The inescapable echoes of Homeworld: Deserts of Kharak

It might have been the cruise missiles that triggered it. One of a string of upgrades nudged towards me by my commanding officer, charting the slow expansion of my carrier’s already formidable arsenal. It was the name— cruise missiles— that was so distant from science fiction, so connected to a sideshow of images of war. It would have been the 1990s when I first saw a cruise missile launch, the flashcut plume of smoke followed closely by the hammerblow of ignition—the camera whiteout as its automatic exposure struggled to account for the solid-fuel flare that drove the missile until it was a distant glowing speck, arcing over a distant amber land. That amber land was Iraq, and these projectiles landed there unseen by the cameras, the audible roar of destruction distant enough to follow a few seconds after the flash of a successful impact.

The cruise missiles of Homeworld: Deserts of Kharak take flight in much the same way, though from the elevated viewpoint of the game’s camera they seem distinctly more benign. Perhaps benign is how the developers at Blackbird Interactive saw these armaments when they added them to the vast aircraft carrier-on-wheels that serves as the player’s base of operations in Deserts of Kharak. And perhaps they are benign, perhaps it was the amber sands that triggered my memory, or the low drone of everyday military radio chatter. Perhaps it was even the talk of prophets and holy wars, the leader mounting a “sermon on the rock” clad in something that seemed to flicker between an industrial gas mask and a jet black veil. Whichever it was, the accumulation of those images pointed to something in particular, an aesthetic I was born into, something unnervingly familiar.

It was war as I knew it, distant, technological, baked in desert heat, waged on desert sands

It was war as I knew it, distant, technological, baked in desert heat, waged on desert sands. It was the idle dialogue of my forces, all call signs and denotations, which brought to mind the lazy discussions that ran under every leaked video of a drone strike. It was the word “coalition”, used so casually to describe the loose alliance of forces that seemed to stick in my head like a grain of shrapnel, an annoying itch. Hadn’t I been here before? Not on the distant planet of Kharak, not among these fictional races and their squabbles, not beside these improbably vast machines of fantastical war. But here in the desert, watching towering plumes of smoke emerge from impact sites while my quietly idling armored assault group issued a faintly audible complaint over the radio channel, “I can’t take it.” he whispered “it’s too damn hot”. Haven’t we all been here? Here, hovering as a distant observer, staring at a screen, hunched forward in the short winter days of January.

///

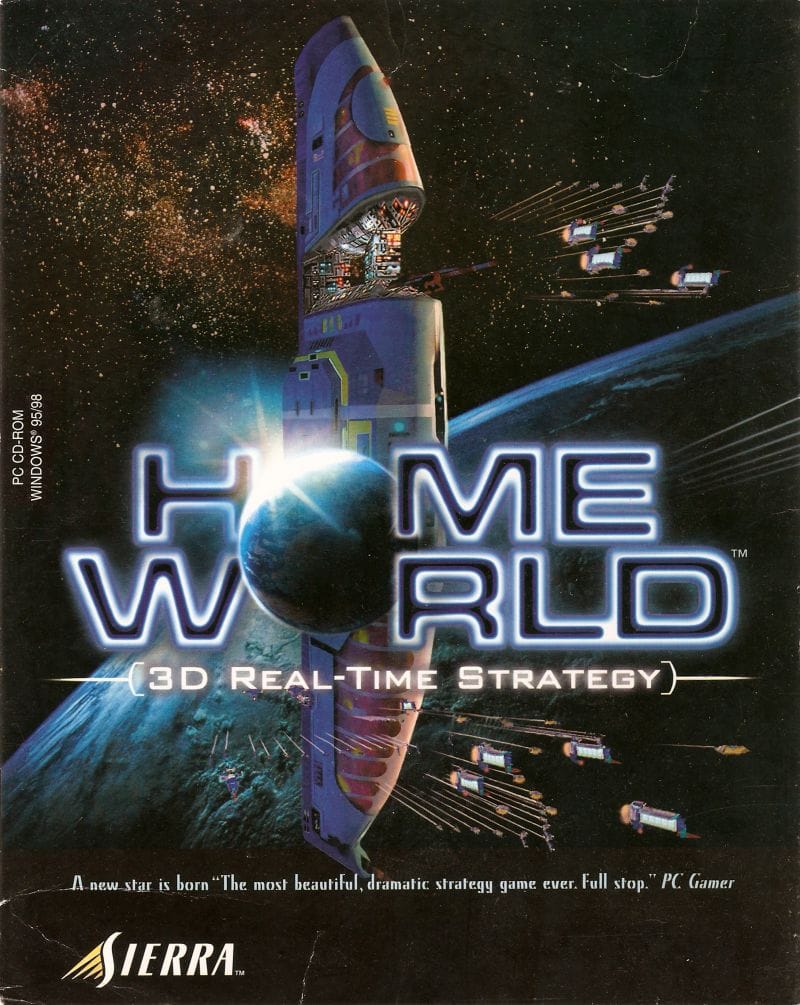

Many would have played the original Homeworld as bombs fell on Iraq. In 1999, bombings could sometimes be a daily occurrence, with more than 100 airstrikes targeting the northern no-fly zone. This campaign would invariably be in and out of the news, but would be ever present, the desert and the accompanying plumes of smoke, the military chatter and targeting overlays. There would be the occasional computer generated simulation, as crude vehicles and the brash arrows favored by news agencies crossed paths. That conflict, and the interstellar war at the heart of Homeworld, could not have felt further apart. Homeworld was a 70s Chris Foss book cover: patterned ships set against glowing nebulas, shimmering space battles of unprecedented scale. It was less a war and more a space opera, a grand journey built on complex three-dimensional strategy. Its story, that of a race of exiles pursued through space by vast forces, in search of what was once their home, seemed to borrow from grander sources than games of the time were used to. Anabasis, by greek soldier and writer Xenophon, was chief among them, charting as it does the march of 10,000 mercenaries from Persia back to the relative safety of the Black Sea’s shores in 401 BC. This ancient work has come to represent an inspiration for countless stories, and in Homeworld’s case it formed the backbone for a campaign where each unit persisted across escalating missions that headed deeper and deeper into the unknown. This ancient influence is not only evident in the game’s structure, but in its naming conventions, which mirror ancient Middle Eastern and Asian tribes.

The 2003 sequel, Homeworld 2, only furthered these connections, focusing more on the deity of Sajuuk and the conflict between the tribes that believed in his power. Only months before, the first coalition forces had entered Iraq, their long road to Baghdad filling news broadcasts with amber lands and mechanized war, columns of tan vehicles rolling out across deserts that stretched to the horizon, punctuated by the black smoke of burning oil fields. Once again, Homeworld 2 might have offered something of a respite in its starward vision, its colorful explosions lighting up distant voids. Yet on the columns rolled, and on the cameras rolled, and the images of a desert war flickered in the background whether you were watching or not. That journey into Baghdad has also been compared to Anabasis, not least in The March Up: Taking Baghdad with the First Marine Division, published as one of the first full accounts of the invasion in the following year. Written by Bing West and Major General Ray L. Smith, it recounted their experiences and the experiences of the division tasked with taking Baghdad. Both were military men, Bing West being a Vietnam veteran as well as assistant secretary of defense under Ronald Reagan, and from its first pages March Up reaches towards an epic mode, using Anabasis as a way to connect modern marines to the great warriors of old. Unlike Homeworld, which finds in Anabasis a grand and fantastical journey of desperate struggles, March Up finds the questionable glory of fearless combat, crudely recasting an invading force as warriors in search of a home.

///

Deserts of Kharak, though appearing over a decade after the original Homeworld games, once again finds structure in the journey of Anabasis. Setting the player on a journey across a great desert in search of a mysterious technology, it casts them and their carrier out into the sand, to forge a trail across dangerous lands. This is reflected in every aspect of Deserts of Kharak, from the persistence of units across missions, to the limited resources that force the player into careful restraint rather than the building of vast conquering armies. Adaptability, decisiveness, and tactical awareness are the qualities this journey asks for, not the machismo of overwhelming force, the arrogance of shock and awe. It is an effective translation, the space combat of the original games matched with ground-based analogs, the power relationship of small strike crafts, ranged armor and heavy cruisers still intact. The three axes of open space have been replaced by the bluffs and dunes of the desert, making line of sight and elevated positions key to making the most of a limited unit count.

ships no longer backlit by nebulae but buried in sand, corroding under scouring winds

This, in some ways, grants Desert of Kharak even more tactical detail than that of its forebears, where the topography of a battle mattered little. Yet, it is in its aesthetics that Deserts of Kharak most differs from its series, and these changes are what seem to bring the echoes of the world Homefront was born into to the fore. This desert land is inescapably connected to those grand campaigns that might lay claim to Anabasis, those desert invasions that are so unpleasantly familiar. It doesn’t appear to be a purposeful choice, but instead a kind of overbearing influence, one which has leaked into this world by exposure alone. In Deserts of Kharak those Chris Foss ships are no longer backlit by smoky nebulae, but are buried in the flowing sands, their bright patterns corroding under metal-scouring winds. The Middle Eastern inflected names and music no longer seem in service of an exotic atmosphere of space travel. The Anabasis is no longer that of a journey home, but of an “expeditionary force” striking out into lands unknown. All of these elements, even those that once could be thought of as defining aspects of Homeworld’s colorful space-fantasy, somehow conspire to evoke the history of war that has shadowed the series; echoes from another world, another time, rising to the surface.

Unpleasant as it is to accept, this association is a natural one for a certain generation. The symbol of the desert has become colored by conflict, those images of scorched sand difficult to forget. Deserts of Kharak is not to be blamed for unearthing these connections, for so easily slipping behind these images and trying to make them strange. There is some integrity in its detail, its precision, its distance. It manages to reach the epic mode, the grand narrative, to evoke a mythical journey now lost to us. But it also fails to escape the easy orientalism of that same myth, the simplicity of bloodless violence. It is a throwback in many senses, not just to the history of its own series, but to images of war that came to us already cold, already distant. To shots of cruise missiles launching but never landing, just glinting over that amber land.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.