Struggling to breathe in a real version of the terrifying space sim Capsule

The breathing in Capsule is intense. “Some people think it sounds like a dude who’s getting it on,” says Adam Saltsman of the sound design in his new game of single-handed space exploration, “rather than being legitimately terrified.”

Whether it sounds pornographic or petrifying, Capsule’s breathing is only the beginning of a journey which relies heavily on audio to build its world. Your astronaut’s breath is heard because it “makes it sound like an enclosed space,” says Saltsman.

Robin “Deep Sea” Arnott’s other elements of sound design capture the terror of space with remarkable effectiveness. With oxygen depleting, you thrust about to find resources to collect and deserted stations with which to interact. You listen to a kind of audible emptiness, and the clunking mechanics of your craft.

Inspired by Lunar Lander, Saltsman wanted to make a game that didn’t simply end when the player’s vessel ran out of fuel. Capsule makes you wait for the oxygen to run down and, in that silence, the only sound is choking. While you spend much of Capsule listening to yourself breathe, it’s a journey that ends when you listen to yourself dying horribly.

Everything I do feels like a life-or-death decision.

At the GameCity festival in Nottingham, England, Saltsman collaborated with festival organisers to present Capsule Capsule, a site-specific version of the game that lets the player become the astronaut.

From a sign-up desk in the festival’s main tent, I’m led through the city’s maze-like commercial streets by a guy whose white coat confirms that the white coat is still the cheapest way to make you look like a doctor or a scientist. I’m instructed to wear some headphones for the walk, through which the mood is set. Robotic voices cycle through numbers, conversations mix with Dharma Initiative-style instructions, and doom-laden noises sound in the background. What I’m hearing and what I’m seeing are so in contrast that I can’t help but wish that the festival’s budget would stretch to the kind of world building you see in theme park queues.

We arrive in an alley. A jumpsuit, rather than a spacesuit, awaits. Then we head down. It’s a game set in space and I’m playing it in a basement, but more appropriately it’s a dark, creepy game and I’m playing it in a basement.

The capsule is a tiny room, shielded from the light and heat of outside with silver foil and black cloth. I sit down, a control panel—a joystick and an arcade button—swings down across my lap and the room goes pitch black but for the monitor in front of me.

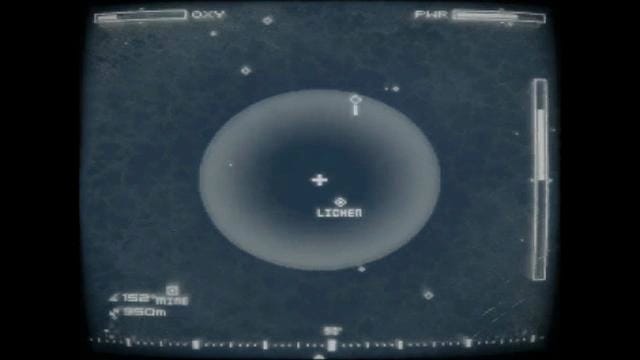

The view is taller than it is wide, designed to look like the realistic display with which our astronaut might have to navigate the darkness. Its navy-and-white pixels flicker and strobe just like you’d hope they would in the unprotected vacuum of space.

Above: Adam Saltsman

Everything I do feels like a life-or-death decision. I feel like I’m in the strangest arcade, down to my last credit, and this is my only chance. I’m getting stressed because I’ve forgotten most of the instructions. I know I need to navigate to the first station, but I forget to use my pulse to identify useful space debris. Disoriented, I waste all my fuel in 30 seconds and my panic and my astronaut’s panic are one. He dies a horrible death, though, and I don’t. The screen fades; I wait, breathing pure relief when I respawn, and reacquire some of my senses.

Saltsman wanted Capsule Capsule to make the player feel “extra uncomfortable”. With its sensory deprivation and sense of peril, it works. There’s a sense of responsibility for a human life, and enough mystery to constantly worry that this life is always in danger. Saltsman agrees that the game feels like a weird arcade because “despair and existential panic are not the core emotions you’re trying to get out of people [in a regular arcade].”

Immersion may be a dirty word in games, but Capsule Capsule exemplifies it. How do I know? As I listen to my astronaut’s final moments, I realise