The makers of Super Mario RPG and No More Heroes are making a tiny mobile game

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel.

Million Onion Hotel has the kind of kooky, kawaii originality you can only grub up in Japan. Certain to fill your daily allowance of whimsy in one serving, the hyper-cheerful mobile game features an ensemble of cute magical onions and parading livestock. It is more than a zany mobile app, though. These stampeding cattle and soaring asparaguses are leading the charge in a cultural shift that may change how Japanese games are made.

Outside of Japan, there has been a cloudburst in recent years of small, startup game studios creating big, important titles—for instance, the Fullbright Company’s Gone Home, and, of course, Minecraft. But this sea change has been slow going in Japan. Here in the West, it isn’t that uncommon for one person working on a shoestring budget from her bedroom to produce a work that can hold its own with a giant production. But across the Pacific, in the motherland of monolithic game publishers like Nintendo and Sony, the concept remains foreign—although the tide has started to turn.

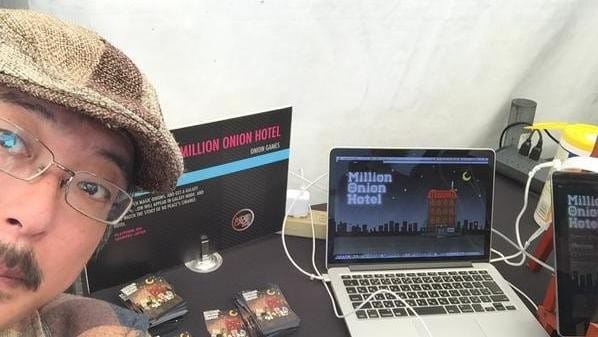

For proof, look no further than Million Onion Hotel’s three-man team, Onion Games. The team’s resumes contains some of the most imaginative games ever made. Yoshiro Kimura, their director, is something of a cult figure among cognoscente of off-center videogames, with a body of work that includes cult classics (Rule of Rose), holy grails that never made it out of Japan (MOON: Remix RPG Adventure), and the closest games come to grindhouse cinema (No More Heroes, Shadows of the Damned). Those stripes alone establish him as a significant designer, if not a best-selling one. His two partners at the studio share credits on classics like Little King’s Story and Super Mario RPG.

Unlike the fresh-faced millennials who form the majority of small independent studios, Kimura’s hair is stippled with gray. So why is an old hand with big games under his belt striking out on his own? One reason is because he’s adventurous. “I am not only a game designer, but also a traveler on this planet,” he said over email. The other reason is more sobering. Lately, Kimura has felt increasingly dissociated from an industry he’s been a part of for the past 20 years. “I remember I almost gave up making games. I was escaping from the Japanese video game industry and the people,” he said. “I felt there was no place for me.”

The problem, in Kimura’s opinion, is that Japanese games as a whole have sacrificed their weirdness and experimental vibe in service of the mighty dollar (or yen, as it were). “There was a place for making strange games a long, long time ago. But something changed—something became stronger than before. You know, a big company has to earn a lot,” he says, explaining how the mounting pressures of the corporate lifestyle eventually sucked the joy right out of his livelihood, which in the past has included drawing dungeon maps, animating clay puppets, and personally humming the sighs and lovelorn expressions of wistful little peasant-minions.

Here in the West, quitting your day job to become your own boss and chase a dream is basically something everyone fantasizes about. But Japanese culture doesn’t necessarily share our enthusiasm for individuality, which helps explain why the small number of independent game studios in Japan lag behind their Western counterparts. “The Japanese mentality is very reserved, and they prefer to let their work speak for itself, rather than seek the spotlight. In short, they’re much more introverted, and that lack of ‘outgoingness’ is one of the things we weren’t sure about,” says James Mielke, the founder of BitSummit, Japan’s fledgling powwow for independent creators. “None of us—the organizers, the guest speakers, the sponsors—had any idea of what to expect.” Despite the uncertainty, the first two events have been a big success, swelling to over 5000 participants.

This sea change has been slow going in Japan—but the tide has started to turn.

Last March, at the second annual event, Kimura was a guest of honor, and he attended wearing an onion hat. A few years prior, he hadn’t thought it possible to be in that situation, surrounded by a crowd of free-spirit game creators—not in Kyoto. But on a business trip to San Francisco, in 2012, he encountered a flurry of bright and wonderfully creative games—games like Fez and Spelunky and Antichamber—that reminded him of the games he made many years ago, before the Japanese game industry became so, well, industrious. “It moved me very much,” he said, describing it the way you would a spiritual experience. “Teardrops were coming from my eyes, like I was seeing beautiful nature, the beautiful sky, the beautiful animals, beautiful mountains. I thought I might make my original world again in this wild nature.”

Shinjuku header via Morio.