Shenmue and the rise of lonelycore games

Shenmue debuted on the Dreamcast in 1999. Its sequel, the aptly titled Shenmue II, dropped in 2001. Like most videogames, their narratives ain’t Shakespeare. The first game focuses on Ryo Hazuki avenging his father’s death and investigating a bizarre mirror. Spoiler alert: Shenmue II has Ryo looking at other mirrors and continuing to investigate his father’s death.

Hey, he isn’t a great detective. But the games have persisted in the public mind. Creator Yu Suzuki gave a postmortem on it at GDC this March. These types of postmortems pop up at the Game Developers Conference steadily each year. They tend to be titles who, it is understood, are relics of the past, that the creators can finally kick back and soberly discuss. But they are presented curios. Larks. Nostalgia.

By way of context: Zork also had a postmortem this year.

Why are we starting to hear more about Shenmue now?

Zork came out in 1980, nearly 20 years before Shenmue. I’m not an expert on Zork, nor am I an expert on Shenmue. I think Zork’s place in games has been fairly well articulated and accepted as a truth: It helped popularize interactive fiction. Interactive fiction is a term floated around Heavy Rain (the first trophy you earn thanks you “for supporting interactive fiction”), but it didn’t invent it.

So why does Shenmue matter today? Why are we starting to hear more about Shenmue now? If Heavy Rain didn’t invent interactive fiction, then what could Shemue possibly have ushered into gaming’s lexicon?

The answer isn’t that simple.

Shenmue created the open-world genre as we know it today. It got there before GTA3, for better or worse, setting the tone, direction, and intention behind every game that has rallied behind the open-world tag. I say for better or worse because I have never really felt like any open-world game has accurately captured the feeling of being in any world, much less ours. It’s this unrealness that is Shenmue’s triumph.

A Guardian piece from earlier this year highlights Shenmue as being “charmingly Japanese,” with its protagonist being:

always respectful of his elders… grateful for the allowance he receives each day; his tidiness with empty drinks cans and toy capsules; how he takes off his shoes when he gets home – is quite unlike 21st-century game protagonists. But just like any GTA series antihero, he does insist on sleeping in his jeans. They are nice jeans, though, as the denim specialist in the commercial hub of Dobuita is happy to tell you. Just don’t ask him about his experiences with Asia Travel Co. In fact no one you speak to had has a good experience with the Asia Travel Co. It is a credit to the intricacy of this world that it contains a dubious travel agency.

And whereas The Guardian focuses more on Suzuki considering turning to Kickstarter for Shenmue 3, and touching very lightly on the games’ conversational awkwardness (Ryo is super-clumsy around the ladies), The Guardian flies a stealth bomber in the preceding graf past Shenmue’s importance.

Whereas The Guardian focuses on the series’ apparent realism (indeed, it was among the first games to have product placement), what it misses is that this is exactly where the cracks in the open-world genre first start to show.

Ryo is a fucking cartoon character. And so is his world. For a man who lost his father in a world that is supposed to ring true and familiar, he carries himself with a neutered unfeelingness more appropriate for a disaffected teenager than a grown man seeking revenge and taking the law into his own hands. His pain is an excuse for a familiar trajectory no different than that in River City Ransom or Streets of Rage. Only in this world, it would be ridiculous to punch a trashcan and find a hamburger. In Shenmue, you punch a clock and can buy a hamburger—but only if you want to! If it comes close to capturing our world, then this is it.

People have criticized open-world descendants like Skyrim or Fallout 3 as perhaps being too unfocused or narratively flimsy to hold anyone’s attention for more than a couple hours once you get acclimated to their core mechanics and quirks (V.A.T.S., for example). It’s a divisive point the genre has yet to rectify; Gus Mastrapa once wrote a piece for this very publication in 2011, Things I Ate In Skyrim, that speaks to how tofu-soft and malleable games have become. That is, you can play Skyrim for hours on end without fighting a single battle, nor crossing paths with a single dragon, and just wander around and eat shit. And nobody can ever say you haven’t experienced what Skyrim intended for you to experience. They put it there, you did it, so that must be what you’re supposed to do.

Shenmue is to blame for these misshapen, rambling games.

Think back to that cheeseburger you could buy. These open worlds have freedom insomuch as you have freedom in a grocery store: You can buy whatever you like, but only if you pick among whatever the vendors and store think you should be able to buy there.

That isn’t freedom. That’s the illusion of choice.

Whether you buy the illusion, I think, boils down to what type of player you are. You might be the type of person who rises through the ranks, and plays all the missions. Goes to each NPC, builds relationships, unlocks garages. You want to buy the ride.

Then are people who, the moment they are granted freedom to do as they wish, look for ways to break the illusion. They want to see how far out they can swim before the world “stops” them. They want to jump off tall buildings and see whether they survive. They want to kick the tires.

The relationships you build in these worlds are ultimately hollow and shallow.

It likely will not shock you to learn I am the latter, and feel lonelier in open-world games for it. But then, just like the cuisine in Skyrim, who is anyone to say which approach is “wrong?” They put it there, so this is what I should be doing.

That said, even the biggest open-world apologist would likely concede the relationships you build in these worlds are ultimately hollow and shallow. They are false, so how can anything else in the world be true?

So what, then, are open-world games really all about?

I turn to Suzuki and his recent Shenmue postmortem for the start of an explanation. It was “the first time ever” the creator discussed the, er, creation of Shenmue.

Among the many, many things Suzuki covers in his hour-long talk are the challenges he had to face in creating the world’s first open-world game. That wasn’t his team’s intention.

Suzuki had humbler intentions. In fact, he wanted to do something semi-derivative: To make a Virtua Fighter RPG. The game was initially imagined as “Virtua Fighter RPG: Akira’s Story.”

But something funny happened on the way to the NeoGaf forum: Suzuki got more and more ambitious. Many times throughout Suzuki’s talk at GDC, his translator quotes him as saying “this is now standard in the open-world genre.” But at the time, it wasn’t. At the time, it was a ton of fucking work that nobody had done before.

Case in point: Shenmue takes place in Kanagawa Prefecture’s Yosuka in 1986. So, Suzuki being Suzuki, and wanting to make an authentic open-world game, he and his team accumulated real weather information from a three-year pattern for the game’s simulation. After all, it would be audacious to plop players down in that world and flub some details. It’d be sloppy or irresponsible. This is what Suzuki seems to be implying.

From a design perspective, it makes sense. But this doesn’t account for creative license. Why, for example, in Louie, his wife after their divorce is black; before it she is white. It is never acknowledged in the world, but makes the world more interesting. But gaming and tech are obsessed with the uncanny valley—there is an implied aspiration to capture what we already have. Trying so hard to be real in a simulation just adds up to falseness.

This is one of many layers the game has at its core building to an overall falseness, and intentional simulation of the real world. Rather than just have the weather be randomly thrown at you, Suzuki saw fit to have the weather be recreated from the time in which the game was set.

///

In Mad Men this past season, an IBM 360 arrives at the office. Computers, it is promised, will revolutionize the way business is done and the way we live our lives. The ad agency is sold this line: “The IBM 360 can count more stars in a day than any man can count in a lifetime.”

Don Draper, everyone’s favorite womanizing philosopher and deadbeat dad, elicits this flowery sentiment: “What man laid on his back and thought of a number?” Well, everyone in Shenmue’s Kanagawa Prefecture: Suzuki says the rain and snow in the game were algorithmically generated.

Computers, technology, and game design are tools that can work in harmony together to make our lives better. It isn’t an either/or proposition. We have long known you can use games to make statements and challenge people’s opinions on things, but when, unquestioningly, open-world games set out to make a 1:1 facsimile, something far more false is ushered forth.

What I mainly remember about Shenmue, and especially its sequel on the Xbox, is how hollow everything in the world feels. If you’ve played the Yakuza series—an arguably more successful version of the same ideas here—you know what I’m referring to.

Wandering around in Yakuza is much like wandering around in Shenmue. That is, you are a badass Japanese gangster-type. You walk around a realistic-seeming city with a worthy cause (in Shenmue you avenge your papa’s murder; in Yakuza you wander around fictionalized versions of real Japanese cities and do noble shit like try to save orphanages). Like in Skyrim, you can never even touch the main game, just eating shit as you go. People stop and pick fights with you. When you pump the brakes and engage the locals in conversation, they do little more than bark clipped, awkward sentences.

Consider this randomly quoted dialog I found off YouTube from the original game, totally representative of the level of discourse you’ll find in Shenmue. Bear in mind, all conversations have a scratchy quality to the audio.

Ryo happens upon a young boy on the street.

RYO

Hi.

BOY

Hey mister! Let’s play baseball!

RYO

Some other time, okay?

END SCENE

This sounds like an awful improv scene in a level-one class. The teacher will clap enthusiastically, obviously covering for the fact it was intensely awkward, bark a couple words of encouragement (“great commitment!”), and nobody really learns anything after it.

So what just happened?

What just happened is the player is told a lie, and the audience went along with it. It got a pass at the time because it was a novelty, but over time it’s become a watershed moment in our culture’s exploration of the uncanny valley.

The fantasy doesn’t believe, so the audience doesn’t either.

These little moments remind us that we’re in a game. In game design terms, its “flow” is broken. If Shenmue is meant to reflect the world back to us and it presents interactions such as these, it can’t help but break the fantasy and make me aware I’m just playing a videogame in a room with friends or alone at night as my cat sleeps. The only other analogue I can offer is when you’re watching a movie and an actor is so out of their depth that you realize they’re an actor playing a part. (A clunky example would be Rihanna as a systems analyst in Battleship) The fantasy doesn’t believe, so the audience doesn’t either.

Most of us rarely talk to strangers, but in Shenmue, it is the most natural thing in this fake world. In so doing it is perhaps the first game to highlight how isolated you can feel in a crowd.

This may, again, boil down to what type of player I am. So your mileage may vary. But for me, open-world games are not vast playgrounds where I can be king. They are vast playgrounds of errands for people I could care less for, escort missions with destinations that mean nothing to me, and a set of problems I can’t relate to.

Shenmue had the script flipped from where things are today in the genre, with a heavier emphasis on minuatie. On these conversations with little boys. On you taking jobs driving forklifts. There were no strip clubs with gyrating bits of pixels clumsily asserting “this is an adult game.” Shenmue treated you like an adult by, in some respects, dropping you in an alienating world and letting you find your way. That was an accident. And it’s the part of Shenmue that’s often ignored in games hearkening back to it today.

///

Many conventions modern, expansive open-world games share are, ironically, due to the data restrictions Shenmue faced on the Dreamcast.

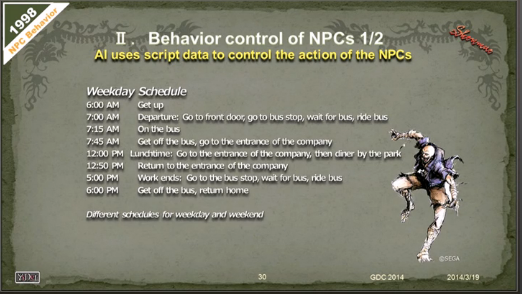

At GDC, Suzuki talked about the need to control NPC behavior so the city felt alive. Behind him, a slide explains that “AI uses script data to control the action of the NPCs.” It reads like something straight out of “Fitter Happier.”

The AI behavior needed to be predictable so they weren’t doing random things at random times. So they adhered to a “normal” schedule. It was two birds with one stone, scripted to simultaneously get hit with a carefully coded pebble.

It’s meant to make the world feel more real, but instead it makes it feel much more robotic. What would have made the world much more interesting—and this is a huge comment on who we really are as computers understand us—is, and I’m paraphrasing here, when Suzuki says: “We gave all the NPCs free will. Then a bug cropped up.”

That bug? Everyone in the entire town was gone. Nobody was showing up to work.

They hadn’t disappeared. They were all just in the convenience store, stuffing their fat fucking digital faces. Literally, Suzuki says, they could not leave because there were so many people in there.

Suzuki said they had to put something in the code to regulate how many people could be in a restaurant or convenience store at any one time. They had to widen the doors.

This bug, had it not been fixed, could have been the key to making for more lifelike simulations in open-world games. Or at least their inhabitants.

Who among us would go to work everyday when we could just pig out from 9 ‘til 5 without any repercussions?

This bug, had it not been fixed, could have been the key to making for more lifelike simulations.

That, too, would be false, but at least it would be a metaphor, or a window, into seeing what the world would be like if we all acted based on our impulses. What an interesting open-world environment to be in a game—if everybody was Niko, instead of just you.

///

Shenmue often gets mentioned in the same breath as Zelda because, like Link, Ryo is the one who enters someone’s house and smashes their pots.

Again, my mind turns to improv—the theatrical simulation of our daily lives. In improv comedy, there’s something called “the game of the scene.” It is hugely popular in New York, and Upright Citizens’ Brigade was at one time synonymous with it. The fact that so many people have been plucked from UCB to be on TV and movies more so than anyone out of Chicago in recent history, I think, speaks to how powerful this notion is. Chicago acknowledges the existence of this philosophy, but focuses instead on other things like the relationship being explored in a given scene.

The “game of the scene” is all about honoring whatever the first weird or unexpected thing is that happens in a scene. In a restaurant scene, if the waiter comes in and accidentally smashes a plate, what should follow next is another waiter coming in and breaking two plates. And so on and so on.

The Chicago-style version of the scene would have the first plate smash and create some awkward tension between the couple having dinner. The relationship would play out, they’d realize something about how important they are to one another. Then, at the end, another plate would break.

Neither represent reality, truly, but a more interesting version worth plunking down in front of an audience to get engaged and engrossed.

But they’re both false, and you need both to make for an interesting world. Somehow, in entertainment, we have come to expect a compartmentalization of our own worlds being spat back at us. More than that, we accept it without question.

In any open-world game, you can never truly join the world around you. You are an outsider having adventures. Everyone else is just having their pots smashed. Their fathers haven’t been murdered; they just want to play baseball.

You can play Skyrim, never touch the main story, and just go on an eating tour around the world. You can never get inducted into a secret society of vampires, never forge a single shield. You can just eat.

In Grand Theft Auto, you can kill a couple people, get chased by the cops, and call it a day. Your actions don’t really have any consequence, your avatar doesn’t really belong in that world anyway, and so you feel all the lonelier for it.

In Shenmue, 11 years prior, you can reconcile the death of your father not through investigation but by driving a forklift or playing pachinko all day. It’s not like your dad’s gonna get un-murdered any time soon.

But the more Suzuki talks, the more it becomes obvious that the rise of games centering on isolating experiences and worlds that care little for what you do in them can be traced back to Shenmue.

I play games the way I do because I want games to serve as a respite from day-to-day life. I’ve never cared for Animal Crossing because I already live in a town. There’s a certain fantasy in the sense I’ve never talked to my real-world neighbors — either here in Los Angeles or back when I was living in Chicago. But conversations alone aren’t enticing enough for me to stick with a game. I talk to people all the time.

I’ve never cared much for Rock Band because I know how to play a guitar. Mashing colored buttons in proper time can’t hold my interest because I’d rather mash on frets and make some real noise.

What we choose to do in that empty space is up to us and us alone.

The people who play games otherwise—who yearn to play Blackjack in in Fable or Red Dead Redemption—are seeking something else. I’ll leave it for them to say what.

Games are a Rorschach test: They’re exercises in loneliness. What we choose to do in that empty space is up to us and us alone. Shenmue unwittingly understood this better than any game before or since.