The Outsider Art of Dominions 4

In 1947, French painter and sculptor Jean Dubuffet coined the term art brut, or “raw art” when translated to English. It was used to describe, by his own definition, “Those works created from solitude and from pure and authentic creative impulses—where the worries of competition, acclaim and social promotion do not interfere.” He was interested in art made by people who had never graced the halls of art school, who shunned the company of fellow artists and drew no influence from popular trends. In an art world plagued by repetitiveness and inauthenticity, Dubuffet argued, only the work of those totally outside society could be truly original. Children and people with mental health problems topped his list of favorite artists; he was dedicated to the movement that would, eventually, come to be known as Outsider Art.

///

While the world of videogames is wider and weirder than it’s ever been, taken at a distance, a lot of it begins to look familiar. 2015, for instance, will likely be viewed as the year of the open-world role-playing game, with a smattering of the usual guy-shooters thrown in. Like any art scene, videogames are influenced and inspired by whatever’s being made and published in the same environment. This results in patterns, trends, and a lot of iteration of similar ideas—all natural things for a medium, and all things that Dubuffet despised.

Now, I don’t pretend to know what games a particular 20th century Frenchman would have enjoyed, but his definition of Outsider Art helped me understand one of the most enigmatic, mystifying games I’ve ever spent time in. The seeds for the first Dominions (2002) game were, as per Dubuffet’s qualifications, planted in solitude. Kristoffer Ostermann, one of the two creators of the series, was taking a 1000-mile hike through Spain and France. He had a lot of time, he writes in the Dominions 4 (2013) manual, to think. At some point over the seventy two days it took him to walk that distance, Ostermann conceived of what might be the most unapologetically complicated strategy game ever made.

As of writing this, I am in a multiplayer game of Dominions 4 with 13 other people, only two of which I actually know. I was invited by a friend, who I presume was also invited by a friend; word-of-mouth is the game’s most successful marketing strategy. Since there’s no dedicated single-player mode and matches against the computer feel a little too purposeless to be sustainable, big multiplayer games are where Dominions 4 really shines. That makes it all the more baffling that there’s no easy way to do this. Online matchmaking is non-existent, and there are no servers dedicated to actually hosting games. In our friendly match, the host is currently running two instances of Dominions 4 on his computer—one to host the game, and one to actually play. For some reason, you can’t do both in a singular effort.

THE MOST UNAPOLOGETICALLY COMPLICATED STRATEGY GAME EVER

Turns happen simultaneously, about once a day after everyone has plugged in their orders. It’s closer to play-by-mail chess than most modern videogames. This match will be over in several weeks, give or take. By then, plenty of people will be knocked out by the deadliest enemies of all: frustration, monotony, the many-faced duties of adulthood, and the siren call of other, simpler games. I imagine I will not be among these lucky few as my time in this game is looking to be briefer, and a good deal more violent. To explain: I began this game in an unfortunate situation. While I’ve played about 20 hours of Dominions, the player to my east has spent over 200 hours in the game. Doubly worse, I have no idea what he’s capable of. He was playing Patala, a faction vaguely based on mythology concerning the Indian underworld. I knew he had snake people and monkeys at his disposal, but I didn’t know what the hell monkeys or snake people could do. I had never encountered or even heard of them up until then. This is a big problem for me. To take a detour in service of my point, here: MMA is, by many people, considered the most difficult sport in the world. That has more to do with its complexity than physically punishing nature—fighters pick their focus considering their own weaknesses and those of upcoming opponents, since no one has the time or talent to learn it all. A similar principle holds in Dominions 4. The person with the most knowledge (or time to acquire it) usually triumphs, but I’ll go ahead and say it’s practically impossible for any one person to know Dominions 4 inside and out. That includes, amazingly, the creators themselves.

Much of the development of Dominions has been additive. The first Dominions game was released in 2002, and the creators at Illwinter Game Design have been adding features to the game in one form or another for over a decade. It’s gotten to the point where even they don’t remember what everything does. “There are countless rituals, combat spells and other special abilities in the game,” said Johan Karlsson, the main programmer on the two-man team. When he says countless, he literally means that they aren’t sure how many there are. “I’m actually surprised by what some things do now and again, even though I programmed it.”

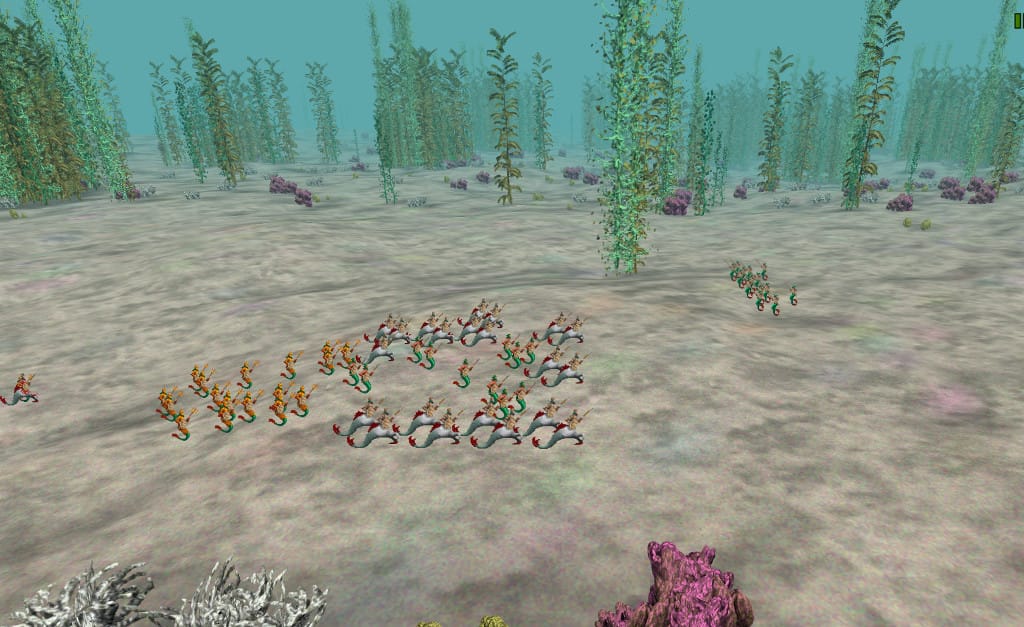

The driving design principle seems to be content above all else. It’s spelled out on the Illwinter website: “Animation sequences are intentionally kept simple to allow us to stuff more monsters and spells in the game than any other game, except possibly a roguelike. They don’t have any graphics for the monsters after all,” reads two of the four sentences in the meager ‘about’ section. Of course, doubling down on content above all else is hardly breaking rank in the world of game development, but the sheer quantity and way in which those things interact, somehow pushes Dominions into an oddly magical kind of territory.

I still remember one of my first games of Dominions 4. I was playing the relatively beginner-friendly nation of Abysia. I had mopped up in the early game, claiming vast swathes of territory with my army of lava people, who were well-armored and damaged the soldiers of other nations by proximity alone. I had backed one player into a mountain range and prepared to finish off his remaining troops. Then it started to pour. He had cast a spell summoning a storm and, drenched in cold rain, my lava people got a lot less dangerous. The best part was, I had no way to know that spell would interact with the Abysians in that way. It’s entirely possible that my opponent didn’t know either, and were just favored in their experimentation. In its fourth incarnation, Dominions has over 1500 units, 600 spells, and 300 magical items, and it doesn’t give a shit whether or not you ever see them. There’s never been a tutorial for the game. When I asked why that was, Karlsson said that “it would take time to implement. I would much rather put that time into making some new rituals or something else that makes Dominions a larger and better game.”

CONTENT ABOVE ALL ELSE

It seems almost compulsory the way Illwinter continues to pack new things into the game. But why was that their approach in the first place? From talking to the pair at Illwinter, it seems as though they created Dominions so that they could play Dominions. “It’s just obviously a good thing,” said Karlsson about the neverending firehose of content he’s been spraying into Dominions for over a decade now. “I always like to discover and try out new units when I play a strategy game.” Much of the theming of the game’s nations, from the Mayan underworld Xibalba to the Nordic Vanheim, seems to also be pulled more from personal interest than any other considerations: Ostermann, when he’s not making inscrutable strategy games, is a professor of Religion and Mythology.

Dubuffet’s vision of art brut was not art made in the style of art, but art that came from something untouched by culture or society within the artist. More than anything else, this is what cements Dominions as perhaps the most compelling piece of Outsider Art in the realm of game design. By so resolutely following their own vision of what they wanted to see in a game (which was, it seemed, “everything”), Illwinter has tunneled down through the crust of good, safe game design and emerged into a molten core of pure conceptual realization. Somehow, it does that humbly.

Dominions is a game that will only be enjoyed by a fraction of people; most won’t get through the brutish, horrifically neglectful first turn screen. Even more will be bucked by the difficulty curve, or even the challenge of finding a single person to play with. But those who stick around will find something wholly unique; a game where even the developers don’t know everything there is to know. Those lucky few that survive the gauntlet will find a bottomless well in which to jump.

Dubuffet header image via Flickr.

Screenshots via Illwinter.