Goichi Suda, or Suda 51 as he is often known, can be a hard person to pin down. His work, especially in recent years, has been accepted into videogame culture as “crazy” or “weird,” identified as flippant stories filled with self-referential non-sequiturs and mulched manga plotlines. “Oh it’s just crazy old Suda,” seems to be the standard response to his work, and you can drown in articles that introduce him as “the Tarantino of games.”

This is a side effect of his breakthrough game perhaps, the otaku assassin simulator No More Heroes (2007), which cemented him as a master of the perverse and the throwaway, its breathless pop-culture mutations driving home the idea of a Suda as a colorful clownish persona. It’s a persona that Suda has himself propagated in recent years, seeming to respond to the popularity of No More Heroes by trying to bring the same barrage of colorful, perverse, brash ugliness to games like Lollipop Chainsaw (2012) and Shadows of the Damned (2011). For those who were introduced to Suda with No More Heroes and the sneering Travis Touchdown, this progression might seem logical, but for those of us who caught him earlier in his career, things look altogether different.

“an environment that let me create everything I wanted to create”

“Kill the past.” It’s a phrase that, to fans of Suda’s work before No More Heroes, will be intimately familiar. The loose title for the trilogy of works he produced after founding his studio Grasshopper Manufacture, namely The Silver Case (1999), Flower Sun Rain (2001) and Killer7 (2005)—it suggests violence, regret, and the pervading presence of memory. The first of these, The Silver Case, has never been released outside of Japan, that is, until this year. Quietly announced back in May, Suda himself is directing a remaster and English translation for release this fall. Recently appearing at Bitsummit in Kyoto, Suda demonstrated the game in video form, showing it for the first time with English dialogue. This makes it the final chapter in a process of localization that has taken almost two decades.

{"@context":"http:\/\/schema.org\/","@id":"https:\/\/killscreen.com\/previously\/articles\/silver-case-hd-completes-17-year-localization-iconic-videogame-trilogy\/#arve-youtube-xqsxy6y6reo","type":"VideoObject","embedURL":"https:\/\/www.youtube-nocookie.com\/embed\/XqSxy6y6rEo?feature=oembed&iv_load_policy=3&modestbranding=1&rel=0&autohide=1&playsinline=0&autoplay=0"}

The Suda 51 of “Kill the Past” is a different Suda than that of his late, Western-oriented games. It’s perhaps important to note that No More Heroes was, in fact, the last game Suda directed, choosing instead to take on overseeing roles such as creative or executive director since then. In a recent interview he even told Kill Screen that currently he “has a lot of input” but “doesn’t really see [himself] as a lead or artistic kind of director,” preferring to set up the scenario for a game and its team, rather than painstakingly manage every detail. The Suda of the “Kill the Past” era was a very different beast. In 2015’s The Art of Grasshopper Manufacture, he talks about how, encouraged and guided by Shinji Mikami, he made Killer7 “practically with my own hands.” He adds that Mikami “provided an environment that let me create everything I wanted to create. That kind of development is rather rare. I haven’t had an experience like that since.” This approach is what marks out those games from the rest of his body of work.

As said, The Silver Case is the last remaining game of that era to make it to the West. And with Suda now no longer closely directing his games, and the Western market dictating a change in his approach, it represents what might be the last great Suda 51 game. Speaking again in The Art of Grasshopper Manufacture he explains how it was inspired by Jean Luc Goddard’s experimental cinema: “Godard challenged the use of visual and audio multi-expression techniques. I wanted to make a game that did the same: something that can’t be deciphered in just a single glance.” For Suda this was a struggle, especially in the late 90s. This was, in Suda’s words, “a time that many people decided ‘video games are justs for kid after all.’” He wanted “No rules on the breadth of expression” integrating illustration, 3D models, live video, photography, and typography. But this brought him up against filmmakers and technicians that didn’t share his vision. “People made fun of the game. They felt ‘you can’t take pictures that don’t connect from beginning to end,’ and they wouldn’t start the camera.” It was “a battle,” but the result was something that, despite everything, Suda ranks among his best work. “I really wanted to go down the path of making a game in a way that no one had ever achieved before. The Silver Case is like the history of that battle.”

Suda seems to have delighted in frustrating the player

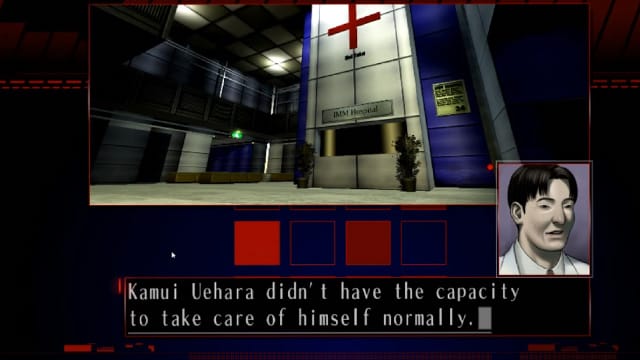

What is The Silver Case then? I suppose we might call it a visual novel, but like the games that would follow it—the looping adventure puzzler Flower Sun Rain, and the hard-boiled surrealist shooter Killer7—genre feels like a reductive way to describe it. It is, in the simplest sense, a piece of twisting, ornate interactive fiction, one that changes its presentation style at an alarming rate, and shifts between geopolitical machinations and oddball dialogue without warning. The same might be said of those other two entries in the “Kill the Past” trilogy, a trilogy that perhaps is better thought of not as a series, but as an analog to Park Chan Wook’s Vengeance trilogy, or Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy, as being an exploration of themes, a process of experimentation, and a method by which each director might hone their craft.

Like those, and other great artistic series, “Kill the Past” is powerful because it represents an exploration of an artist’s own identity, and, like many do, culminates in their greatest work: in this case, Killer7. But while Killer7 might be Suda’s own “proudest moment” it lies incomplete without the games that birthed it. Flower Sun Rain received its English localization in an unlikely DS port (subtitled Murder and Mystery in Paradise) in 2008. One which is still well worth searching out for it’s Groundhog Day (1993) structure and entirely numerical puzzle design. The Silver Case was supposed to follow, but it disappeared, perhaps after low sales and the poor critical reception of Flower Sun Rain. Eight years later and The Silver Case is finally getting the same treatment, though whether its reception will be equally frosty is hard to judge. These are difficult games, conceptually ornate, and unfriendly towards those looking for answers. Suda seems to have delighted in frustrating the player, perhaps in the same way as his favorite writer, Franz Kafka, who in The Castle (1926) entwined the reader in a plot that goes nowhere, on a mission of decreasing importance, within a cast of characters prone to distraction.

This frustration, obscurity, challenge and otherness is also what makes the “Kill the Past” games so enticing. Unlike Suda’s easy-to-please late work, that seemed desperate to break the Western market at any cost, here were a set of works that dared to be overtly serious, impregnable and unfriendly. Perhaps it is appropriate that their process of localization has been as ornate and bizarre as their narratives, it suggests that, even after two decades, these masterpieces might still have some secrets left to offer.

The Silver Case HD is due to arrive for PC this fall.