Suits: A Business RPG asks how easily you’ll give in to a corporation

The enemy here is capitalism. Isn’t it always?

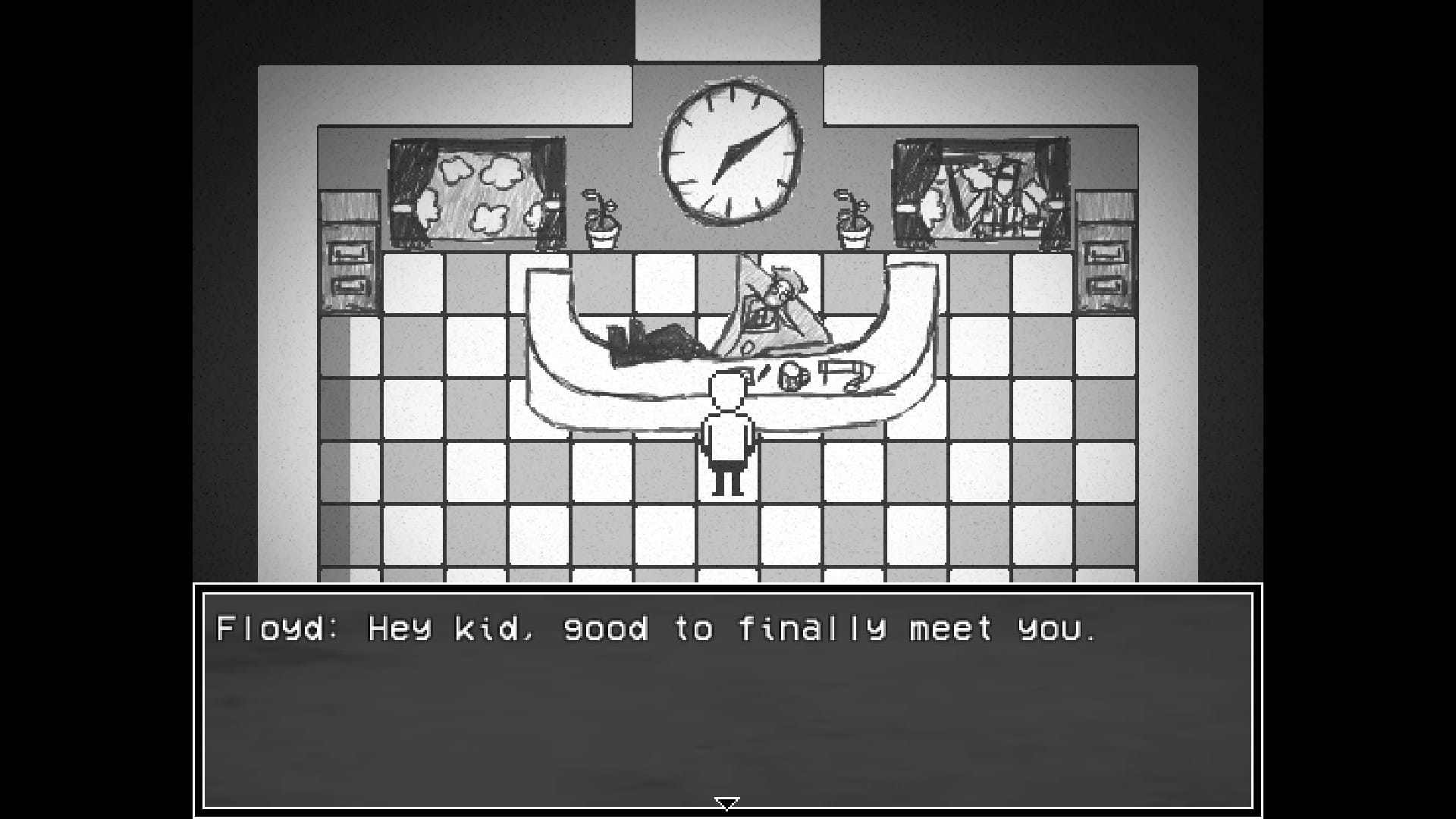

Suits: A Business RPG is an expedition into the morass that is modern capitalism. Note that it is not a journey through this world. That would presuppose the existence of an escape, and Suits is not that sort of game. The action takes place in a black-and-white corporate dystopia, though the extent to which this world differs from ours is very much up for debate. “Corporations,” the game’s documentation explains, “control the entire global government.” What’s new?

You play as a businessman. You are not the worst of people, but you’re also not particularly virtuous. You’re just another cog in the machine. The Corporation and its representatives give you tasks to complete. Remember: your corporate overlords value your silence and acquiescence. Do exactly as they say and there’s money in it for you. What else could you want? But let’s say you want more. Well, it’s there for the taking. Not legally, sure, but it’s there. Wealth is all around you, so why not take some? Suits bills itself as “the journey of a businessman’s descent into corruption,” which is not a particularly optimistic view of human nature but a reasonable one nonetheless.

This is a structurally and linguistically corporate world.

Insofar as this gloomy disposition extends to political and economic systems, Suits attempts to make its point through language. This is a structurally and linguistically corporate world. The former isn’t really that big of a change, but it is relentlessly underlined through corporate language. The world, the government, and power itself all take their name from the corporation or, to be precise, The Corporation. This critique of capitalism depends on the viewer already believing that corporations are unpleasant. It’s only slightly subtler than Mr Robot’s “Evil Corp.”

These critiques work because corporations have not exactly covered themselves in glory over the past few decades. The weakness of capitalization as rhetorical strategy—just call it The Corporation—is that it preaches to the choir. If you believe that corporations are somewhat sinister, these works will resonate. But what if you’re on the fence? Suits and, to a lesser extent, Mr Robot don’t really develop a language to criticize the worlds they depict, and the broader concern is that the culture as a whole is failing to do that. These are still valuable and interesting works of social criticism, but their value is limited by their indifference to those who most need persuading.