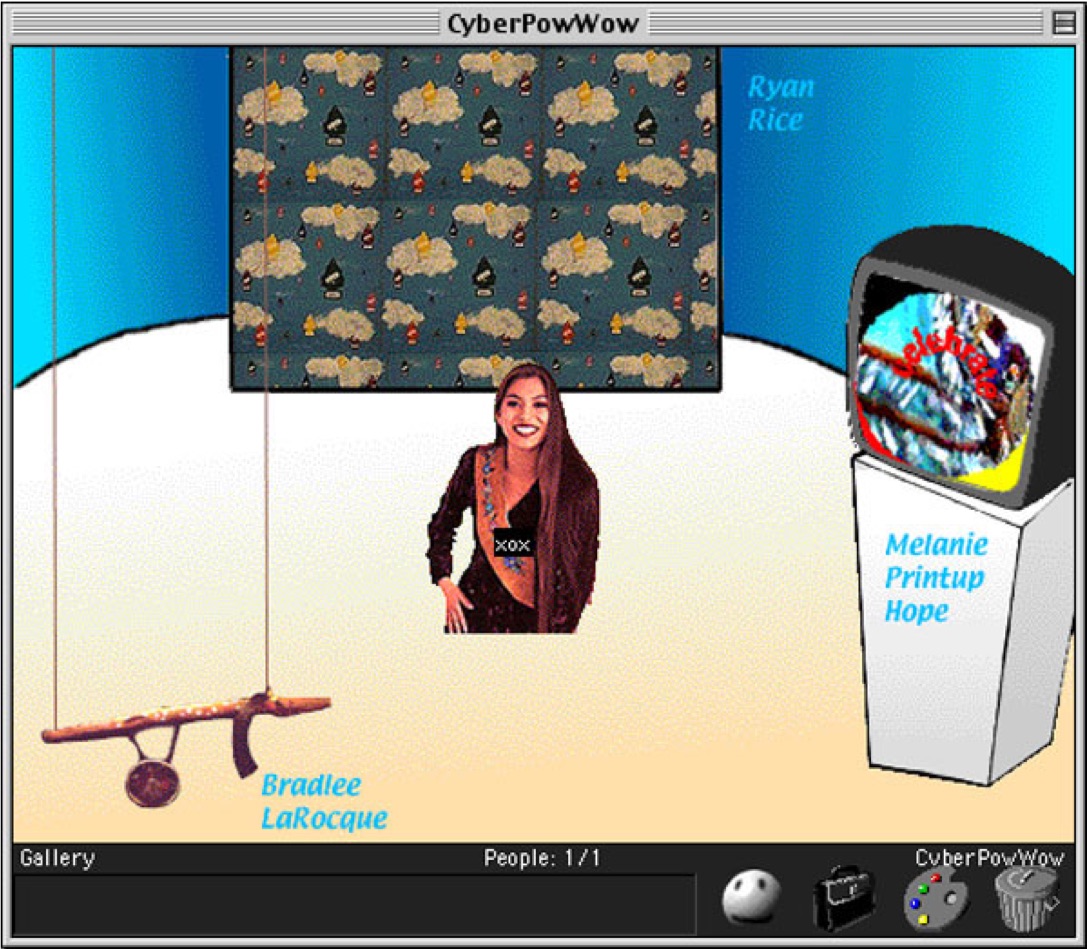

In 1996, Skawennati logged on to create CyberPowWow, an Indigenously-determined chatroom and gallery. In the years that have passed, the artist has forged virtual communities through her projects that compound Native histories and imagined futures—notably, through her machinima series TimeTraveller™, created entirely within Second Life. Born in Kahnawà:ke Mohawk Territory, Skawennati belongs to the Turtle clan. She holds a BFA from Concordia University. Together with her partner, artist and educator Jason Edward Lewis, Skawennati directs Aboriginal Territories in Cyberspace (AbTeC), a research network and educational program made up of artists, academics, technologists, and activists—its goal to ensure that Indigenous people are present in cyberspace. “We would like to also affect the look and feel of cyberspace…to not just be in it, but also shape it into our own image,” the Montreal-based artist tells us.

We were honored to speak with Skawennati on the cinematic worlds she’s created in Second Life, the biases cultural embedded in the program, and nation-building through art and education.

Do you remember your first creative impulse?

I was born in Kahnawà:ke, my reserve and Mohawk territory, which is close to Montreal. where I currently live. I was a very creative young kid. My earliest memory is putting beads on a needle. My great aunt taught me that. I loved staying at her house. Her daughter, Kathleen, was also an artist. She is the person I feel who taught me that I could make anything I wanted. Together, we made dolls’ clothes—little beaded samples and embroidery too.

My mom would say to me, “You can be whatever you want.” I remember I wanted to be a ballerina dancer. I love my father—he did not think that a kid with such good marks should become an artist who will be poor when I could be anything I wanted to be. He said I could be a doctor or a lawyer. I think I only realized I could be an artist in my twenties.

How did your educational experience shape your creative practice?

I initially studied pure and applied science. I was getting terrible marks, and it was freaking me out. But if I had continued to get good marks, I might have ended up being in sciences instead of in the arts. I then found Concordia University—their BFA in Design Art. All the teachers were artists. I learned so much about choosing materials and why we choose them, the symbolic meaning of a material.

I got a graduate diploma in Art Administration. What ended up being the most valuable part of that degree was that I did an internship at an artist-run center called Oboro. That was it—I found my tribe when I went there, and I found other artists, I found out how they lived. I just knew that that’s where I had to be.

TimeTraveller™ is your long-term, episodic machinima project created within Second Life. What was the process like designing the narrative for this project ™?

I start with writing. I write, write, write; I don’t think about the movie. I think about the story that I want to tell. In [the protagonist] Hunter’s case, I knew the main thing I wanted him to be was in the future. I wanted him to be a person who was lost, not knowing if he would make it. I knew I wanted him to learn about who he was and feel a kind of pride and love. I wanted him to be successful. I decided that this movie’s success or this story would be rich and famous because we didn’t see a lot of native people who are rich and famous. It’s not necessarily always what I think is the meaning of success, but it was for this story. I then need to pull out the dialogue, the action, the thoughts. I make a storyboard, and I sketch out little stick figures.

It took me two years to make that first episode; the program was a mystery. At the time, there was no manual for machinima. I don’t think there’s a manual now, either! In the first few scenes that I shot, I was just totally dumb. I made my window different sizes, which gave me all these different file sizes in Final Cut Pro. So I had to reshoot everything. [Also,] I’ve worked with Nancy Townsend [a team member at AbTeC] from (almost!) day one.

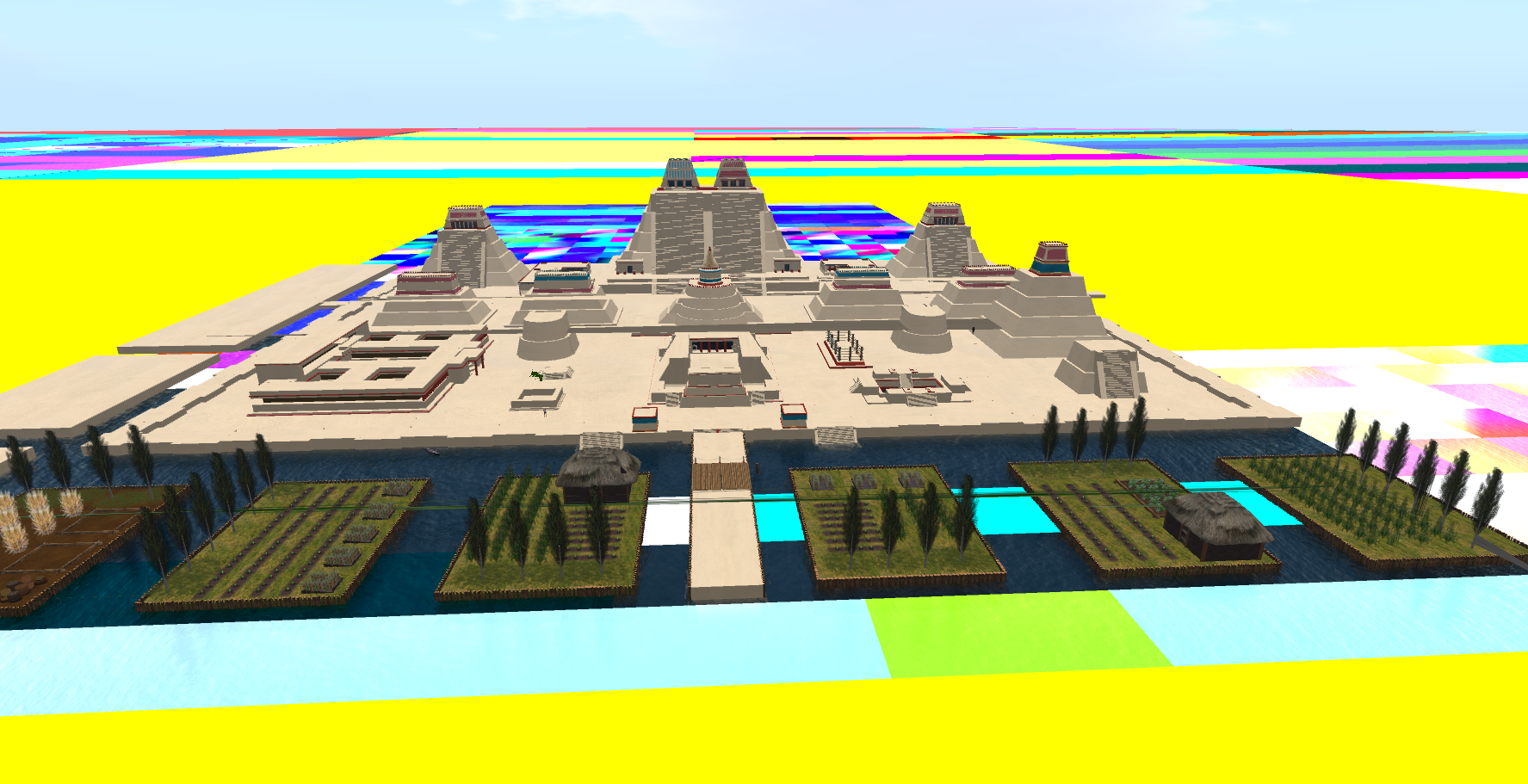

We were learning how to bring imagery into Second Life—how to make a road, how a building. At that point, we were working in other people’s sandboxes or the worlds they’ve created for their own playing or projects. My team figured out that we had to buy ourselves an island. We always think it’s amusing that real Indians spend real money on virtual land.

The technology of Second Life is idiosyncratic. There are so many things you can do, but there’s a lot of limitations too. You gotta just learn to love it. I don’t love the way the hand often goes through the avatar’s body. You can’t control the facial expressions, either. They’re just on a loop, and they smile beautifully, but not necessarily when you want them to. There are all kinds of stuff like that that we have to play with and figure out through editing.

Also, I make character sketches,and then we customize the avatars by buying things on the marketplace. What we can’t find, we make. We also customize things we can buy.

What were the biases that you first encountered when you started working in Second Life?

When I was looking for a Native man’s skin, Hunter’s skin was the darkest skin available on Second Life at that time, and he’s fairly fair. That’s changed—now you have really dark skin, really light skin.

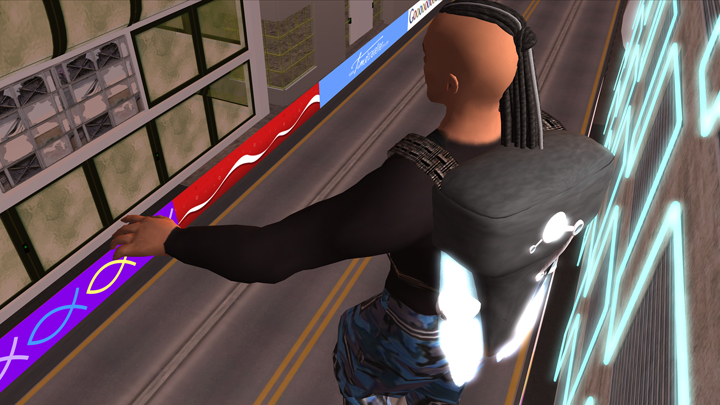

I could never find a Mohawk hairstyle. Finally was very happy, though, finding the ‘dread-hawk’ That’s the name of Hunter’s hairstyle. Over the years, we found a store that made native skins native—specifically supposed to be native North American native people.

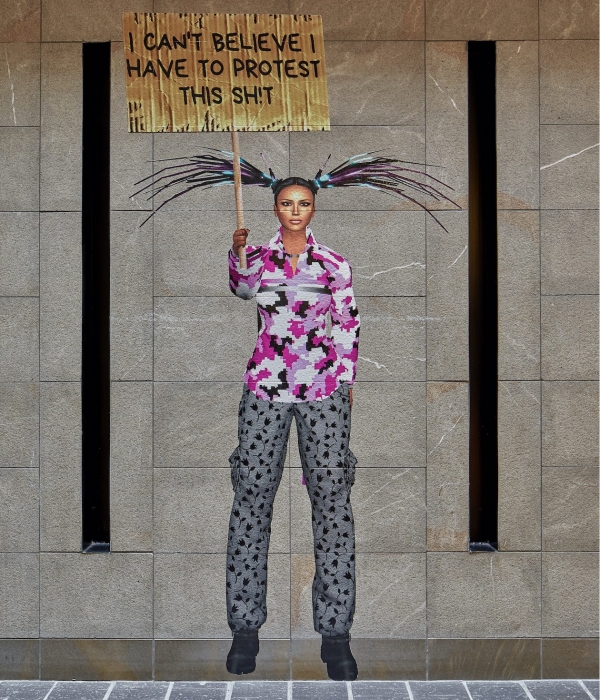

What led you to Calico and Camouflage and thinking about fashion in the physical and virtual protest spaces?

I have definitely been thinking about regalia of the future for years and camouflage as Mohawk clothing as a signifier. One of the first pictures of a Hunter that I ever took, and he’s wearing camouflage pants in there, and that was on purpose.

In 1990, there was the Oka Crisis. That is when I noticed native people wearing army clothes, especially camouflage, and I’ve been sewing calico since I was a kid. We made a ribbon shirt for my avatar. I thought, Why does it have to look like a 16th or 17th-century blouse? Can we make a different shape? Calico is the little flowers that are on the fabric. I thought, What is the future of Calico? When I made episode three of TimeTraveller™, I needed to figure out how to make ribbon shirts. And it was hard to figure out because, at that time, the clothing in Second Life was still painted on the body. It was another layer of skin. In the marketplace, someone who was making callers and you could stick a collar on your neck.

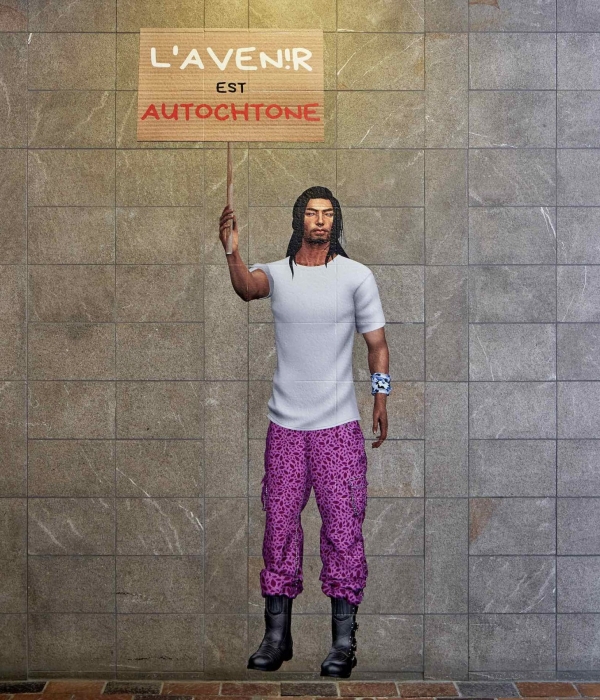

In 2018, I was invited to the first Indigenous Fashion Week in Toronto. I was thrilled. There were all sizes, colors, ages, genders of models smiling, walking. It was this joyous occasion. I thought, “I can do a fashion show in Second Life. I’m going to develop a line in the game for my avatars, and we’ll have a fashion show.” I just knew it had to be what to wear to the demonstration. It had to be resistance wear. I wanted it to be clothing that was ours, and to me, that was ribbon shirts and camouflage. For my project, we decided to occupy the mall.

Ellen Gabriel did a fashion show with camouflage for her community and asked me to be part of it. I acknowledge Ellen for the work that she has done in putting together fashion, protest, and Indigenous bodies in the same sentence.

“The technology of Second Life is idiosyncratic. There are so many things you can do, but there’s a lot of limitations too. You gotta just learn to love it.”

Has your thinking about avatars’ political potential changed in the years you’ve worked in the digital space?

I really felt like avatars could have a strong political power. I really felt they could be something. I’m saying that in the past tense.

I don’t know if I feel that way right now. I think it’s possible again—I see avatars as an extension of ourselves into cyberspace—allows me to go places that my human body can’t go. Especially when I think about Second Life, it’s kind of amazing. But the jury is still out for me on how political an avatar can be.

An avatar allows us to represent ourselves the way we want to be represented. So perhaps we might want a male body if we are born female. I know I’ve enjoyed walking around in a male body in Second Life at times.

I’ve also enjoyed walking around with my little tutu—I can’t do that in the real world. There are things that we can say with our avatars. I realize that that’s what fashion does. I’m starting to understand that fashion is also a statement. I’m seeing the link between fashion and avatars and representing ourselves telling stories with our clothing or what we put on top of our bodies. I do see avatars as another layer of clothing if you will. It’s fashion; it’s representation.

You run AbTeC with Jason Lewis. Can you tell us about the interventions that you’re hoping to make with these educational programs?

As part of AbTeC, We run the Skins workshops on storytelling and experimental digital media, a series of workshops for Indigenous youth, many times taught by indigenous youth, in an Indigenously-determined curriculum.

We’re trying to show young Indigenous people how they can take their stories, whether they be legends or myths or histories or things that are happening to them right now, or dreams of the future or prophecies… and tell those stories in their medium—either games, machinima apps, or whatever’s coming down the pipe.

We want to see young people feeling empowered to use the tools, games, and technology. I don’t think everyone is a producer, or everyone is an artist, but I think it’s important to understand how to use the tools.

Traditionally, many native people are not producers—they’re not in Silicon Valley, in the game industry, or in positions where they feel that they can shape the technology. So this is one of the things we wanted to bring to Indigenous kids. We want them to feel like their stories can be transmediated into these mediums.

When we began, Jason and I faced a lot of resistance from the community. The first person we talked to had never even seen a video game. There was a feeling of a huge mistrust of digital and internet technology. Many people said, No, we don’t want our stories there, because everyone can take or use them.

But other Indigenous people said, Our kids are already playing video games. We need to meet them where they’re at; otherwise, the stories will be lost.

We want to encourage our students not necessarily to leave the reserve but to work, and they could bring wealth to the community. A handful of young, Indigenous people in our Skins program are thinking about starting a company. When your rent is covered, and you’re getting food, that’s when you can really work toward sovereignty and nation-building.

Credits

Interview conducted in February 2021. Edited and condensed for clarity.