Tearing the Fabric

This article is part of Mario Week, our seven day-long celebration of the 25th anniversary of Super Mario World and 30th anniversary of Super Mario Bros. To read more articles from Mario Week, go here.

///

While playing through Super Mario World for the first time, I always made sure to tell other kids at school about how far I’d gotten the previous night. “Dude, I just found this secret that takes you to this crazy star level,” I’d say.

But I was rarely the first person to get to this point. There was usually some cooler kid that would say something like, “Oh, you’ve only found the first star level? Me and my cousin just beat the whole Star World and got to this place called Special World.”

My typical response: “Whoa.”

In first grade, we were all years away from smoking weed for the first time, let alone experimenting with any type of psychedelic. Six years later, these one-upping conversations about playing Mario would be replaced by bragging about who’d done what drug first, or ingested the largest amount of a particular substance. But I think Super Mario World was altering our perception long before acid or psilocybin mushrooms.

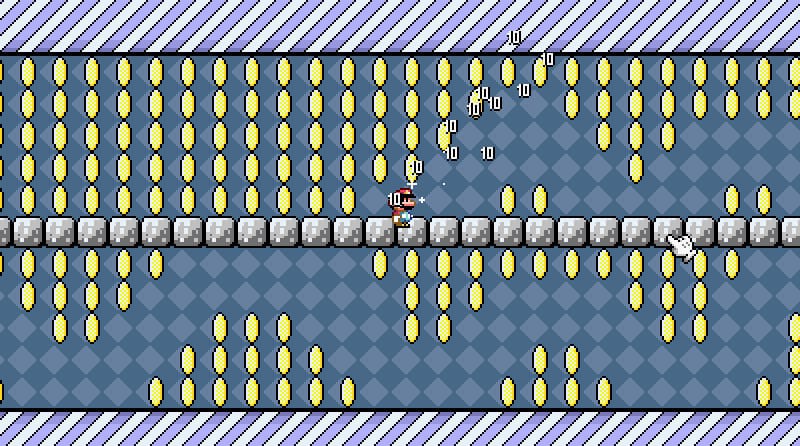

Consider the switch palaces. Transitioning from Super Mario Bros. to Super Mario World, suddenly here were these empty boxes, edged with dotted yellow lines. Playing the intro and first level of the game, I stared at those dotted-line squares and jumped through them, over and over, to see if anything would happen. When nothing did, I thought, What the hell are these things?

And then I discovered the Yellow Switch Palace. I felt giddy when I saw that golden dome, marked with a white exclamation point, sitting atop Kappa Mountain. On the map, Mario triumphantly raised his right fist as I selected the level. Upon entering, I jumped on the P-switch and manically collected every coin I could, feeling intoxicated by a river of that delightful chiming sound—ding, ding, ding in machinegun succession.

I then ventured through the green teleport tube, ran to the bulbous yellow switch, and jumped on it. A black rectangle appeared, saying, “ – Switch Palace – The power of the switch you have pushed will turn [blank squares bordered by dotted yellow lines] into [solid yellow boxes with exclamation points on them].”

Not quite sure about what this development actually entailed, I played the second level of Yoshi’s Island. Yellow blocks that harbored (to my delight) mushroom power-ups replaced the empty, dotted-line squares. I could now run across long platforms of these blocks, or use them as stepping-stones to get to some previously unattainable ledge that would present me with the gift of a fire flower.

Looking back, I see how the switch palaces tear the fabric of the game’s reality. By simply hopping on a small dome, the player irrevocably changes the landscape of Super Mario World. Empty space becomes solid matter, and you can access new parts of the game. Within the blink of an eye, the world, as well as the player’s view of the virtual world, transforms. The switch palaces also underscore the fact that humans have built the Super Mario World universe, which, as a kid, was all-encompassing. They draw attention to how one push of a switch—one small modification in programming—can alter the entire game. Thirteen years later, I’d discover that LSD could similarly expose sediment layers of reality that I didn’t previously know about, thereby changing my perception in both immediate and permanent ways.

They draw attention to how one push of a switch can alter the entire game.

Finding the other switch palaces (green, red, and blue) and changing more vacant squares into concrete boxes was also amazing, but, for me, the other major mindfuck in Super Mario World occurred after I finally made it through the exceptionally difficult levels in Special World: Gnarly, Tubular, Awesome, et al. In case you need a refresher on your Super Mario World geography, Special World is only accessible via a secret Star Road that branches from one of the Star World levels. The eight stages in Special World get increasingly difficult, sometimes on an exponential scale, and, as a whole, they’re much harder than any of the regular levels. To get a sense of these stages’ difficulty, see the amazingly detailed Super Mario Wiki description of the final level in Special World: that endlessly exasperating, this-makes-me-want-to-pull-out-my-hair stage known as Funky.

The level is a tsunami of Sumo Brothers and Chargin’ Chucks, and I remember throwing my controller at the screen more than a few times when I tried to beat Funky for the first time. I was playing Super Mario World the year the game came out, so I didn’t have access to internet guides for help—just word-of-mouth tips from other kids.

But the payoff surpassed anything I could’ve imagined.

I emerged from Funky battle-weary, with tired eyes. I’d been fixated on the TV screen for hours, and, if Mario could’ve reflected how I felt, he would’ve been tottering. Instead of taking me to some kind of epic new world, which is what I expected, beating Special World just transported me back to Yoshi’s Island. But this once-lush and green environment had deteriorated into sickly brown plains. The season had shifted from summer to fall, and this was only the most superficial transformation.

I played the level at the bottom right of Yoshi’s Island, curious about other wonders that might greet me. Where there was once a gang of standard Koopas—their yellow heads and green shells a comforting constant through every Mario game—walking across a small plateau, menacing, blue-booted foes with facsimile Mario heads affronted me. For a split second, I questioned whether this was real, or if it was some strange hallucination borne of playing Nintendo for way too long. (This uncertainty about what was or wasn’t real would later become a staple of my psychedelic experiences.) And then I jumped on one of the brutes and used its/my head to bowl over the remaining doppelgängers.

My reaction: “Whoa, this is weird.”

By the next day, I’d played through all the main levels to see what else had changed during the shift of seasons. To my dismay, the familiar Piranha Plants, which, like Koopas, had become the videogame equivalent to comfort food for me, were replaced by jack-o’-lanterns with grisly grins carved into their faces. The Koopa Paratroopas, who can jump and hover with the help of their cute white wings, had been supplanted by Mario-headed monstrosities with wings where their ears should’ve been, like some kind of grotesque genetic experiments. During my first LSD trip, I watched people take on reptilian qualities like sharp teeth and darting tongues with the same feelings of terror and wonder that I experienced when I originally encountered these deconstructed enemies from Super Mario World.

As with the switch palaces, the variations that accompany the transition from summer to fall in the game allude to how this universe can be dismantled. After passing Funky, a switch is engaged that defamiliarizes the game, which directly illustrates the fluid and high-speed nature of programming. As a seven-year-old kid, Super Mario World seemed like a perfect creation, but these meta moments showed me the underlying scaffolding, revealing the game for what it was: a human construct.

It’s been a long time since I’ve ingested acid or mushrooms. Now, tripping would likely be much more anxiety-ridden than it was during my late teens and early 20s. But my psychedelic experiences have stuck with me. While tripping, I started to understand music in much more nuanced ways, which changed my life as a musician. Acid helped me break down complex sounds and rhythmic structures into more palatable parts, and I realized that music, as with any other art, can always be unraveled if you look at it closely enough.

Although I couldn’t articulate it at the time, the perceptual shifts I experienced while playing Super Mario World as a kid accomplished something similar: they provided glimpses of the game’s architectural quilt. Before, I tended to see videogames as flawless, almost-otherworldly creations. Afterward, I like to think that, even as I got completely enveloped by other games, I always had an inkling that I was losing myself in a human-built, and therefore imperfect, universe.

///

This article is part of Mario Week, our seven day-long celebration of the 25th anniversary of Super Mario World and 30th anniversary of Super Mario Bros. To read more articles from Mario Week, go here.

First image by Andy Roberts via Flickr. Third image by Mario Arruda via Flickr. Fifth image by Jack via Flickr. Header image created by Hana Khalyleh.