You are the center of attention in Tom Russotti’s Opener

“Alright, Blue, that’s a warning. I’m watching you.”

Tom Russotti is talking between his teeth, clenched with a neon gym teacher’s whistle. Admittedly, I deserved the warning. I had just barreled shoulder first into an opposing player, flailing my free hand in his face whilst clashing together the antler-esque hula-hoops duct-taped to the bike helmets on our noggins. I gave a brusque penitent nod and gallop down the field towards a scrum of players desperately passing a plastic inflated ball back and forth, trying to line up a shot through the head-mounted hula hoops.

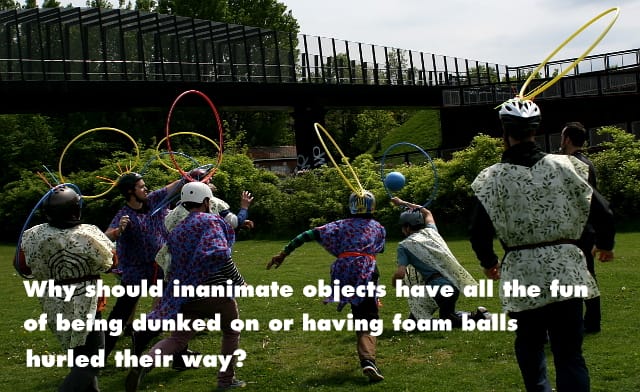

Twenty minutes later, end of the second half, 5-4, I am charging a huddle of teammates dressed in pink/blue plaid intermixed with our taupe-tuniced foes in the goal line, my head lowered and face turned up to the sky, bellowing “Dunk it! DUNK IT!”We’re playing Opener, a sport invented by Tom Russotti’s Institute of Aesthletics and part of this past weekend’s Come Out and Play festival. It’s called Opener because the players—with a hula-hoop ducttaped straight up on top of their heads—look kind of like bottle openers. I had a chance to play in the fourth Opener match in world history at the inaugural w00t festival in Copenhagen a few weeks ago.

Opener is a game that transforms the players themselves into goals. Why should inanimate objects have all the fun of getting dunked on or having foam balls hurled at their way? Like many of Russotti’s new sports, Opener plays around with the fundamental building blocks of physical games with outstanding results. Turning the players into goals completely reconfigures the heroic individualism of scoring in games like baseball and soccer, making each point into a cooperative effort instead of an individual victory that benefits the team. Russotti and other Wiffle Hurling enthusiasts dreamed up Opener after they got tired of lugging around soccer posts every time they wanted to get a match together.

All of its equipment can be carried by one person, albeit with some assembly required. I asked about the fetching uniforms made for each player. Russotti is self-deprecating: “Whatever shit I can find for cheap in the department stores of Brooklyn.” Later, he tells me the blue/pink floral getup is inspired by ground-breaking color photographer William Eggleston’s Woman on a Swing and the taupe-floral pattern were once bedsheets that reminded him of William Morris’ Arts and Crafts wallpapers. “Whatever shit I can find for cheap in the department stores of Brooklyn.”

Those art-world references hint at Russotti’s background and his work with the Institute of Aesthletics. Russotti has an MFA in Visual Art from Rutgers and started the Institute after the 2005 invention of Wiffle Hurling, a team-based competitive sport with wiffle bats. He’s traveled the world, encouraging people to get involved not just with playing sports, but designing them too. Russotti shows people that sports are just as worthy of artistic consideration as other forms of culture, and in the process de-institutionalizes sport. The Institute of Aesthletics gives players permission to create new games and change rules in pursuit of fun and beauty. Russoti shows people that sports are just as worthy of artistic consideration as other forms of culture.

Here’s how Opener works. Two teams of five square off on opposite sides of a field with two endzones. Play begins with a kick off of a plastic ball, and anyone who catches it has to throw it before taking two steps. Each team wants to gain possession of the ball and throw it through a goal in the endzone. The catch is that the goals are attached to the players’ heads. Players can score double points by hugging each other (taupe team) or stretching out into a star-shape with arms and legs splayed (pink/blue) or by getting the ball through multiple hoops. Opener is as much performance as it is sport, brilliantly exploiting the lines between costume and uniform at one moment, competition and art the next.

After the second half, Tom slowly changed into a mutant player-referee. When he joined, he donned the taupe tunic of the other team— that is the team that was up three points and composed of tall dudes. Not only that, I could tell Tom was in it to win. Things looked pretty grim until I realized we couldn’t go on getting totally shut down trying to pass while covered by towering Danes a head taller than anyone on our team. Instead of trying to get open while my teammate tried to peek at me through a solid wall of enemy-team meatbags, I pioneered the reverse dunk. If the ball can’t get to the goal, the goal must come to the ball. I turned my head sideways and bowed low before charging. My baffled teammate plunged the ball through the hoop. We turned the match around and beat Tom at his own game.

I felt like Dr. J taking basketball above the rim. That’s the beauty of getting to explore a new sport—creating new tactics that redefine the way the game is played, at least until people figure out how to adapt to an unexpected way of playing.

Additional editorial support by Alexander Saeedy.