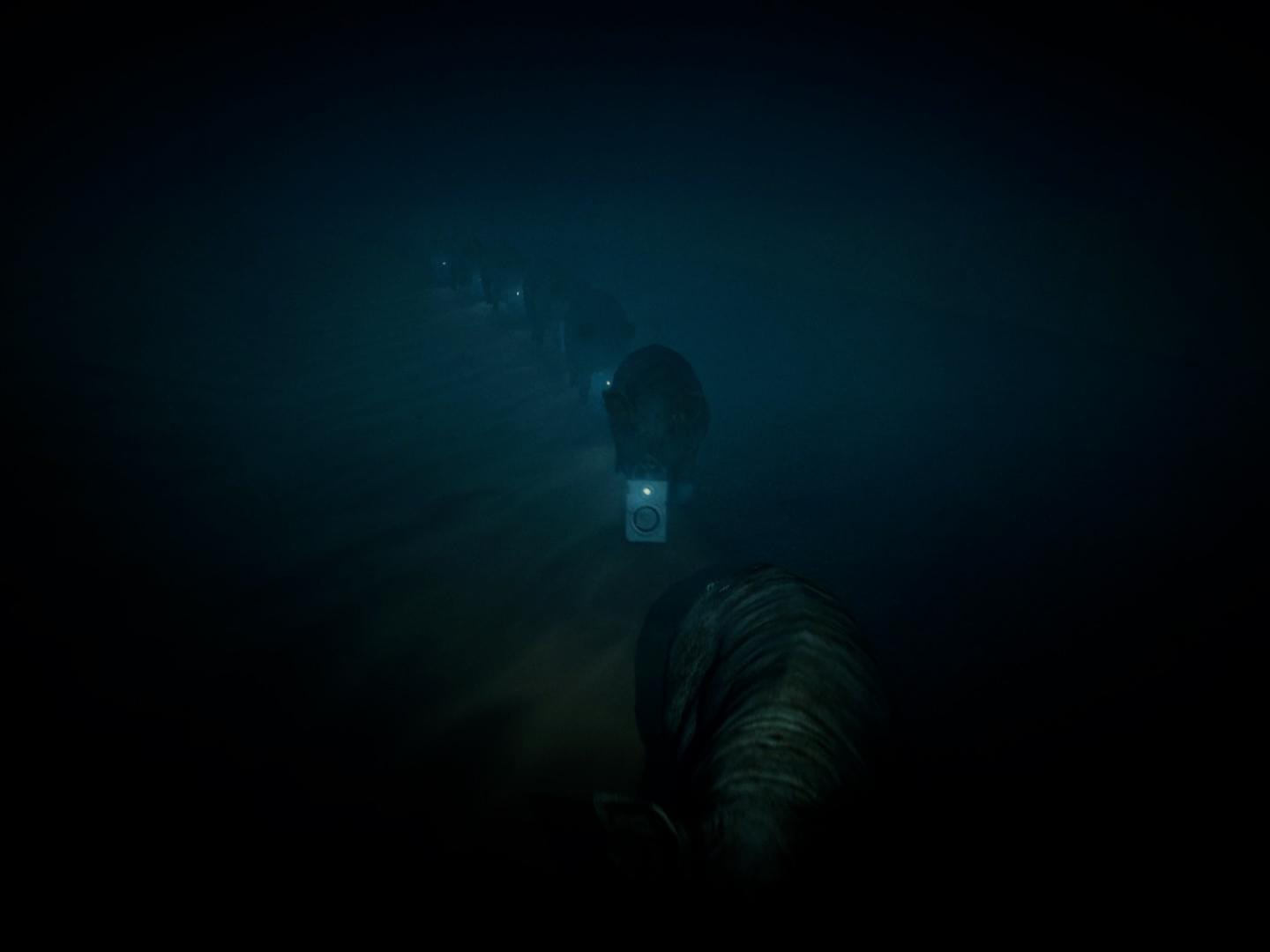

The ritual begins with a trailer parked in the middle of a desert. Each pig emerges carrying a speaker playing a song from Nora Jones's 2002 album "Come Away With Me." While their emergence is scripted, the song selection is controlled by procedural code — random but intentional. Their first task is finding a space to place the speaker, determined by hidden variables that form their internal decision-making mechanism. These variables aren't exposed to the viewer but guide each pig's choices about placement.

After setting down the speaker, they circle it in a complete 360-degree rotation, retrieve it, and return to the trailer — triggering the next pig's emergence. This continues exponentially until all the album's songs are represented. The pigs then follow in a long procession around the desert before returning to the trailer.

The camera work is entirely procedural, with parameters determining which pigs to follow and variables controlling distance and focal length. This creates fascinating compositions, though sometimes it might focus on the sand while the ethereal Nora Jones echoes across the desert — I find these unexpected moments particularly compelling. The pigs' movements are also procedurally controlled. I think of them as performers working with a script but having numerous options within those parameters to make their own decisions.

WARREN: This work deals with cycles, both individually with the pigs and in aggregate with the album. In Slot Waste and similar works, you create these interesting miniature cycles of performance and activity that are part of a larger cycle. It reminds me of perichoresis in Catholic and Christian tradition — you're creating these little circular instances that are ultimately connected. From a design standpoint, when you're thinking about creating these experiences, do you have the overall arc determined before figuring out the loops that populate it? Or do you start with these little loops or activities and then work out how to connect them? With Slot Waste, I can see how you could start with either approach.

ROCA: I design the overall system first, then create small pockets where I can work completely intuitively. At a certain point, I find relationships amongst things. With “Slot Waste,” I knew from the start I wanted this Rube Goldberg-like production process where one thing would lead to the next, but I had no idea what those individual things would be. It really spun out in a linear process. Many people have told me they're surprised by what turns into what — and I think that reflects my working process. I would do whatever felt very surprising to me as the next jump or gesture.

Even in the beginning, where the teapot head is filled with metal balls that are then melted to melt these bison — it was about finding these strange connections. I knew it would be filled with small bits of metal, so I'd think: what could happen to those pieces? What kind of processes of transformation could occur? The first thought would be they could melt. Then: what if they melted onto something? I'd spend time figuring out what would be meaningful for something to melt — what would have resonance?

I think about certain ideas I want to address, like the massacre of bison in America during the late 19th century. These become not quite exact representations, but influences and things to consider — always thinking about how these things pass between objects and being. I make them serious but look for where they could be funny, where they could be subverted.

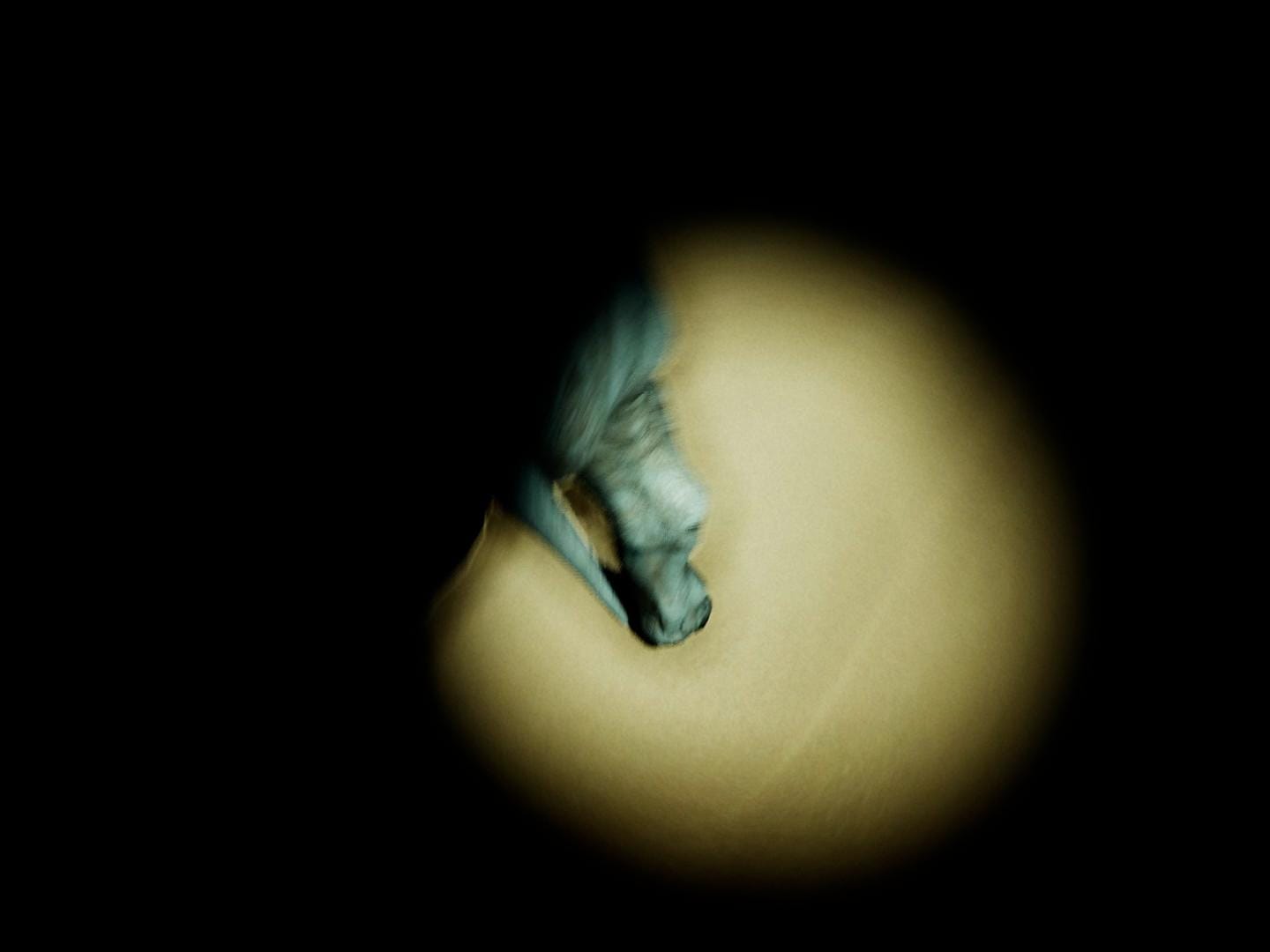

At the end of the game, you see this majestic horse emerge — this very spectral creature slowly approaching the player. I wanted to design a moment of magnificence, of magnificent beauty, where you wonder: what is this thing? What am I looking at? But then I immediately rip that away when you start watching it excrete into another container that you're catching. It moves from majestic to disturbing. That's how I play with relationships between objects.WARREN: The difference with Rube Goldberg machines as a reference is that you're typically presented with the entire thing first, then your attention is drawn to individual components. You're shown a scenario the machine solves, then focus on the components. But you've inverted this — because it's a cycle, on your first time through, you're presented with incomplete information about how this fits into the larger thing. It creates a destabilizing way to play. When will this end? You know the answer because you've seen the end at the beginning, but there's this tension of how each scene will connect to the next.

Games with mini-game components, WarioWare-style things, often aren't in service of a broader movement or idea. But thinking about these pigs — as people who eat things, or if you purchase something from a store, you're presented with the object, but the labor or material conditions of its creation are obscured intentionally. If you're able to reflect on both the thing and the process, maybe that creates a different relationship to the final object itself.

ROCA: That was definitely an idea I was trying to convey. WarioWare was actually a reference when thinking about this game — there's something fascinating about a game made up of tiny games. The way it plays with attention and player desire, where your goal is always changing. Just when you catch it, it changes to something else. In Slot Waste, I tried to design that catching part to be just long enough for you to get the hang of it, to get the timing right, before immediately being pulled into the next section.

I was thinking about this process of attunement that games can do — even larger-scale games like Elden Ring, where it takes time to memorize mechanics and finger movements until they become part of your processing. I wanted each section, or at least some of them, to have this constant remapping of your hand on the joystick. In the gallery, it's installed with an industrial joystick that I sourced from a vintage electronics store. It has this tension-filled feeling where it resists your movement, calling attention to the physical action. It was very important to me that there would be only one analog control without any buttons — everything based on your physical arm movement controlling the machine, constantly remapping how that movement is used in these different vignettes.

This interview was conducted on July 17th, 2024. It was heavily edited for style and content. You can see m