Stray From the Path

A woman in her late teens follows a warm bright path and crosses a wooden foot bridge to her darkened and foreboding grandmother’s house. She’s made it; she’s safe. Suddenly, the scene transforms and she’s back at home with her sisters instead of inside Grandmother’s house. Why has she returned? She has been given the instruction to stay on the path and make her way to Grandmother’s house, but she is returned to the beginning if she follows the directions.

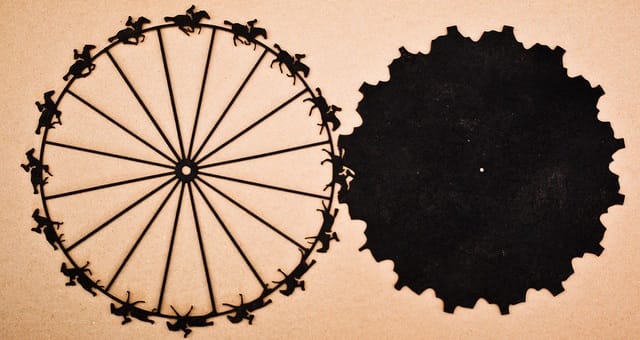

Navigating the forest in the videogame The Path (2009) by Tale of Tales, I am reminded of Jeppe Hein’s Invisible Labyrinth (2005). In Hein’s work, participants are invited to wear a head set and wander an empty gallery, facing the consequence of a loud buzz if they hit an invisible wall in the labyrinth. Through the series of buzzes participants in Hein’s work must find the centre of his invisible labyrinth, which changes every day. In The Path, players control one of six female characters and guide her to Grandmother’s house. Players can follow the road to Grandmother’s, or wander with little sense of direction through the surrounding forest. While the context of Hein’s work and The Path are different, the repercussions of ‘hitting a wall’ or venturing off in the interactive landscape of The Path are similar.

Instead of following the “rule” (stay on the path) players in The Path can make their female avatar stray into the mysterious woods and explore the world beyond the safe illuminated path.

The Path is a game where art and popular entertainment collide.

The sunlight fades and she finds herself surrounded by a fog, only able to see so far ahead. In the distance she sees a glowing white object moving and she runs towards this bright form. She encounters a younger girl in a white dress dancing and playing amongst the trees. The older teen invites the girl in white to play a quick round of pat-a-cake. Then the girl in white takes the older teen’s hand and they race towards to the sunlight, once again on the safe path. The older teen invites the girl in white to follow her to Grandmother’s house and the girl in white retreats back into the forest, gesturing a warning and vanishes into the forest. Once again the teen is alone.

Like the buzz in Hein’s Invisible Labyrinth and his Appearing Rooms (2004) fountain installations, the participant is warned to stay on the path, suggested by the buzz, or face the consequences. When I first explored The Path and Hein’s labyrinth, I was surprised because neither is typical of their genres. The Path has little written narrative, only the suggestion to journey to Grandmother’s house and “stay on the path.” Hein’s installation is an empty room insisting upon participation to activate the work. The Path is a game where art and popular entertainment collide. You can’t “win” in The Path, there’s no competition nor is there a single experience. The Path isn’t “fun” in the traditional sense of a game, nor does it provide instant gratification; instead it is a meditative horror requiring contemplation. Like Hein’s interactive art work, the player participates in the journey and actives the work.

The player continues to wander the woods, leading the teen to a desolate playground; there is a man there, he’s smoking. His slicked back hair, tight jeans, and black t-shirt announce by stereotyping that he is dangerous. The teen had noticed him earlier dragging a rolled-up rug through the woods; what could be inside it? My instinct is to avoid and ignore him, but I grow more curious and less cautious. She sits beside him on the park bench and both look out on the abandoned playground. Her body language is anxious, he offers her a cigarette and she takes it. I’ve changed my mind, I want her to leave but I can’t make her leave; there is no escape. As the two smoke their cigarettes the scene grows dark. The scene fades in revealing the teen’s body unconscious outside of Grandmother’s house. It’s raining. There’s the sound of a beating heart. Is it mine? She awakens and lifts her broken body off ground and stumbles slowly, defeated to Grandmother’s house.

There isn’t a detailed description of what happens to the girls when they encounter their ‘big bad wolves’. These ‘wolves’ primarily take the form of older men; however there is a literal wolf and a young female playmate who also victimize the sisters. Instead there are fragments that suggest narrative rather than clear answers. These snippets make The Path a cognitive experience like a work of art, requiring the viewer to reflect on what they are experiencing and construct a narrative. The premise of the game isn’t presented but instead has to be worked through, allowing players to think for themselves and ask questions about the game. Do I protect my protagonist from harm or do I curiously venture without worrying about consequences?

The shifting color scheme and elegant growing and retracting lacing pattern on the side of screen reminds me of Jeremy Blake’s Winchester Trilogy (2002-2004) where his video explores the enigmatic Winchester Mystery Mansion. The forest is similar to Kelly Richardson’s Leviathan (II)(2011), a twenty minute loop of a swampy misty forest in Caddo Lake in Uncertain, Texas. The Path, Blake and Richardson instil an experience of eerie calmness and an unsettling lurking horror. The Path’s ominous forest and Richardson’s landscapes share an uncanny and pristine naturalness disrupted by rogue elements. In Richardson’s landscapes it is the introduction of a day-glow green deer and fireballs, in The Path it’s the abandoned car, television and shell casings; each begging unanswerable questions.

After the ‘big bad wolf’ encounter in The Path, Grandmother’s house becomes a labyrinth of nonsensical interconnecting rooms, like the Winchester Mystery Mansion that haunts Blake’s video. While gliding through the house there is a strobing surreal symbolic montage of the teen’s encounter with the older man and her grandmother. It sends chills down my spine; how will Grandmother punish the young woman, since she strayed off the path?

When encountering these ‘big bad wolves’ in The Path, players innocently assume that they’ll be safe. How many times have we sat on a sat park bench and chatted to a stranger? Shock, horror and disbelief overwhelm the player as they piece together the unseen violent event. Like Blake’s Winchester Trilogy, the piece allows for the viewer to delve into the darker and terrifying places of their greatest fears.

Contemporary society still insists that if women venture alone they welcome misfortune.

The Path even has a bit of social commentary. It reinforces and allows men to experience the fears that are indoctrinated in women from a young age: “Don’t stray from the path” and don’t be alone with a strange man. Contemporary society still insists that if women venture alone and dress “scandalously” they welcome misfortune and deserve punishment for disobeying the order of perceived cultural norms. Grandmother’s punishment isn’t too far from recent news stories. Victims of sexual assault or rape are subsequently tortured by the media, branding them as either liars or temptresses and others proudly exclaim “she deserved it.” The Path also presents the negative male stereotype that men are unable to stop themselves from harming women and always intend to harm them.

The Path represents a new generation of videogames. Developers are experimenting with the possibilities of the visual, experiential and interactive media of gaming; asking players to be patient and causing them to sympathize with the on-screen protagonists. Similar to Hein’s labyrinth, Blake’s mansion, Richardson’s landscapes, The Path frightens us to stay on the path, but tempts our curiosity to stray.

[img]