The Technical Challenges of Virtual Reality

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel.

Imagine walking around and whenever you move your head, you feel dizzy. And soon you become nauseous. This was a common occurrence in the early days of virtual reality. It just felt wrong, what the VR industry calls “simulation sickness.” It is the result of using a headset on a computer that can’t run the software smoothly.

With quality virtual reality headsets due to be released later this year, the tech world is abuzz with the promise of VR. The hope is that you won’t just see fantastical games, but walk around in them. That sensation of getting lost in a game has lead to the rise of another buzzword: “presence.” Oculus described presence as “the unmistakable feeling that you’ve been teleported somewhere new. Comfortable, sustained presence requires a combination of the proper VR hardware, the right content, and an appropriate system.”

Believable experiences in VR come at a price. It has taken Oculus, the company at the forefront of the revival of VR, years to get the headset and its accompanying software just right. And to run the Oculus Rift headset properly you will need a substantial computer. Such a PC may cost around $1,000 when the Rift launches in early 2016. Here’s what Oculus says are the minimum requirements:

- NVIDIA GTX 970 / AMD 290 equivalent or greater

- Intel i5-4590 equivalent or greater

- 8GB+ RAM

- Compatible HDMI 1.3 video output

- 2x USB 3.0 ports

- Windows 7 SP1 or newer

To understand why these specs are needed, one has to know how virtual reality is different than normal software. Picture a game running on an HD monitor; this has aa resolution of 1920 by 1080 pixels. For VR, that screen would be cut into two halves, each brought up close to an eye, with a combined resolution of 2160 by 1200. This picture occupies most of your peripheral vision, which means it has to show more virtual objects than a game on a normal screen. And it is a stereographic image, running twice, once per eye.

The other issue is that VR has to be smooth, so when you move your head, the picture reacts quickly and believably. While television shows are shown at 30 frames per second and some console games can run as high as 60 fps, the Oculus Rift runs at 90 fps to make the virtual world feel seamless.

Palmer Luckey, the founder of Oculus, told us, “The reality is that VR is more demanding than any other type of gaming we’ve ever had. When you are trying to do 90 frames per second, stereo 3D, over-1080p resolution, and have a very wide field of view at the same time? It’s just a lot of things to stack on top of one another.”

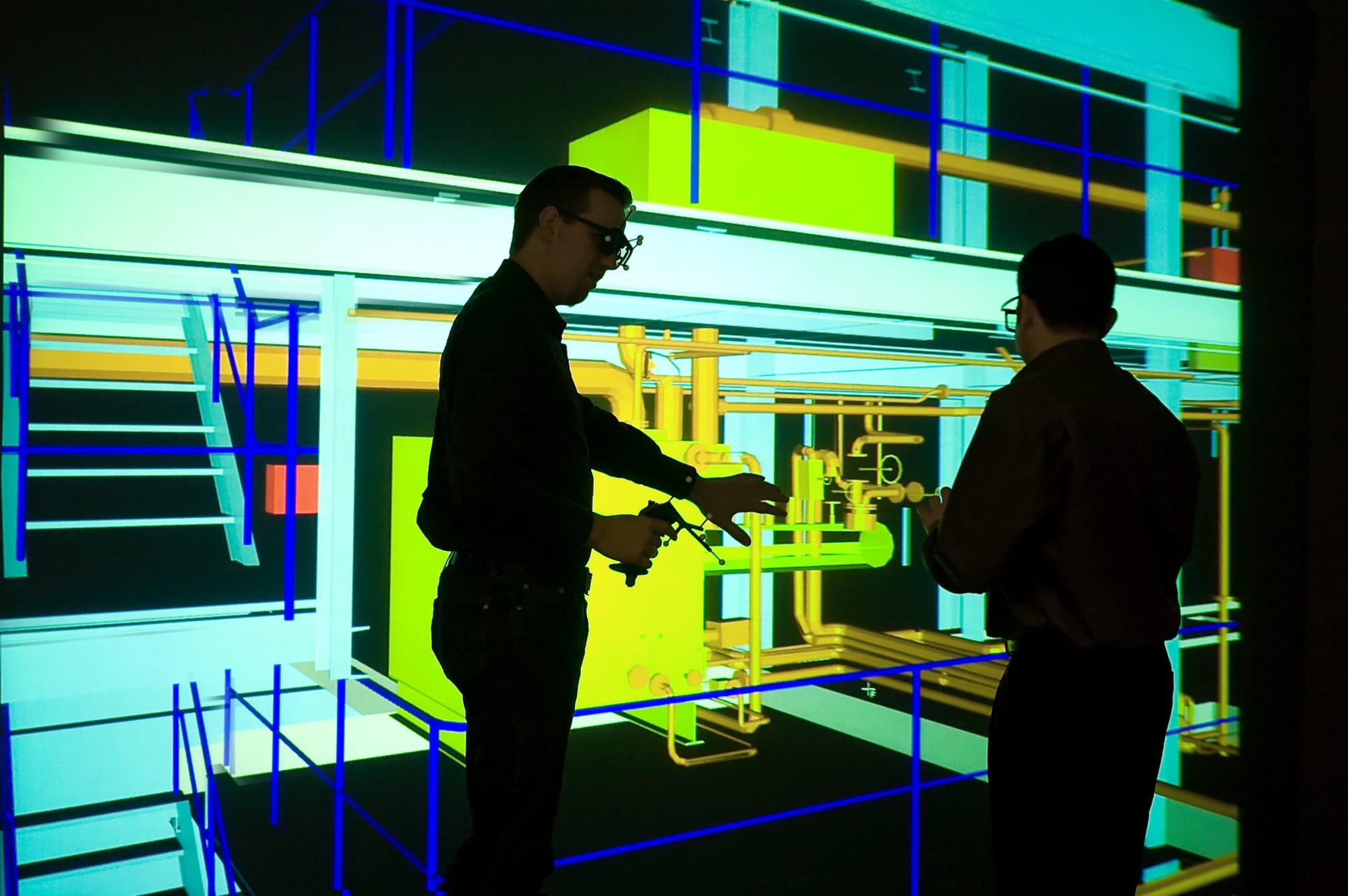

The result is an immersive game, but it is taxing on your computer

While your computer runs these extreme graphics, it also processes data from the movement of your head and body (picked up by a camera sensor), 3D audio that adjusts to your movement, as well as input from controllers. The result is indeed an immersive game, but it is taxing on your computer. And if you don’t have a PC that’s up to it, the picture jumps around, resulting in simulation sickness.

Kim Pallister, Director of Content Strategy for Intel’s Visual Computing Group, says, “If you are doing a simulation on a 2D monitor and you are bringing it to VR, you are going to up the performance requirements by a factor 1.4 to 2x. It varies a lot based on the the headset. There is no doubt that it raises the requirements significantly.”

Oculus and its Rift headset will have some competition. From HTC’s Vive to Razer’s OSVR, some will be more powerful and some will be less. And they all will have to worry about the performance needed for effective virtual reality.

But the content of the actual games also matters. In VR, you can lean over and look at something up close. Such scrutiny requires better graphics to be believable. You have to be able to see the hairs on a dog. Also, graphical tricks used in the past—like using flat 2D images to provide set dressing like grass—become obvious when you are seeing them in a 3D picture up close. So developers have to avoid shortcuts and make VR worlds quite detailed.

Also consider that the specs that Oculus released are only the bare minimum requirements; some games will push the graphics even further, requiring PCs that scream. But it isn’t all doom and gloom. Computer prices go down. Oculus is working with graphic card makers Nvidia and AMD to improve VR image processing. Microsoft has tweaked Windows 10 for VR, with Oculus Rift being recognized without any hassle. (Previous versions required a good bit of tinkering.) And Intel is doing research into how some of the heavy lifting that the GPU does can be done by the CPU.

“this is also an experience that is going to couple with a pretty high-end CPU”

Pallister says, “For that first round of VR products, graphic cards are going to be one of the most obvious things in terms of system requirements, but this is also an experience that is going to couple with a pretty high-end CPU and that you won’t be able to skimp there much.”

VR is just starting. Just as cellphones get annual releases, companies will likely improve models every year or two. Resolutions will increase to 4K or more; motion controllers will come; eventually the frame rate will be increased beyond 90fps. Much of this processing will require a more powerful CPU. PC hardware will have time to improve in both power and cost.

But with its high requirements, the first headsets released will be more priced for early adopters. “It’s just the reality of things,” says Luckey. “People have said, ‘You need to buy a PC? That’s too expensive! I’m not going to do that.’ Okay. Then you’re not going to participate too much in this first generation of VR. VR is going to go down in price. Computers today that cost thousands are going to be Black Friday specials for $200 in a few years. But that’s not today.”