The insightful history of one of the first modern board games

Though many people might think that board games are a relatively modern phenomenon, the likes of Trouble (1965) and The Game of Life (1960) were actually preceded by years and years of table-based entertainment, flung as far and wide as Egypt, India, and ancient China. A brief glimpse into this long and storied history is provided by the Grolier Club in New York and their exhibition The Royal Game of the Goose: Four Hundred Years of Printed Board Games. Curated by Adrian Seville, this exhibit interrogates the many different forms of “The Game of the Goose”—one of the first modern-style board games—between the 17th century and the present day.

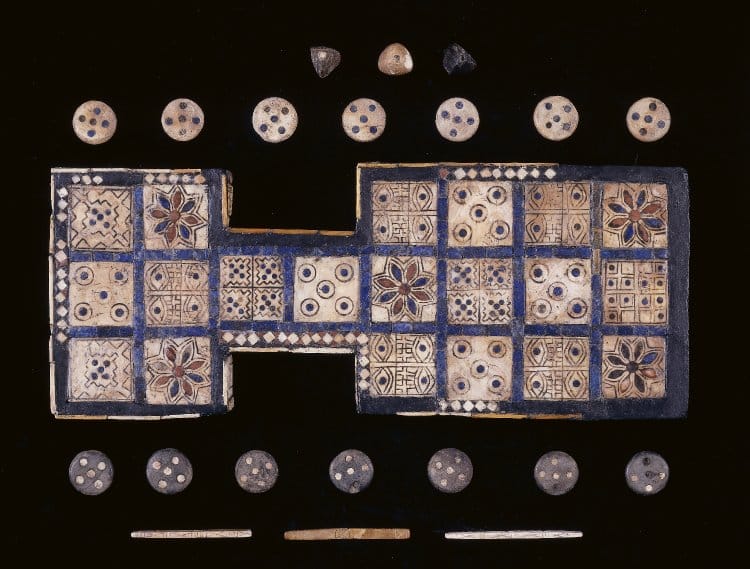

In predynastic tombs in Egypt that date back to 5,500 years ago, a game called senet was found, making it the oldest known board game ever. Successful senet players were thought to be protected by the gods, and the game was placed in their burial chambers for luck. A thousand years later, the royal game of Ur was played, and then discovered in tombs in Iraq by British archaeologists with tablets containing such detailed rules that the game can be replayed today. The game “Go” was mentioned in Chinese writings as early as the 4th century BC, and Pachisi—now Americanized and commercially sold as Parcheesi—may be a variant of Ashtāpada, a game that the Buddha famously refused to play in the 5th or 6th century BC. The viking game Hnefatafl was mentioned by medieval sagas as early as 400 CE, and played until the 1200s. Chess was modified to its modern version in Iberia by the 15th century. As early as we had civilization, we had games.

The Royal Game of Ur, via the British Museum

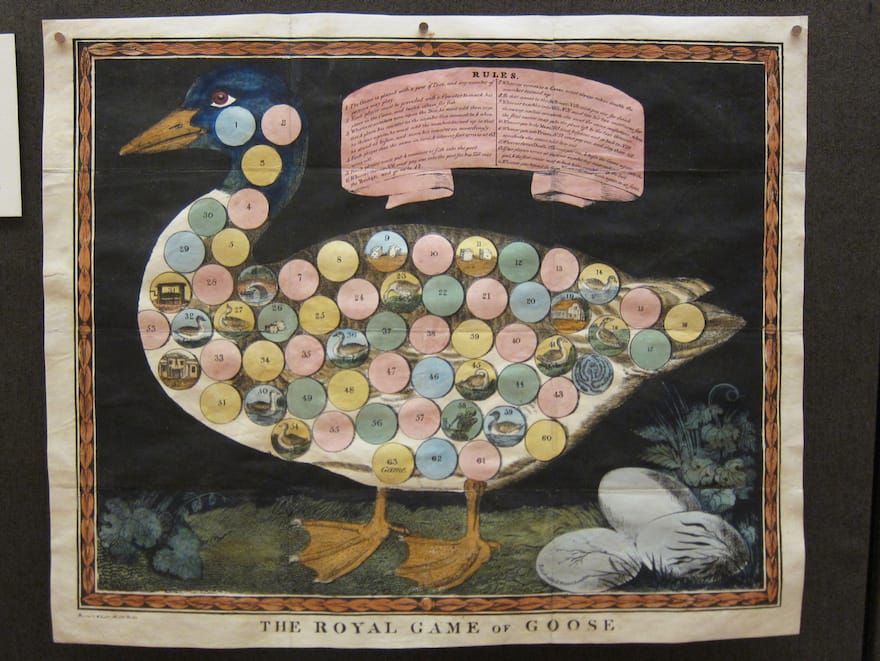

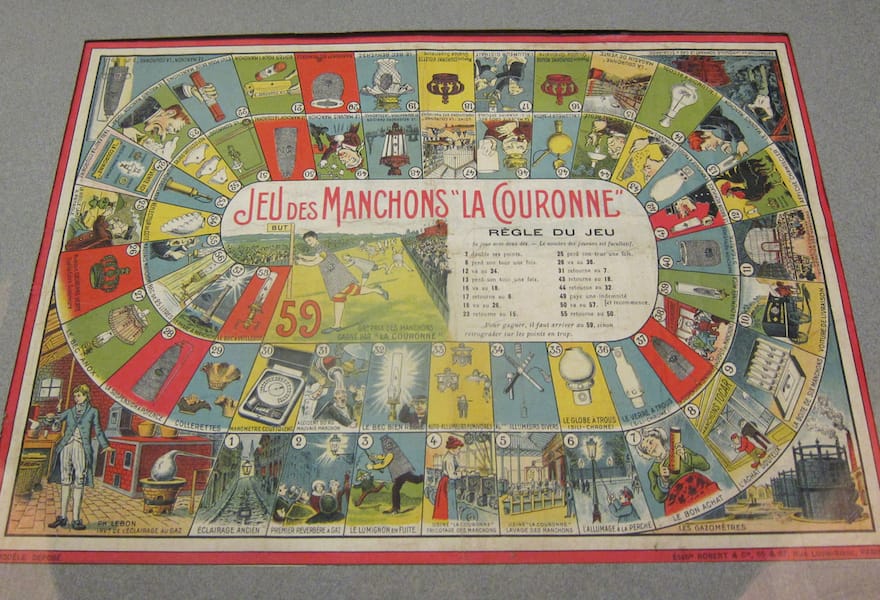

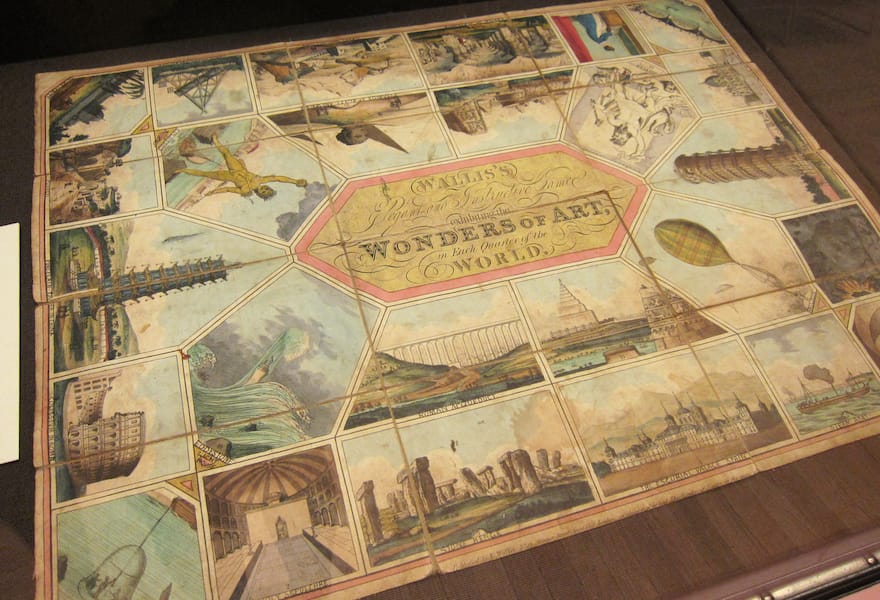

The Game of the Goose, the focus of Seville’s exhibit, was first recorded when Francesco dei Medici sent a copy to King Philip II of Spain in the late 1500s to wide praise. Since then, it has flourished in one form or another, and Seville’s collection includes copies that span from Germany to England to Canada. The appeal of the exhibit, however, is not just for history buffs. The main draw of the exhibit is the vast collection of boards, all presenting visually striking takes on the same basic concept. While certain game boards do present the eponymous goose, others wind their spaces around a snake, or fill them in with pictures of architecture or other amusements. They resemble illuminated manuscripts from the medieval era, or old illustrated children’s books; it’s hard to recognize that they’re all for the same game. Like senet’s tie to the afterlife or the way Go dealt with war, Goose said a lot about the society it was created in: the goose represented purity and luck, while the number of spaces (63) was meant to indicate tranquility and wisdom at the end of a life.

the Game of the Goose says a lot about the society it was created in

This continuity is even more apparent with a brief look at the rules of Goose: there’s one track with a varied number of steps, and the players each roll a die in an attempt to reach the end first. Sound familiar? It’s been a template for board games up until the modern day. Perhaps you remember the bright colors of Candy Land (1949) or the devious pathways of Chutes and Ladders (1943) from your childhood, or maybe you’ve gotten heated over a game of Sorry! (1929) one too many times. These modern amusements deviate in name and detail, but the boards are as winding and elaborate as those of Goose in 1640—and 1784, or 1820, or 1900.

In 1934 the game became a promotional maneuver for Coca-Cola, and in 1953 it warned of the ridiculous nature of Italian elections. By investigating the inspirations behind these games and their rules, we can learn a lot about the social climate of where and when they originated. Could the same not be said for us now? In 200 years a historian could discover the Target™ edition of Monopoly (1935) and display it proudly. Sure, it won’t protect us after we die, but it might tell that guy something about what we valued.

See “The Royal Game of the Goose: Four Hundred Years of Printed Board Games” at the Grolier Club in New York until May 14.

Header and additional photos by Claire Voon.

H/t Hyperallergic’s coverage of the exhibit.