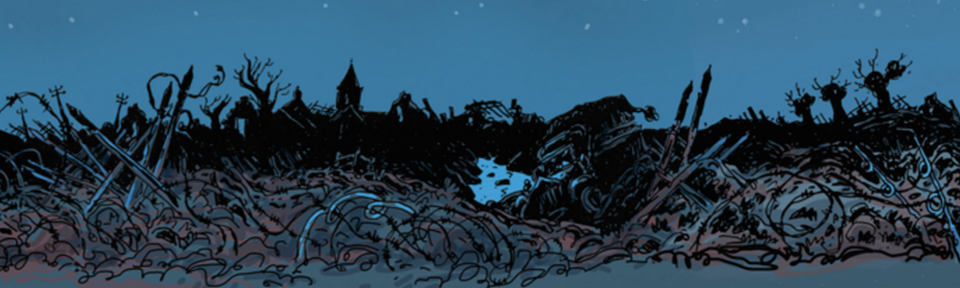

The Dismal Western Front of The Grizzled

The First World War is often referred to as The Great War, due to its immense scope, as it incited all the world’s national powers and resulted in a devastating death toll. Set within this war is the tabletop game The Grizzled, which makes no attempt to capture such scale, and instead hones in on a small squad of French soldiers whose camaraderie is their greatest chance for survival. In this, The Grizzled prompts comparison to Erich Maria Remarque’s 1929 novel, All Quiet on the Western Front, which describes the war through a concise and emotional narrative. The story follows the young Paul Bäumer and his squad of fellow volunteers of the German Empire. Like players in The Grizzled, Bäumer only manages to survive the war’s dangers by the love of his comrades and their distant hope for peace.

Like the novel it evokes, The Grizzled is a brief and straightforward experience. Each game is comprised of Missions in which players overcome Trial cards that are placed in the center of the playing field, known as No Man’s Land. Doing so activates Threats, and when No Man’s Land contains three identical Threats, the Mission is failed. It’s a cooperative game of “press your luck” in which players must safely empty their hand of Trials or withdraw to the cover of the trenches in order to succeed the Mission. Peace is ultimately achieved if the squad can overcome the deck of Trial cards before their collective Morale is depleted. This, like Remarque’s tale, establishes a harrowing tightrope walk done in tandem—as failure and success are collective fates.

The wartime horrors confronting Bäumer are rarely actualized as enemy soldiers. Instead of people, he is pitted against deadly devices and circumstances set forth by the machine of war. Due to their unrelenting breadth, these monstrosities create an inescapable environment of terror. For soldiers, the war is a world unto itself—a place where civility is foregone for animalistic survival. Of course, the decrees of politicians and the iron sights of marksmen are behind such evils, but Bäumer’s fragility cannot comprehend their humanity—and so he concedes, “We have become wild beasts. We do not fight, we defend ourselves against annihilation. It is not against men that we fling our bombs, what do we know of men in this moment when Death with hands and helmets is hunting us down.”

Threats in The Grizzled are characteristics of a similar milieu—battles of survival rather than head-to-head conflict. The game features no depictions of enemy soldiers brandishing bayonets. Instead, Threats are incorporeal in their origin, and break through grim skies with callous inevitability. Between these tumults there are restless days at the Front whose quietude force soldiers to wallow in their stark circumstances. Bäumer’s demons swell in such moments, “Night again. We are deadened by the strain—a deadly tension that scrapes along one’s spine like a gapped knife.” The Grizzled finds its rhythm in this sense of impatient anxiety, through which players crawl towards peace and risk safety in the frantic sprint towards victory.

Bäumer only manages to survive the war’s dangers by the love of his comrades

The Grizzled further captures this volatile setting with the illustrations of Bernard “Tignous” Verlhac—one of the many cartoonists and journalists tragically killed during the Charlie Hebdo shooting in January of 2015. In addition to his satirical illustrations for the fearless Charlie Hebdo magazine, much of Tignous’ career was motivated by activism. He belonged to Cartooning for Peace, an organization whose work promotes the education and awareness of topics such as women’s rights and censorship. Tignous also illustrated for the French affiliates of the World Wildlife Foundation and Clowns Without Borders. During a eulogy at her late husband’s funeral, Chloe Verlhac showed her belief in the importance of his work and praised cartoonists as “messengers of hope.”

In Tignous’ depiction of the First World War, this hope is one encumbered by colors of rust and rainy earth that all melt together and create a static mess of scenery. He paints the inescapability articulated by Remarque, “Everything is fluid and dissolved, the earth one dripping, soaked, oily mass in which lie the yellow pools with red spiral streams of blood and into which the dead, wounded, and survivors slowly sink down.” Those survivors, the Grizzled themselves, embody a grey reluctance with sapped shoulders and tired eyes. The game’s instruction booklet features a special thank you to Tignous, which characterizes him as a dear friend to the game’s creators. Readers are left with the words “Hasta Siempre Tignous,” a faithful phrase that suggests his work will be everlasting.

In addition to Threats such as frigid snow and mustard gas, which hinder all players equally, The Grizzled challenges players with Hard Knocks. These Trials capture the psychological horrors of war by forcing individual players to act irrationally, as they are overcome by frenzy and phobia. Such traumas take place on the periphery of Bäumer’s tale, like a toxic tide that washes through and floods the trenches, sweeping its victims elsewhere while leaving survivors muddy but still fit to fight. The violence that remains is in watching these stresses develop and linger before a helpless Bäumer: “One of the recruits has a fit. I have been watching him for a long time, grinding his teeth and opening and shutting his fists.” It is in coherence with these words that Hard Knocks are festering wounds, which must be dealt with collectively.

Amid such mental desolation, Bäumer’s only true comfort is the solace of his fellow soldiers. Even while lost in No Man’s Land, the mere sound of his comrades, familiar noises cutting through a wasteland, have the ability to lift him up above isolation. Amid despair, they prove to be invigorating— “They are more to me than life, these voices, they are more than motherliness and more than fear; they are the strongest, most comforting thing there is anywhere: they are the voices of my comrades.” Here too, in the words of companions, players of The Grizzled find some reprieve. Players may support one another through the difficulties of Hard Knocks, but they are unable to mend their own wounds. This interdependence is what drives The Grizzled, as the game grinds to an isolating halt when the team fails to communicate.

Bäumer and his squad mates, like those in The Grizzled, trudge through these motions of war like those confined to a chain gang—enslaved and bound to ill-fated neighbors. Their story isn’t one of particularly remarkable heroism, navigated by catastrophe or skill. They are not written into the forefront of iconic battles, nor are they described with great marksmanship or fortitude. Bäumer and his friends are vulnerable captives—“We are little flames poorly sheltered by frail walls against the storms of dissolution and madness, in which we flicker and sometimes almost go out… Our only comfort is the steady breathing of our comrades asleep, and thus we wait for the morning.” And so they do what little they can, clinging to one another for safety in the hope that chance will see them through.

the game grinds to an isolating halt when the team fails to communicate

This sense of hope through camaraderie is that of orphans bound by abandonment. It is not only that these soldiers are lost in a horrifying situation; it is also that they have no home to which they may return. Upon taking a brief leave, Bäumer has difficulty reconnecting with his family and hometown. As if they have betrayed him, or he betrayed them, there is a palpable discomfort in their reunion. His family members only fill him with sorrow, his neighbors fill him with contempt. He sleeps in his childhood bedroom as if a ghost, held within familiar walls but unable to feel anything at all. By the end of his stay, he regrets ever leaving the Front, for it has destroyed any wild dreams he held for normalcy after peace. Bäumer is alive, and so the war has not yet taken his future. Perhaps worse, he suffers the wretched fate of having been robbed of his past.

Among the solemn visual art of The Grizzled are two group portraits, which encapsulate such sentiments of irrevocably tainted innocence. At first glance these illustrations appear to show one squad of soldiers separated by long years of war. But peering through their veils of cigarettes and scruff chins, one finds mere children no older then when depicted with bright eyes in overalls and news caps. Bäumer laments this loss after watching his first friend killed by the war, “Iron Youth. Youth! We are none of us more than twenty years old. But young? Youth? That is long ago. We are old folk.” Like him, those in The Grizzled are broken kids—clutching to boots and rifles as though they are nostalgic dolls or baby blankets emitting motherly pheromones. They are no tougher or wiser than the day they left their families at the train station back home. Still children, but children turned grey as they are devoid of life’s color, sticking together in spite of it all.