Silent Hill 2’s endings aren’t what you want, but what you deserve

In the summer of 2010, I had a few weeks off between the end of another graduate school semester and the start of my first clinical placement, and was looking for a way to unwind. Naturally, I decided to replay the entire Silent Hill catalogue back-to-back.

The series’ first entry had not aged well in many ways, but having not played it in years the nostalgia was palpable for me. I enjoyed traversing those familiar streets with terrible draw distances, battling the preposterously low-poly lizard in the school basement, letting the stilted voice acting wash over me. There was a predictability to the horror that made it almost comforting to play. I found Kaufmann’s glass vial. I used the “unknown liquid” to save Cybil. I saw the Good+ ending, as I knew I would. On to the next.

When I loaded up Silent Hill 2, I felt a surprising unease. I might have even gone so far as to call the sensation that of dread. I remembered from my past experiences with the game that it would not be so predictable, so easy to control as its forebear. This was because Silent Hill 2 employs a curious and inscrutable mechanic in which the way one behaves in the game world subtly aggregates to determine the ending. The clear-cut binary choices that I enjoyed when replaying the first game were gone. In Silent Hill, if I used the unknown liquid, Cybil lived and I saw a “plus” ending. Otherwise, she died and I saw a “minus” ending. End of story. I knew exactly what I was going to get ahead of time, and I had total control over the outcome. It didn’t matter how I treated Cybil throughout the game, or how I really felt about her deep down in the inky black of my unconscious. In Silent Hill 2? I wasn’t so sure.

When I loaded up Silent Hill 2, I felt a surprising unease.

Slowly walking down the gravel path toward the graveyard at the start of the game, I began to feel nervous to the point of paralysis, as though the game itself were watching me. What did it mean if I looked at Mary’s photo more than once? Weren’t there certain scenes or messages that, if viewed, would steer me toward one ending or another? The ambiguity was overwhelming. I couldn’t help myself: I looked up a walkthrough to remind myself of the three main endings, how to get them, and plan my playthrough accordingly.

The “Leave” ending I knew I had seen at least twice before—it was more-or-less the good ending, in which protagonist James Sunderland atones for his actions. The ending called “Maria” also sounded familiar; I had vague recollections of following an online guide—perhaps the very one I was consulting now—to bring myself to that conclusion.

Third was the “In Water” ending. I read the description; I had certainly never seen it. This seemed absurd, as I considered myself a Silent Hill 2 super-fan: I had gone through the trouble of finding the bonus ending “Rebirth” and the bizarre joke ending known as “Dog,” I had posted story interpretations on message boards as a teenager. I even dressed as James for Halloween one year, complete with flashlight and wooden plank. How could I have never seen “In Water”? I started to read the walkthrough’s description of how to achieve it: “Examine Angela’s knife often.” Easy enough. “Read the diary on the hospital roof.” No problem. “Stay at low health throughout the game.” Oh, right …

I closed the walkthrough, played through the game, and saw “Leave” for the third time.

///

A major goal in psychoanalytic psychotherapy is to strike a balance between agency (i.e., taking control) and acceptance (i.e., surrendering control). Teetering to the extreme on either end of the spectrum can be problematic. On one hand, forsaking all sense of control restricts us to a passive and dependent position, the feeling that we are being dragged along through life rather than actually living it. Conversely, an inability to accept things outside of our control can lead to rigidity and difficulty coping when something inevitably happens that could not have been foreseen or prevented. Acknowledging that we are in charge of ourselves but not in charge of everything that affects us is a deceptively sophisticated psychological and spiritual achievement that most of us work on for our entire lives.

Strike a balance between agency and acceptance.

Videogames explore this dialectic quite naturally, often without even trying. Because games are driven by player input but also bounded by programming, there is an inherent push-pull between agency and acceptance. Some works, like The Stanley Parable and the original BioShock, deliberately draw our attention to the fact that our ability to affect what happens in the game is merely an illusion. Other titles, especially massive sandbox games like Skyrim, try hard to uphold the notion that we control everything; by advocating the notion that we can go anywhere and do anything, such games try to convince us that we are the sole arbiters of the gameplay experience.

Of course, the idea that total immersion in a virtual world is akin to having total control over it is very different from our experience of real life—there are always things we cannot predict, or things we do for reasons we cannot consciously explain. Silent Hill 2 boldly attempts to capture this complexity in its story, imagery, and above all its ending-determination mechanic, which seems as strange and ahead of its time today as it did when the game was first released in 2001.

From a plot perspective, Silent Hill 2 opens by presenting James (and therefore us vicariously) as a fierce rejector of acceptance. He has come to Silent Hill looking for his dead wife Mary, who has apparently written a letter telling James to find her there. James puts his life and sanity at risk rather than acknowledge the impossibility of his situation and accept that Mary is gone. James and the other mournful denizens who wander listlessly about are desperate for meaning, closure, and a sense of agency. They seek to regain control over their lives, which have spun out of control following various traumas and misdeeds that link them to the town. Yet their experiences in town repeatedly suggest that some things—even their own thoughts and feelings—are outside of their conscious control. Silent Hill is a test: the town morphs itself to match the inner struggles and secret wishes of those who walk its treacherous streets. The question is whether James will be doomed to repeat his mistakes by believing he controls everything, or be consumed by the agonizing notion that he controls nothing. Or—perhaps—he might find a place to exist in between.

The ending mechanic adds another layer to this exploration of control versus surrender by directly involving our actions as players. The game tracks diverse and often incidental aspects of play behavior, such as how many times we look at a letter in our inventory, whether we physically strike another character, or whether or not we wait around to hear the end of a monologue before leaving the room. Most importantly, we are not explicitly told which actions contribute to which ending, if any ending at all. Unlike in most games with multiple endings, including the first Silent Hill, we are not presented with clear forks in the road that delineate one path from another. The game instead presents a world in which our actions have tremendous weight, while simultaneously leaving us blind to how those actions will radiate out and impact the course of events. Silent Hill 2 determines not the ending we are trying to achieve but the one that corresponds to how we played the game, whether we want it or not. We are active agents within the game world, but at the same time must accept that sometimes things just happen, and sometimes we just are who we are.

Silent Hill 2 is terrifying because it recalls the nausea of daily life.

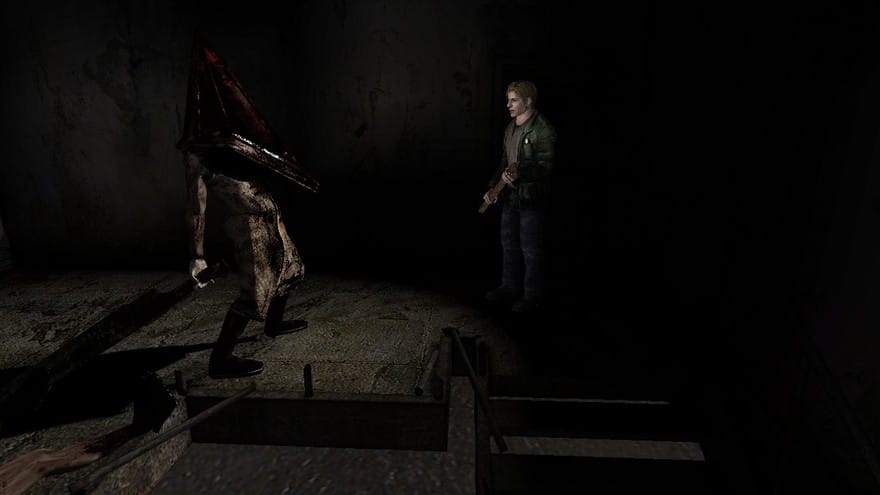

This generates a unique and at times delirious anxiety during play, well suited to the game’s genre. But it is not the grotesqueries of Pyramid Head that unsettles in this case—it is that this arrangement feels disturbingly familiar. Silent Hill 2 refuses to indulge our desire for omnipotence, for carefully planning out each step to willfully steer what happens to us and the broader story. Instead, we make decisions that we think we understand, which may or may not matter, and that yield outcomes at once logical and wholly opaque. Along with James, we experience the tug-of-war between a desire for control and a fear of responsibility, a craving for submission and a disgust for dependence. Silent Hill 2 is terrifying because it recalls the nausea of daily life.

///

So—why have I still never seen the “In Water” ending? No matter how familiar I am with Silent Hill 2’s deformed monsters and dark hallways, I will always find it too nerve-wracking to wander the town’s fog-ridden streets at low health. To do so would be, we might say, against my nature. In some ways, this is the game’s ultimate comment on the tightrope walk between agency and acceptance: we are prisoners of our own natures.

As James progresses through his Silent Hill fever-dream, periodic encounters with the other lost souls reveal the troubling pattern that they are making the same mistakes that drew them back to town in the first place. Eddie’s rage and paranoia overwhelm him once again. Angela cannot break free of her traumatic past and is ultimately consumed by it. But James … the one I, the player, control … he can change, can’t he? But perhaps the real question is, can I? My agency is not only constrained by the game’s programming, but by my own conscience, my resolve, my compassion. No one is stopping me from seeing “In Water” but myself.

So, at last, I gave in. I YouTubed it. It seems to me to be the ending of pathological acceptance: after spending the game recklessly running around close to death, the game assumes that James (but really us, since we made him do it) has essentially put himself at the mercy at whatever god or demon pulls the strings in Silent Hill. This can end nowhere but in the ultimate surrender of death.

Silent Hill wants us to thread the needle and find a certain equilibrium.

This starkly contrasts the “Maria” ending, which represents agency taken to its extreme. In this playthrough James has worked meticulously to sculpt a relationship with Mary’s doppleganger—whose realness is always in question—pushing aside any acceptance of the loss of his wife in the interest of recreating what he once had with her. He succeeds, but only to doom himself to relive it all again, as the final cutscene suggests that Maria suffers the same sickness that ultimately drove James to murder Mary.

“Leave” may be the closest James can come to finding the balance between these two points. And it makes sense that this is the easiest ending for us to achieve as players. For all its perversity, Silent Hill wants us to thread the needle and find a certain equilibrium, fragile as it may be. Suicide is shocking but final; repeating the past is gloomy but predictable. Moving forward into the unknown, however—taking ownership of our lives while maintaining reverence for that which we do not know and cannot change—that is truly scary.