A Sound Design: L.A. Noire’s False Notes

When it came to addressing the all-important “uncanny valley,” L.A. Noire didn’t bridge the gap so much as construct an inefficient high-cost rotary over the divide. Plenty of keystrokes have been spent praising, condemning, or simply acknowledging the game’s ground-breaking employment of global illumination and MotionScan technology to accurately capture the facial expressions of all the voice actors. Of course, accuracy isn’t all it’s cracked up to be, especially when it comes to animation. There’s a reason The Polar Express always comes up when this topic is broached, and it’s not because of the quality of the film. It’s because Robert Zemeckis made Tom Hanks look like a wax doll brought to life via Frankensteinian methods. Similarly, while Detective Cole Phelps looked an awful lot like actor Aaron Staton from the neck up, the fact that he carried himself like a videogame character from the neck down tended to ruin one’s suspension of disbelief. And no discussion about L.A. Noire‘s verisimilitude (or lack thereof) would be complete without noting Detective Phelps’ curious interrogation technique; I imagine plenty of folks fond of the game explained away Phelps’ one-man good-cop/bad-cop routine as an outward sign of his PTSD following World War II.

But creating a convincing world in a videogame—not a realistic world; don’t go confusing the two ideas—goes beyond making the characters look lifelike. Attention needs to be paid to every aspect of the game: the look, the feel, and (since this is supposed to be a column about music in videogames) the sound. Even if the elements are seemingly disjointed on a thematic level, they can still work together.

Even if the elements are seemingly disjointed on a thematic level, they can still work together.

One of my favorite examples of this conjoining of strange bedfellows is the Dynasty Warriors series, wherein a carpal-tunnel-inducing, button-mashing take on the Chinese novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms is set to the sounds of either some super-saccharine J-pop ballad or some guitar tech working out his Yngwie Malmsteen jones. Quality of the games or the music notwithstanding, the over-the-top style and action of the game actually meshes with the over-the-top styles of the music used to soundtrack said action. The last two Fallout games pulled a similar trick, scoring the retro-futuristic post-apocalyptic world with jazz standards, pre-Beatles pop music, and country classics. At first glance, that combination doesn’t seem like the most intuitive one to make, but to the credit of the folks making these kinds of decisions, the retrograde flavors of both elements works perfectly.

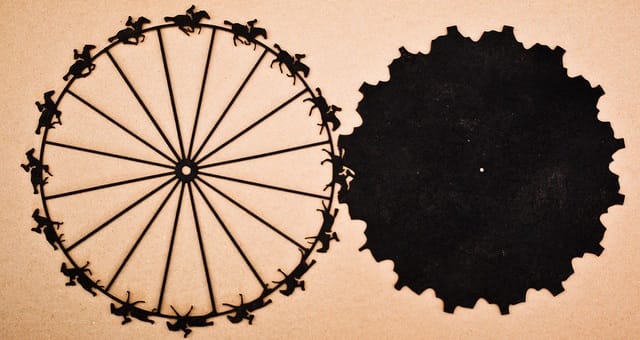

Prior to L.A. Noire, Rockstar Games was renowned for curating the perfect soundtracks for its games. Of course, up until L.A. Noire, almost everything Rockstar has worked on—the Grand Theft Auto series, Bully, even The Warriors—was set in the not-so-distant past, which undoubtedly made it easier for the people making these music selections, or crafting the soundtracks, to find sounds and songs that worked. Red Dead Redemption is the obvious exception in this case, seeing as how it’s probably unlikely that anyone who worked on the game ever had first-hand experience living in the American Old West. Still, the original soundtrack by Bill Elm and Woody Jackson manages to evoke the idea of “the Wild West” despite using a lot of anachronistic instrumentation. That same principle of technically inaccurate evocation is why a caricature of a popular figure—exaggerated facial features and all—can more accurately represent the subject than a painter’s photorealistic rendering of the same person. In metaphorical terms: it’s not about playing the notes right, it’s about playing the right notes.

There’s little doubt that L.A. Noire‘s soundtrack is technically immaculate; both the score (written by Andrew and Simon Hale) and the handful of original songs written by British indie-pop/cabaret band The Real Tuesday Weld sound like the sort of stuff that soundtracked noir films and wafted out of trendy nightclubs. But despite the music sounding right, there’s something just a little bit off about it. This is especially the case with the Tuesday Weld tracks. Despite a valiant attempt from the band to make like a 1950s jazz outfit (complete with sultry singing courtesy of guest vocalist Claudia Brucken), their efforts sound like the work of students that can recite a textbook by heart but don’t quite understand what they’re recapitulating.

In metaphorical terms: it’s not about playing the notes right, it’s about playing the right notes.

Oddly enough, the tracks sound more “realistic” outside of the game. There’s a moment in-game, during a cut scene, when we find Cole Phelps sitting in the Blue Room, listening to current/future paramour/homewrecker Elsa Lichtmann and her band perform one of the Weld originals, “(I Always Kill) The Things I Love.” Whether it was the seemingly sudden transition to the scene, or the fact that the scene (if I remember correctly) brings the viewer in mid-song, I couldn’t have been taken out of the game more quickly if my Xbox 360 decided to crash. It was as if the song was a lie that was being told so desperately and so emphatically and with such overwrought detail that it rang false right from the start.

By itself, these complaints about the music would just be a minor nuisance. In conjunction with all the game’s other failed attempts at “realism,” however, it was one nuisance too many. While folks can quibble about the good the facial expression actually did for L.A. Noire, at least that choice was made in the interest of pushing the medium forward and opening up new avenues for game makers to explore. What’s most galling about the musical missteps is that hewing so closely to recreating the sounds of the past shows a lack of imagination, the kind of pitfall that any respectable game company—especially one of Rockstar’s caliber—should easily avoid.

A Sound Design is a monthly column dedicated to exploring the world of music and other blips and bloops. Raposa is a staff writer at Pitchfork and can be found at False Binary.