About 30 miles northeast of the Frank Gehry-designed campuses and complexes where competing cloud environments are designed, there’s an Oakland museum full of game cartridges. You can see the sign from the highway: The Museum of Art and Digital Entertainment (MADE).

That the sign is visible from the highway is a big reason for an uptick in attendance since the museum’s February 2016 re-opening, I’m told, and this seems right to me. In the San Francisco Bay, where programming cultures abound and history is cast as something to be disrupted, forgotten, discarded, the MADE idiosyncratically contrasts the irresistible narratives playing out in the marketing and team scrums of nearby Silicon Valley.

I caught up with Anders Sajbel, the creative director for the MADE, who took me through the museum’s history, its future, and how the context of a museum might change the way these games are perceived and interpreted.

The MADE is a non-profit dedicated to the preservation of videogame history, and to educating the public as to how videogames are made. Its space is divided largely in two: the first, a display floor, arranges game consoles and cartridges in a roughly linear order by era. Most of the games and consoles were received by donation, the majority of those from the now-defunct GamePro magazine’s offices.

The second space is formed by a cluster of classrooms, in which seminars and workshops cover such topics as ‘Scratch Programming for Kids,’ the finer points of character design, and how to make your own GIF. When I visited the space, Anders was preparing it for a talk later that evening by a panel of sound designers whose game audio has appeared in the Ratchet & Clank and Oddworld series’.

there’s something to learn from the faded boxes and failed peripherals

The tacit interdependency of these two spaces is important to make explicit: by co-locating a space for game history with a space for learning how to make games, the MADE enables a dialogue about what’s come before and what’s coming next. This is where the context of a museum adds value, and elevates the concept of the MADE above festishism or nostalgia. In a city where ‘what’s next’ is valued in billions, the MADE presumes that there’s something to learn from the faded boxes and failed peripherals of yesteryear.

I recently moved to San Francisco, and moving all my stuff was surprisingly easy, because people don’t really have stuff anymore. All of my carefully curated collections of books and records live in the cloud now. If not for a duffel bag of wrinkled t-shirts, I’d have arrived empty handed. So you could say I was skeptical that the value attached to little grey cartridges might outweigh the incredible convenience of lightness.

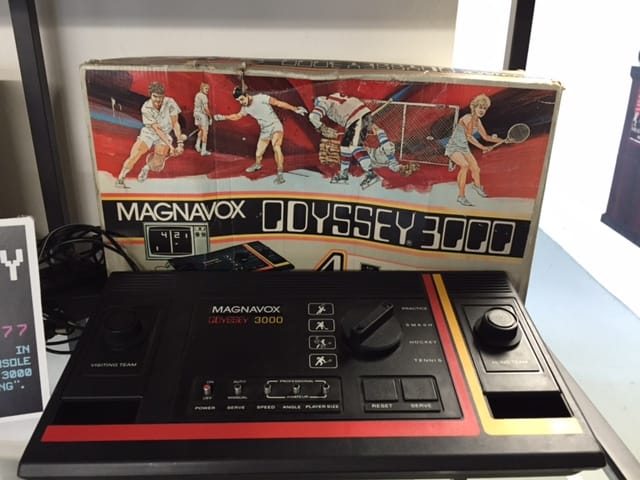

And then I saw a faded Super Nintendo Superscope box and, like Anton Ego eating ratatouille and being transported in his mind’s eye back to his childhood home, I was on maroon-colored carpeting in my parents’ basement, whiling away summer hours. A Power Glove presumed to sit in a glass case. Curiosities, like Philips CD-i’s with Nintendo-licensed characters, speak to oddball arrangements and one-offs in the history of the console wars. Stacks of old gaming magazines; the grey Game Boy display case from which one can sample bi-chromatic Tetris (1989); a cardboard standup of infamous Atari flameout E.T. (1982).

What struck me immediately was the power of the packaging. The MADE is a 1980 aesthete’s opium den.

What seems, when on store shelves, to be junky old marketing—crass, obnoxious, and silly—takes on a retrospective resonance. In that, the MADE serves to not only preserve and re-frame an aesthetic that existed between the late 1970s and late 1990s, but drives one to consider the design of the marketing encountered everyday.

The MADE seems to tap into the tactility of these consoles

What will retrospection do to, say, the celebrity-laden mobile game commercials that have currency today? Or, put more bluntly, turn an Odyssey 3000 box into a t-shirt and I might never take it off. In any other context, one might simply conclude that the MADE is possible because of an extremely lucrative nostalgia market that pumps out Transformers movies for young men who grew up on Transformers, and who today have jobs, but don’t yet have kids, and so have money to spend.

But then again, there are those nagging concepts of community—the beckoning classrooms, asking the visitor to not only experience videogame history, but then to apply it. There are the kids being taught programming, and the partnerships with local schools via youth education programs, providing job experience in exchange of volunteer hours. The MADE seems to tap into the tactility of these consoles to reinforce the value of physical community.

Like everybody in the Bay, the MADE is struggling with outrageous housing prices driven by the influx of the tech industry. Finding an open warehousing space to hold shelves of game consoles and cartridges is particularly challenging. One never knows if, when the lease is up, one will be forced out so that a building can be rented for twice the price, or sold off to developers.

But for now, the MADE is hoping to keep expanding. Anders is planning to expand the collection to include recently discontinued consoles, like the Xbox 360, and a themed exhibit dedicated to former Nintendo CEO Satoru Iwata. And the demand for spots in MADE classes continues to grow.

For those of us for who the Bay remains a dream space of abstracted values, future promises, and very real inequalities, the MADE is a grounding experience. Walking in this cemetery of former giants has a way of doing that.

Visit www.themade.org for more information about the museum and a schedule of upcoming events.