The class war and canapes of HITMAN’s Paris debut

I’ve been to my fair share of parties. I don’t mean the plastic-cup-and-pizza apartment hang-outs, or the police-baiting all-night warehouse raves—I mean vaulted ceilings, black tie dress code, and free champagne. Parties where I leant on neoclassical statues while distant arty bass droned on, where tungsten yellow courtyards were transformed into ice-white future bars, and fountains and conversation tinkled nearby. I mean exactly the kind of party that HITMAN offers up for its opening act. It’s a party that is so familiar, in fact, that I was met with an odd sense of deja vu as I wandered through the grand doors of its fictional Paris Museum and into its predictably ornate lobby.

It’s a sense of familiarity that’s not just about the starched shirts and tromple l’oeil, but the sudden sense of aimlessness that greets you when you enter one of these events. You see—and here’s the secret—there’s nothing special about those parties. I mean, there’s the fancy canapes and the free champagne (did I mention that already?), but in reality they operate in a kind of holding pattern. Waiters circulate, guests mingle, drinks flow, and everyone gets bored. I was once shuffled into a vast baroque hall beneath London’s Savoy with hundreds of actors, producers and directors, and couldn’t help but feel I was attending the equivalent of a sports-hall school disco—a big open space territorialized by different social groups; classes and networks that are completely impregnable to someone like me.

This is your playground, these are your toys

That’s because I was always an outsider, finding myself at design events or West End openings where everyone knew the rules of engagement already. What I quickly learned was how to become a chameleon, how to mingle with a purpose. It might be stalking that waiter who brings the good canapes, it might be spotting a Game of Thrones star, or even just listening into the most tasteless and comical conversation you can find. You get to learn the room: That’s where HITMAN comes in. IO Interactive’s bald and barcoded sociopath has always been the ideal outsider, able to dress to fit any occasion, infiltrate any room and walk with the purpose of someone who knows exactly what they are doing.

This first episode of the new HITMAN plays the role well; a grand party simulator, the fantasy of a social chameleon, a masterclass in mingling with a purpose. Let’s forget about the inevitable murder for a minute, and focus on the party. This is not a typical videogame room of repeated guests and bad music-library techno; this is event-industry standard, with all the ebb and flow you would expect. There is the arty bass, the statues, the glowing bars and the pleasant gardens. There are caterers, security, waiters, and stylists. And most importantly there is the flow of politics and people, those trying to chat each other up, and those trying to catch each other out. Layered on top is a wonderfully old-fashioned world of spy novel mystery: back room deals and secret meetings, assassination plots and shady characters. All of it in an elegant vertical organization, from the tired staff idling in the basement break room all the way up to the sunlit galleries that house an auction of international secrets that Spectre (2015) would be proud of. This is your playground, these are your toys. Hunt waiters in the wine cellar or Shiekhs in the study, or just get distracted listening to the rich idiots talking shit to each other.

That basement break room was almost painful to me. Painful because I’ve been there, on that side, propping up the party. I’ve stood in the corners of beautiful rooms with my hands behind my back and watched my entire evening’s wage being eaten by a besuited man in a single bite. I’ve slumped in an airless basement during a 10 minute break, wondering if I have enough time to cram down the supermarket sandwich that’s been sweating in my bag all day. That’s why, when I walked into that basement, I couldn’t help but feel sorry for the ragtag group of service staff parked there. And when I heard some rich douchebag tearing the valet a new one about the care of his prototype sports-car he was the first on my hit list. One proximity bomb later and Leopold and his precious car were smoking among the privet hedges. Meanwhile, I was on my way out the gate, strolling along a Paris street, thinking about my first beer of the evening.

Yes, this is an assassination game, and I’d be lying if I said there wasn’t an element of class war to its details, encouraging you to elegantly or comically spoil the days of the rich and famous. Even more satisfying is the fact that my self-motivated hit on Leopold has also marked him as a possible contract for any other players of the game, meaning that he can expect to die over and over in ever creative ways for his somewhat meagre crimes. Hey, what can I say, he had it coming. They all have it coming in the end. HITMAN’s staggered release schedule that sees one location per month being released encourages players not to simply shoot through the story, but to run and re-run this particular party, to learn the patterns and routines of the entire cast of named characters, and ultimately murder them. It certainly seems like an event dense enough to support this style of play. Especially when the hand-crafted “elusive targets” start emerging— one-time-only hits that require the player to ID them from a picture and then assassinate in any way possible. A bodged attempt means they escape forever, while success brings unique rewards. Specific challenges offer expansion too, allowing you to start, say, on an elevated position with a sniper rifle, or already in disguise at the secret auction.

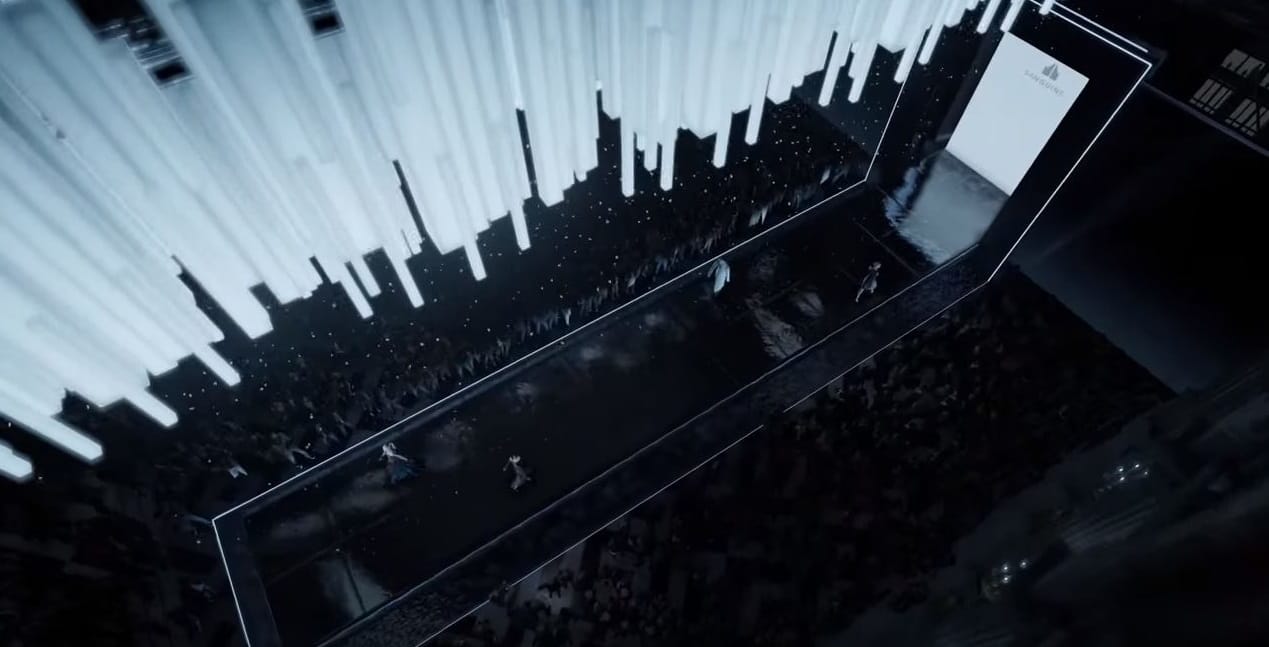

Yet, while this may form the main attraction for some, I can’t help but reload the level again and again just to revel in the textures. From the club atmosphere of the catwalk to the constant activity of the backstage, there’s a magnetic quality to everything going on. And as I tail one character or another, there’s a sense of power and freedom that begs my return. And whether it’s rat poison in the wine glass, an explosive on the chandelier, or a well-placed shot that sees a body bag being dragged off-stage while a fashion designer attempts to get on with his speech, it is all brilliantly reactive. Even when the AI goes off the rails, and Collateral (2004) becomes Weekend at Bernies (1989), the resulting silliness feels authentic to the idea of an assassin looking for a reason to kill. Any reason at all. But my finest moment had nothing to do with leveraging my “particular skills” over a carefully selected billionaire. Instead, it involved masquerading as a similarly bald and stern looking supermodel and taking the catwalk. The roar of the crowd, the applause, all just for walking down a strip of fancy stage, looking down on everyone there. What a turn of events, I thought, from outsider to everyone’s hero. It seemed the true fantasy of any party guest: to be the center of attention for a moment, before fading back into that ever shifting crowd of anonymity.