Super Mario Maker, and the problem of reviewing a community

I’ve already done a bit of hand-wringing about the ways Mario Maker makes me nervous. To put it briefly, I think it’s valid to question whether Mario Maker could ever benignly be a Lego kit full of the bits and pieces that comprise Mario levels because of its social aspects. In that piece, I relate it to the business models of social media websites and the value of free labor: Every post you make on any social media site increases that site’s worth without compensating you for the work you put into the post. Likewise, in Mario Maker players do the work of level design in order to have fun learning and breaking the design process, share their levels, and play others’ levels. Read generously, it’s Nintendo’s trademark “good, clean fun.” More pessimistic players might see Nintendo crowdsourcing design ideas for its next Mario game.

a game like this can only be as good as its community

In my view, a game like this can only be as good as its community, which is why I didn’t score it then. Now that the game has been out in the wild for a few weeks, I feel like we can talk about it in review terms.

But before we do, I want to point out something about the relationship between games and criticism. You might say I was harsh on Mario Maker in that first piece. I questioned the game’s core idea—not whether it does what it tries to do well, but whether it should even be doing what it does in the first place. For me, a critique like that is a way of embracing the medium. Critique is the means by which we take games seriously. Critique means expecting more from them. It’s tough love. The best game writers critique games on ideological grounds, which can be hard to square with the idea of a “videogame review” as we often think of it: a recommendation about how best to spend your money and time, a barometer for “fun,” an attempt to quantify quality.

I’m suspicious of Mario Maker because the role of criticism, in my view, is to ask questions not only about the game as such—on a disk or drive, renderable and rendered—but the game as it relates to our social conditions. I still think Mario Maker reproduces a distinctly Silicon Valley notion of labor, and that still makes me nervous. But—and this is the crucial part—that doesn’t prevent it from being a “good game,” whatever we mean by that. Anita Sarkeesian drives this point home at the beginning of Feminist Frequency’s famous “Damsel in Distress” videos: “It’s both possible, and even necessary, to simultaneously enjoy media, while also being critical of its more problematic or pernicious aspects.” I think that’s one ideal for criticism: to identify the ideas at work in a given medium and separate them out from its effects. For videogames, that effect has traditionally been fun.

And, by that measure, Super Mario Maker is an out-of-the-park success. It synthesizes 30 years of Mario art and design, allowing players to build (literally) from the ground up, or recreate classic levels in order to understand Nintendo’s principles of design. In fact, at first when I saw all of the players online who have shared full remakes of famous Mario levels, I felt a bit confused by all the work that had gone into making a good copy. Isn’t the point of the “maker” part of the title to make something your own? But I’ve come to see it in a different way. There’s this famous anecdote about Hunter S. Thompson copying out The Great Gatsby to figure out—word by word—how Fitzgerald really did it. I think something similar is happening with these remakes: they’re manuscripts, facsimiles, and unwritten instruction manuals. The best way to learn how to make a Mario level is to make a Mario level.

what Mario Maker is at heart: a mash-up machine

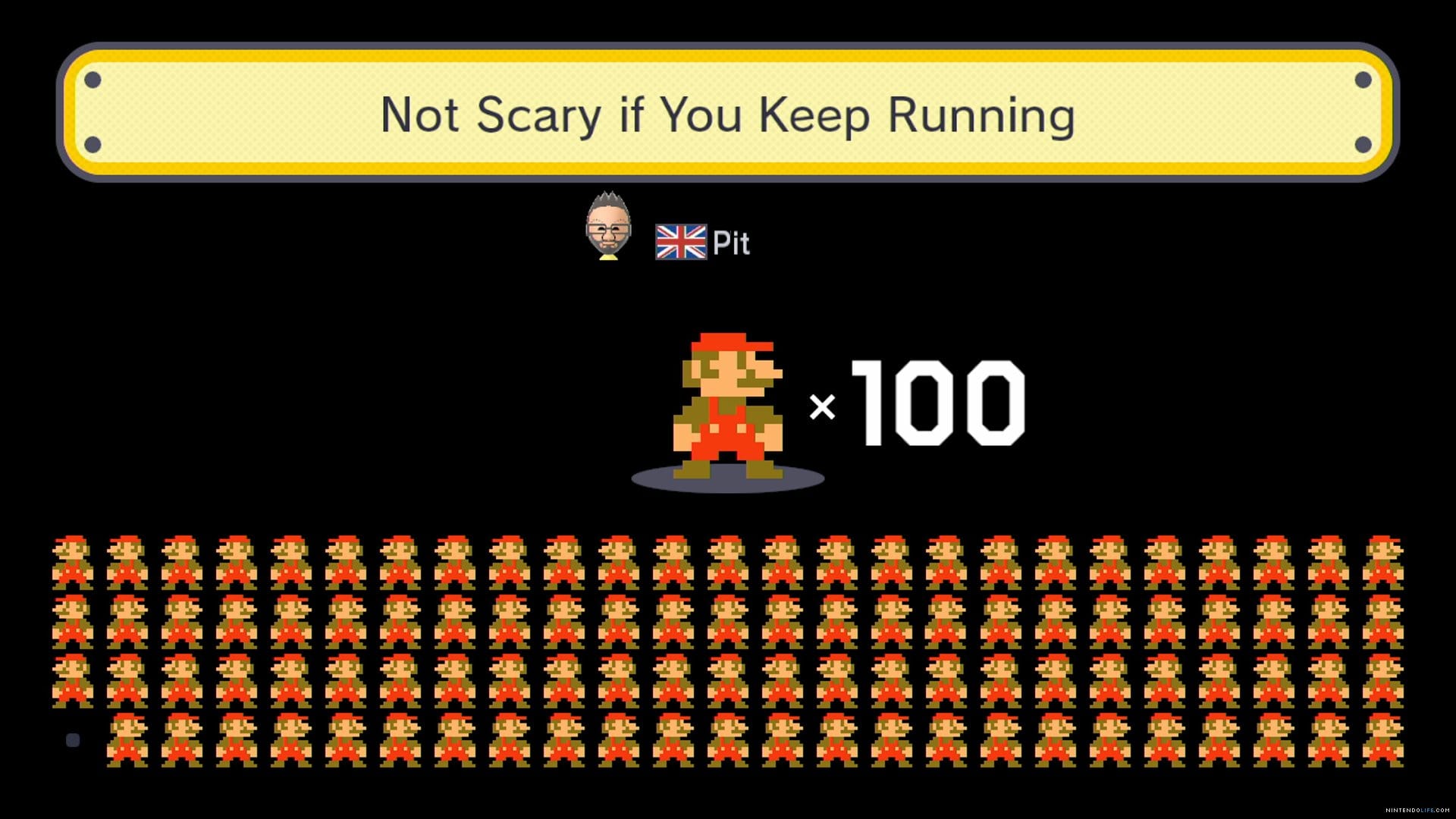

But lots of what the community has done has nothing to do with the Mario canon. There are even a few new (or at least new to me) genres of level that have cropped up near the top of the charts. First is something you might call a museum piece, or maybe a garden walk. This is the type of level where you’re told—via the title or a bunch of coins shaped like letters—to walk, run, or do nothing for the whole level while narrowly avoiding death, stuff blows up, scenes shift, etc. These levels try to recreate the best moments of platformer flow: when you’re running through a level while narrowly yet expertly avoiding death. They’re also bravura performances for the designers, meticulously built roller coasters of koopas, fire wheels, boos, springboards, and all the rest, threatening death with the knowledge of complete safety.

There’s a specific subspecies of this genre that recreates theme songs from various other games using music blocks and perfectly timed falling and bouncing objects. You can walk to “play” the song slowly; run to kick up the tempo. What’s fascinating about these levels is that they operate on an entirely different set of assumptions from prior Mario levels. Where other Mario levels are obliged to provide at least some challenge to the player, focus here shifts from rewarding the expertise of the player to the expertise of the designer.

Of course, some levels hybridize this changed focus on who gets rewarded. There are some unspeakably cruel Mario Maker levels that hew closer to Super Meat Boy than our plumber would ever dare go on his own. Others test your skills from different games. Some of the top-ranked levels duplicate level design from Pac-Man and WarioWare but in the Mario context, which is, I suppose, what Mario Maker is at heart: a mash-up machine. It’s clear the community has taken Mario Maker in novel directions, and that’s largely thanks to the way Nintendo has balanced the level creation tool between ease of use and power.

For all that it has done to rewrite the history of the Mario series (not least through the vibrant community it’s created), Super Mario Maker is a clear success on its own terms and an excellent game constantly in the process of renewing itself. As I argued before, I think it’s still likely that Nintendo will profit from the intellectual labor players invest in Maker, and that we’ll see the fruits of the community’s work in the next Mario game. That said, Nintendo isn’t Facebook. Maybe it’s better to think about it in terms of participation and collaboration than the work of the many in thrall to the few.