To play Nintendo’s Steel Diver: Sub Wars is to try and escape from the Great Molasses Flood of 1919. This sounds like a pithy, made-up comparison, but the aforementioned disaster was a very real event that took place in Boston’s North End after a factory explosion; the resultant ooze swept through the streets, killing twenty-one people. But isn’t molasses a sticky, unctuous goo, more Blob than Tidal Wave? Not when heated above its boiling point and moving at 35 miles per hour. The same contradiction exists in Sub Wars. Everything you do in this game feels one-quarter the speed at which you play other similar games. And yet when the proper momentum is gathered, what began as a stodgy pipe hurtles past with the pace of a missile.

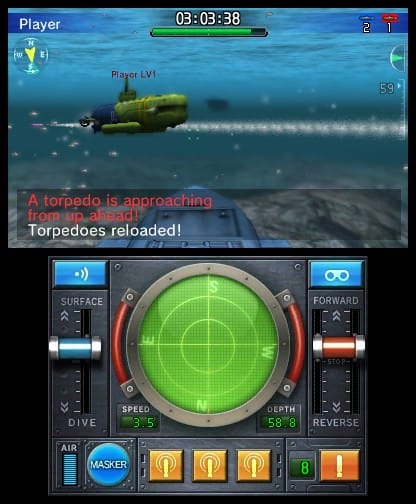

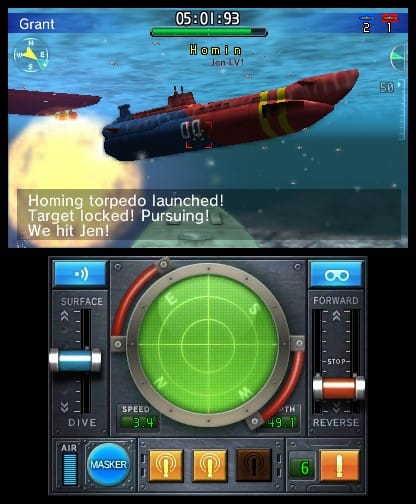

Sub Wars is a submarine first-person shooter. The game is split into seven solo missions with three levels of difficulty, and a four-on-four multiplayer mode, the set-up a familiar team-based deathmatch: Even the team colors are Red vs. Blue. You control your submarine by a handful of gauges and switches: Surface or Dive, Forward or Reverse. Everything about the game, from presentation to controls, is simple, succinct, and slow.

A few deliberate choices turn what might have been an exercise in drudgery into this strange, propulsive thrill. More traditional first-person shooters grant you a familiar perspective. On foot, the constant shift in your surroundings makes the speed and direction of your travel immediately obvious. That perspective flattens in a vast ocean. But look carefully and see a stream of tiny bubbles from your submarine’s cockpit; they push past as you surge forward, or drop below your vantage as you rise to the surface. The pace at which a heavy metal pod can shoot through the water already feels laborious. The clever inclusion of these information-rich bubbles, not only as an immersive sensory detail but also practical feedback, is one of many decisions by the developer, Vitei, that makes Steel Diver: Sub Wars oddly compelling.

FPS standbys are present but wholly unfamiliar. Cover mechanics comprise floating behind a growth of coral; your loadout is always two types of torpedoes, one that shoots straight and another that homes in on a locked target. The game is a course-correction for a genre that year-on-year relies more on cinematic set-pieces than a controlled mastery of your environment. Long divorced from the necessary corridors of Doom, many first-person shooters still offer a mainly linear experience. Go here, then here. End up here. Explosion. Since Sub Wars takes place underwater, you’re often tasked with navigating a wide expanse of ocean; it’s hard to go straight even if you try.

During the game’s reveal this month, Nintendo president Satoru Iwata described Sub Wars as a “contemplative” FPS. And indeed, you have much time to ponder the inevitable crash of metal on metal as an opponent’s weapon hurtles towards you. There’s little you can do. The tension is unbearable. You turn. You engage thrusters. You edge away from the projectile’s incoming line. It sails just over your hull. You feel the miss more since it seemed unavoidable.

What is invisible in a traditional gun-based shooter becomes boldly apparent in Sub Wars. You don’t see bullets scream past your face as opponents barely miss their intended head-shots. Here, the bullets are a thousand pounds and as long as a car. You notice when one slips by.

In Online Multiplayer there’s even a kind of voice-chat, tweaked brilliantly to be context-appropriate: You tap out Morse Code to teammates. Open the communication channel on the bottom screen and the entire alpha-numeric system is laid out before you. Input the necessary dots and dashes and the appropriate letter pops on screen. When your composition is ready, press A to send it over the waves.

In the online lobby waiting for players to join, the two minute waiting period becomes a stuttering sequence of simple messages. “HI,” one will say. “HOLA,” another says. “ESP?” comes the response. “SI.” Another player buts in: “AZUL.” I laughed at that one for awhile. Just as underwater movement makes us relearn the rules of a simple deathmatch, morse code makes us all elementary speakers again. Even to share basic thoughts takes time.

This is a cat-and-mouse game set in slow-motion; this is sloths vs. elephants underwater.

Indeed, the word “torpedo” comes from the Latin “torpere,” meaning to be stiff, or numb. An impatient player might describe the game as such. There are no boosts or rapid-fire. Just torpedos and the achingly extracted pace of a giant submersible. Yield to its deliberate manner, though, and be hypnotized by its charms. You have to train your mind to expect delayed feedback. This is a cat-and-mouse game set in slow-motion; this is sloths vs. elephants underwater.

This is also free. There is zero friction on the path between you and these waters. It’s less “freemium” than it is Over-The-Air broadcast. You have access to the entire online multiplayer experience, playing with other sub warriors worldwide. But only two of the seven solo missions are unlocked, along with two of the eighteen subs. You won’t be hounded to pay. More like rabbit’ed: Click the “About the Premium version” banner, set on the bottom of the title screen, and a cartoon rabbit looking very much like Peppy from Starfox explains the expanded feature set while QVC-styled muzak plays softly in the background.

Even this approach to the nascent Free-to-Play pricing model feels more like a torpedo than mobile’s incessant demands for in-app purchases, a constant long-range sniping that turns play into fleet-footed avoidance. This purchase is a single, slow-moving explosion, to avoid or not. Nintendo may be late to the party, and their dance moves may be more your Uncle’s drunken swerving than your little cousin’s erratic pop-and-lock, but they are here, big and obvious, and taking the steps that feel right to them. Their purposeful, strange segue into the world of FPSs and F2Ps proves that confidence need not be bombastic or loud. Every person’s contemplations are their own.