Shelter shows life as lovely, brutish, and short

A badger is surrounded by her children in their underground den.

I’ve heard plenty about of the brutality of nature via voiceovers from Attenborough and Herzog. Shelter starts without a single word, but, instead, an image. A badger is surrounded by her children in their underground den. They all run and circle around their mother—except one, who lies motionless. Before even taking control, Shelter establishes that, yes, you’re playing as a badger, but, no, this is not a whimsical Disney fable.

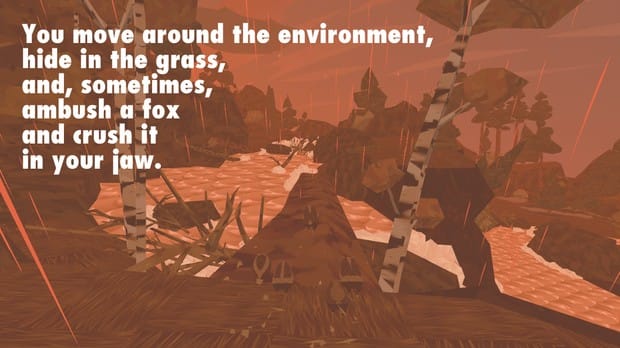

Once out of the den, you must hunt for food. Not for you; it’s for the children. The landscapes are abstract and geometric, all sharp angles and soft colours, like strolling through a Lawren Harris painting. You’re allowed to move around the environment, hide in the grass, and, sometimes, ambush a fox and crush it in your jaw. The pups, trailing you, stand around the body for a second, then start eating it like it’s the most natural thing in the world, which is apt, because it is.

There are no shortage of games about parenting. Bioshock Infinite, The Last of Us, and The Walking Dead are all critically lauded titles that have come out in the last year and are about fatherhood. Shelter strips out some of the baggage that comes with this dadification of games. There is no reinforcement of patriarchy here, no weirdly absent mothers. You play as the mother badger but the game strips any signifier of gender from her or the kids. Like the game’s scenery, it is an abstraction, less interested in nuance and more on the general anxiety of parenthood.

Like the game’s scenery, it is an abstraction, less interested in nuance and more on the general anxiety of parenthood.

Shelter does this by allowing something that other dad games wouldn’t dare: The pups can die. In my first playthrough one of the kids was lost to the darkness when I bolted in the wrong direction after hearing a loud noise. Two others were lost to a roaring river. There is a lot of danger in Shelter. Forest fires rage. Sometimes an eagle soars above, ready to snatch up one of your children. Hunger looms over everybody’s head. The game hits that note often, so much so that it doesn’t allow anything but protectiveness to blossom between me and the kids.

While the game’s artists are smart enough to differentiate the look of the pups, none of their behaviour suggests any personality. They are all interchangeable. Any parent I talk to can go on and on about the differences between their children, even from the start. They can tell you the way Janine never cried as a child, or how Sam spent weeks holding onto the wall while he learned to walk. The children in Shelter just follow and eat and die.

Some blame can be put onto the game’s length, which makes itself apparent with an abrupt, jarring ending, which barely feels like an ending at all. This is not to condemn short games—the length of Shelter isn’t as important as the fact that it feels like its a story half-told. This is the story about what a mother is willing to do for her kids, but a strong bond between me and the baby badgers never developed. The designers only hit that one emotional gong—your children are in danger!—loud and often.

I was haunting the game.

Shelter did find some poignancy, though it seemed accidental. The first time I played, all the pups died. I was alone, walking through a barren autumnal plain. The mother never needs to eat, so I just kept pushing forward. I was a ghost, haunting the game. There was no game over screen, just a stubborn refusal of the game to end, or of the badger to give up. As a portrait of parenthood it feels lightweight and one-note. Shelter fails to say much about having kids, but in a small way, it does say something about losing them.