The strikingly minimalist Spacecom says only what it needs to

A few months ago EVE Online had its most massive battle ever. With over 2,600 pilots and at the cost of over 75 titan class ships (worth, it was widely reported, about half a million real-world bucks), the battle lasted nearly an entire day. Its song will be sung throughout the annals of EVE history.

Scale has always been a touchpoint for space games, but it’s also one of the drawing factors of space in any medium. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy memorably told us that “space … is big. Really Big. You just won’t believe how vastly hugely mind-bogglingly big it is.” It is part of the great hubris of man to attempt to fill that “mind-bogglingly” large expanse with moon-sized Death Stars and almost mile-long capital ships. So massive are stories told in space that they have their own massive sounding subgenre, the space opera, which attempts to encapsulate not only the rugged frontiersmanship or wars waged across the stars, but also the melo- and personal drama which come with it.

This massiveness has found its way into space games too. Games like Star Wars: Empire at War, Homeworld, and Planetary Annihilation live off of a desire for the theatrical and the grand. There was no fleet too large or foe too big. The solution was always simple: build more ships. I was conducting Sherman’s March to the Sea on a galactic scale; I was become death, destroyer of worlds.

But it’s a force that is completely senseless, as all violence is in the end. There is no subtlety, no craft. The joy that one receives from crushing an opposing force vastly inferior in numbers is that of the school yard bully. I will not deny partaking in that joy, of launching an armada against an outpost, of building armadas in order to spread my fiery dominion across a star map. But there’s one game that’s got me thinking of how hollow such victories are: Spacecom.

Spacecom, which was recently released and still being worked on, is about as bare bones and minimal as you can get. When developers 11bit Studios say that it’s stripped down, they seriously mean it. Spacecom is almost the opposite of the aforementioned games. There are only three unit types, no tech tree, no nested build queues, no flaming hull or burning planetscapes. There is just you, the tactical map, and the endless, haunting minimalism of space.

The sparseness of the screen is, at first, a jarring change. This is space distilled, taken from raw materials, refined, and laid out without the fussing and elements that many games have. There is no economy to manage, no citizenry to keep happy; there is just you and the war. A war presented in perhaps its purest form, exactly as one might imagine some future admiral poring over. That future person would have no need to see ion cannons or laser fire; such a commander would only want the information, and in a way that would allow her to make the best decisions as quickly as possible.

There is just you, the tactical map, and the endless, haunting minimalism of space.

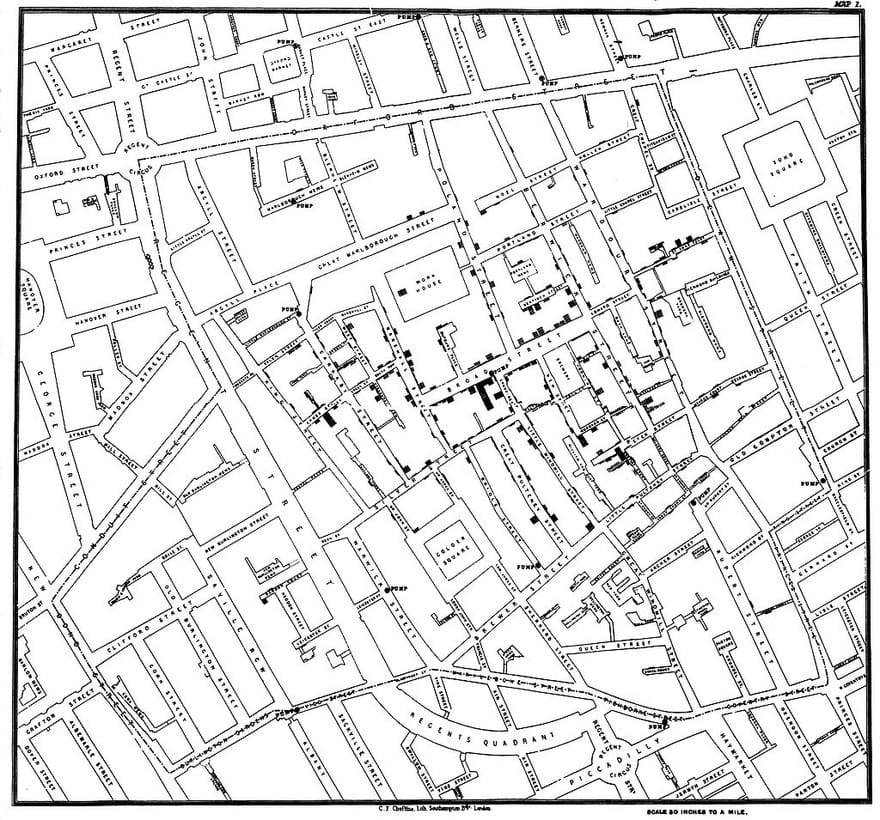

In some ways, this interface is what a game made by data scientist Edward Tufte would look like. Spacecom allows one to maintain what Tufte calls “analytical seeing … try[ing] to stay in the sheer optical experience as long as possible.” Tufte wants information to be accessible instantly so that the viewer can take time to interpret, analyze, and decide. Jon Snow’s famous cholera outbreak map, which overturned the prevailing notion that cholera spread by some airborne miasma, is one that Tufte cites as “a graphical display that provided direct and powerful testimony.” The “no frills” approach in Spacecom allows the player to see nearly every necessary bit of data in order to best assess the situation and plan, adapt, and conquer. 11bit knows this well—lead designer Kuba Stokalski told me he believes that “abundance is often mistaken for meaningfulness” and that “there are too many games that provide false value, mistaking feature bloat for meaningful experience.”

This design philosophy in Spacecom makes analytics easy but decisions hard. Spacecom does not teach you how to win—actual strategy teaches you how to win. Stokalski also believes the game “tries to give way to a pure ‘battle of the minds’.” The game wants you to be Ender Wiggan; it wants you to you plan, strategize, and destroy.

Though you can still build (somewhat) massive fleets, Spacecom does not reward massiveness or scale. Spacecom rewards thoughtfulness. It rises against scale games like Planetary Annihilation; there are no super weapons and the only way that your ships can get stronger is through experience. It’s even contrary to Risk, in that there is no luck and something is always happening. The website broadly warns this is a game “FOR GREAT LEADERS ONLY.”

But Spacecom is almost too minimal at times. Occasionally, one player is able to gain control of most of the major resource points and sooner or later the inevitable happens, you are crushed. This is late-game inevitability is a weakness of many strategy games, one that few have creatively been able to circumvent. But these moments too allow for greatness. We do not remember Leonidas and his 50,000 Spartans because of their overwhelming victory. Instead, we remember them the same way that we remember the time your one army on Kamchatka last turn after turn against a superior force.