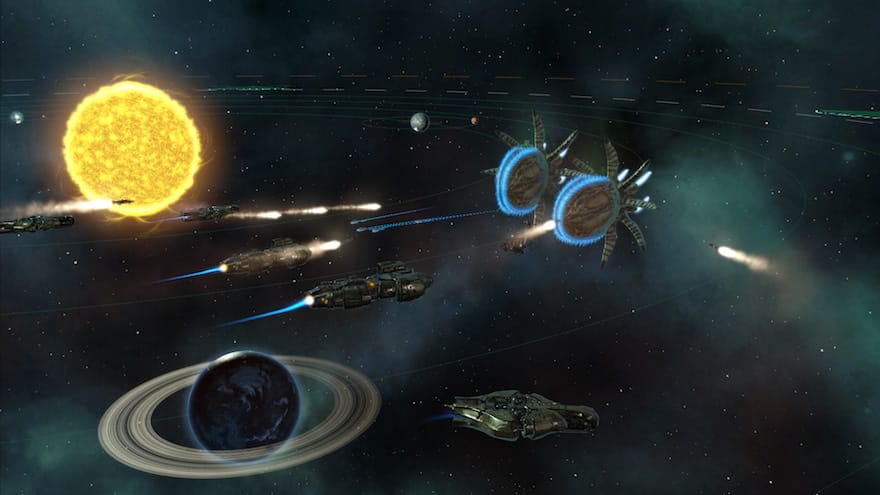

In Stellaris, every star looks the same

There’s a moment in Dreamer of Dune—Brian Herbert’s 2003 biography of his father, science fiction author Frank Herbert—that is worth noting for the way it skirts the idea of reference in sci-fi. It describes the Herberts’ reaction to the release of Star Wars in 1977:

“The film was shocking to me, for all the similarities between it and my father’s book, Dune. Both featured an evil galactic empire, a desolate desert planet, hooded natives, strong religious elements, and a messianic hero with an aged mentor. Star Wars’ Princess Leia had a name with a haunting similarity to Dune’s Lady Alia of the noble house Atreides. The movie also had spice mines and a Dune Sea.

I phoned my father and said, ‘You’d better see it. The similarities are unbelievable.’

When Dad saw the movie, he picked out sixteen points of what he called ‘absolute identity’ between his book and the movie, enough to make him livid. He thought he saw the ideas of other science fiction writers on the screen as well, including those of Isaac Asimov, Larry Niven, Ted Sturgeon, Barry Malzberg, and Jerry Pournelle.”

What’s interesting about the quote is Herbert’s simultaneous inability to see distinctness despite commonality—as though Lucas’s Jawas are the same as Herbert’s Fremen—and the complete lack of acknowledgement that he himself had lifted (just as Lucas might have lifted from Dune) details from other sources: an entire language from the Middle East, and a whole theology from Islam. Dune uses words like mahdi, dar al-hikman, shaitan, jihad, and shai hulud, which are Arabic and refer back to various concepts in the history of Islam. In the same vein, Alia’s house—Atreides—situates Dune in reference to the doomed family of the mythic Atreus, where brother murders brother, uncle murders nephew, father murders daughter, wife murders husband, and son murders mother. Books are made of other books: Lucas was no more stealing from Herbert than Herbert stole from Aeschylus.

Nevertheless, science fiction has a habit of lifting from earlier works as a part of its grounding. Arthur C. Clarke used the image of the devil in Childhood’s End (1953); Dan Simmons’ Hyperion (1989) and Fall of Hyperion (1990) relies heavily upon the writing of English poet John Keats—the second book even stars a reborn Keats. Dune, as mentioned above, lifts the Middle-East and Islam onto Arrakis. Asimov’s Foundation series was inspired while reading 18th-century historian Edward Gibbons’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776). This is not to say that only historians can write science fiction—only that the best sci-fi, like the best horror or fantasy, never stands solely for itself but represents something else. Reference then becomes a way of making the metaphor clear—not as shorthand, but as a tool; not as a crutch, but a color on the palette.

reference then becomes a way of making the metaphor clear

In this context, the previous work of Paradox Interactive—the development studio behind Stellaris—is worth commenting on. In all of the studio’s previous grand strategy games, the player is presented with a more-or-less historically accurate map and then given the opportunity to kick the orthodox narrative off track. Starting Crusader Kings II (2012) in 1066 gives the player the opportunity to replay William the Conqueror’s claiming of the English throne. Alternatively, she can save Harold Godwinson from receiving an arrow to the eye, and repel the Norman bastard’s invasion. In the utter alternative, she can win England playing as Harald Hardrada, the Norwegian king also invading England at the time. Christianity can fall to a reformed, rejuvenated Norse faith, England can win the Hundred Years’ War, and a united China could westernize in 1884. In essence, the model of Paradox Studio’s historical games is that of fanfiction: an established canonical narrative is presented (i.e., our history) and the player is free to write their own divergent story—say, that of a restored Muslim Andalusia or an Axis-allied Greece—which buds out from the host narrative.

Stellaris is distinct from this model, however. There is no canonical narrative or setting for the game to appropriate. It is a grand strategy game like the Europa Universalis series or Victoria II (2010), but it places players in the role of a nascent stellar empire. Having just discovered faster-than-light travel, and armed with a species of customized appearance (from a six-eyed koala to a fungus-based life form) and particular ethos (from militaristic xenophobes to peaceful materialists), the player explores the galaxy and builds a stellar empire. The game is meant to evoke that kind of wide-eyed wonder that the night sky holds, placing the player, at first, in an empty galaxy that holds such promise and excitement.

Yet it remains just as fictive as their previous games, but in a manner largely derivative of earlier works of science fiction. That is, almost every element in the game references something else in the sci-fi canon. The player can create xenomorph armies (1979’s Alien) or gene warrior armies once the “Gene Seed Purification” technology is researched (Warhammer 40,000’s Space Marines) to invade other planets. She can build sentient starships (Ian M. Banks’s Culture series). End game crises can include an alien swarm arriving from beyond the galactic rim (Warhammer 40,000’s Tyranids, or Blizzard’s Zerg), an AI revolt that seeks to exterminate all biological life (Mass Effect’s Reapers), or invasive, blue beings made of pure energy (Titan AE’s Drej). Other, planet-specific events can pop up, including a note about a species of small, brightly colored and highly co-operative creatures that straddle between flora and fauna (as in Pikmin). This is not to say that the game is plagiarizing the original sources, or even lacking in imagination—just that it consciously borrows most of its raw material from elsewhere, and that in turn the videogame represents an aggregate of the cultural landscape that is science fiction.

Granted, not all of Stellaris’ references take their direct cue from existing sci-fi properties—yet they still function the same way. Take one event in particular: the appearance of a small, ceramic object orbiting a star: “It should obviously not be there, yet somehow it has managed to find its way into close orbit.” The event is a reference to a line of argument made by British philosopher Bertrand Russell: “nobody can prove that there is not between the Earth and Mars a china teapot revolving in an elliptical orbit, but nobody thinks this sufficiently likely to be taken into account in practice. I think the Christian God just as unlikely.” The argument’s broader interpretation speaks to the burden of proof being on those who make claims, yet it remains a common barb in the argumentative atheist’s quiver.

Stellaris then becomes a series of inside jokes

The irony in Stellaris’s reference to Russel’s Teapot depends on the player species’s dominant ethos. Some will see it as just a weird conundrum, while the more spiritual species will take it as a favorable sign from the divine. The reference then becomes a clever joke: a point against belief in God is transformed into a point in God’s favor. But its special force depends on the reader getting the reference, just as the Pikmin joke depends on knowing what Pikmin are, and so on. Stellaris then becomes a series of inside jokes, comprehensible especially to those “in the know.”

In relying on references, then, Stellaris looks exactly the way you would expect it to look because the player has been there before, seen it before, and knows what to expect. But in being so familiar it loses that sense of alienness that the promise of space travel entails. And it is not surprising to see that its community is in the process of cutting out the substitution and pursuing the referent. We are a few months away from the inevitable slate of mods to the base game that permit playing in the Warhammer 40,000, Star Trek, Star Wars, and Mass Effect universes—essentially bringing the experience full circle as the game returns, ouroboros-like, to the universes that spawned it. At the same time, Stellaris will receive the regular genuine care that Paradox shows all its games through free patches, adding content, new features, and bug fixes.Though, tellingly, these patches are all named after science fiction authors—Clarke dropped on the first of June, Asimov was released on June 27, and Heinlein looms just over the horizon. Stellaris then operates less as a piece of fanfiction, and more as an echo chamber for these kinds of references.

In that sense, it can be contrasted with the pillars of its source material. Take, for example, the simultaneous and paradoxical familiarity and alienness of Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness (1969), which tells the story of a human ambassador visiting a frozen world inhabited by a unique variant of humanity. Instead of the binaries of gender, those native to the planet Winter are caught in a static, agendered state for most of the month. Every 26 days, those humans then experience a contextually-based shift into either biological maleness or femaleness. Part of the pleasure of the novel lies in those moments where a sense of common humanity is fundamentally undermined by stark difference: without gender binaries to serve as a kind of typological original, the world is starkly mono-cultural and monotone. Large-scale wars—binary conflicts writ large and dramatic—are absent from Winter, while its people view the more traditional division of genders as a perversion.

But despite these alien details, the world is deeply human. One character, for example, faces an exile just as keen as that of Dante’s from Florence in the 14th century. Another is placed in a frozen internment camp that evokes One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1962). These comparisons work not because The Left Hand of Darkness explicitly makes them (it doesn’t), but because they’re both trying to describe the same kind of experiences: bitter exile, forced labor in a frigid environment. References across science fiction work in the same paradoxical way: similitude highlights difference and vice versa. The end of The Left Hand of Darkness asks for stories of the past and stories of the future because the former gives the latter their clarity: “Will you tell us how he died?—Will you tell us about the other worlds out among the stars—the other kinds of men, the other lives?”

The Left Hand of Darkness tries to portray alienness in a way very different from Stellaris: it does not rely upon shorthand, but upon the portrayal of the alien qua their own alienness and hence familiarity. Like Mass Effect, Dune, Foundation, and countless other sci-fi universes, it builds its extraterrestrial world from the ground up. Stellaris only borrows from all of their palettes to paint its own picture of the night sky—and a game about aliens feels all the less foreign as a result.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.