The Pac-Man

David Race is the best Pac-Man (1980) player in the world but would never admit that. Sure, you could watch his hand move the joystick like a professional driver downshifting around a corner. Or stand there dumbstruck as he tells you where the enemies will move seconds before they do so. “Keep your eyes on Blinky,” he’ll say. And just before you have time to ask which one that is, Pac-Man does something you never thought possible: he passes through the red ghost unscathed. Watch for a little while longer and you’ll soon realize David is not reacting to the game, the game is reacting to him. If you mention how incredible it all is, he’ll laugh and say, “yeah but it’s just Pac-Man, you know?”

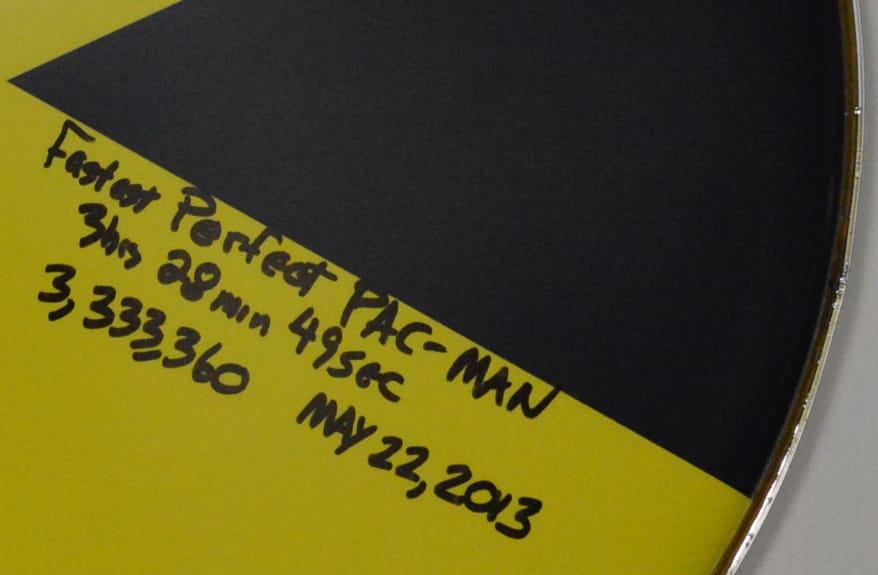

Here are the facts: to achieve a perfect Pac-Man score of 3,333,360 you need to navigate 256 boards, or levels, and eat every pellet, fruit, and ghost—all without dying. If that sounds nearly impossible, it’s because it is. Only eight people in the world have achieved a verified perfect score on a Pac-Man arcade machine. The first was Billy Mitchell in 1999 with a time of five hours and 30 minutes. Since then, a dedicated few have developed intricate patterns in order to see just how fast a perfect game could be achieved. On May 22, 2013 Race broke the world record with a time of 3:28.49. The previous time of 3:33.1 was also his. The time before that… well, you get the point.

Twin Galaxies (the authority when it comes to world record videogame scores) lists Race’s May 22nd run as the current world record—over six minutes faster than the next time. Type his name into YouTube and you can find a complete recording of his achievement. At first, it can be nerve-racking watching him play—the ghosts mere pixels away from forcing a restart. Keep watching, however, and your nervousness will dissipate. Race moves with an almost preordained precision. What’s unexpected is his reaction to breaking the record. Instead of jubilation we get indifference. “Yippee, hurray, and all that kind of stuff,” he says with mock excitement.

an almost preordained precision

This reaction got me thinking: what is it like to be the best in the world at something? What is it like to be so good, that your only real competition is yourself? What happens when playing Pac-Man transforms from hobby into self expression?

///

We first met at The Place Retro Arcade in Deer Park, Cincinnati. “How was your drive?” he asked as I stepped out of my car. At five feet nine inches, pale blue eyes, khaki shorts, and a pair of beat-up Nike Air Monarch’s on his feet, 46-year-old Race looks like the platonic form of a friendly Midwestern neighbor. “Thanks for driving all this way,” he said, and then proceeded to hold the door. We entered the arcade, and leaped back in time.

With over 60 different games from the 1980s, Michael Jackson playing over the speakers, and pinball machines galore, The Place is equal parts arcade and time capsule. Race’s pace quickens as we approach Pac-Man, and he greets the machine like an old friend. “The first time I saw one of these was in the 7th grade at a Lawson’s convenience store. It’s just one of those things, if there was a different machine then maybe I would be playing something else, but that’s something you can’t plan for.” His eyes squint and his smile widens. “I see the colors and the ghosts and I need more quarters because I keep dying. I’ve never been able to totally recreate that feeling, but it’s fun to try.”

The rules of Pac-Man are simple. Pac-Man’s goal is to eat all 244 pellets arranged in a maze while avoiding four ghosts whose goal is to eat Pac-Man. Every so often, fruit will appear that award bonus points when consumed. Located in each of the four corners of the board is an energizer. When Pac-Man eats one of these, the ghosts turn blue and the roles are reversed: for a short time, Pac-Man can now eat the ghosts for even more points.

“Pac-Man wasn’t like the other games,” Race continued. “It has these individual characters and you didn’t have to play long to learn that each ghost moved a little differently. They have eyes for crying out loud! [The game] has a simple joystick but at the same time when you first play it will kick your butt. That’s why you need to develop different strategies, different patterns.”

Patterns in competitive Pac-Man are trade secrets and for good reason—because each ghost is programmed to react based on Pac-Man’s every move, by developing a series of precise movements, expert players are able to control where the enemy is at all times. Some patterns are so precise that a half-second delay here or there will cause the synchronized dance to fall apart. If Clyde, Blinky, Pinky, and Inky are planets, then Pac-Man is the sun.

Race’s playing style is completely relaxed. Slouched to one side, legs crossed, his posture is reminiscent of someone waiting for their bus to arrive. However, his gaze is serious and grip purposeful. Using his thumb and index finger to move the joystick, his movements are so precise that if such a thing existed, he could conceivably earn a living hustling people over games of Operation (1965). Each level is designed to become increasingly more difficult, but to Race they’re all the same. He toys with the ghosts, faking one way and then going another. Each turn is taken milliseconds early like a tennis player hitting a ball on the rise. This causes Pac-Man to literally drift around corners like a souped-up tuner car. “This is called the ‘Fat-Man’ pattern,” he says as he stacks the ghosts like pancakes and eats them in a single gulp.

The pleasure in watching Race play Pac-Man comes from the realization that he has achieved an absurd level of mastery. Thought bleeds into action, and reminds you of a seasoned jazz musician to whom the instrument has become an extension of the self. This transcendent quality is difficult to articulate, but the piano player Bill Evans’ writings on art and improvisation found in the liner notes of Miles Davis’ 1959 album Kind of Blue come close:

There is a Japanese visual art in which the artist is forced to be spontaneous. He must paint on a thin stretched parchment with a special brush and black water paint in such a way that an unnatural or interrupted stroke will destroy the line or break through the parchment. Erasures or changes are impossible. These artists must practice a particular discipline, that of allowing the idea to express itself in communication with their hands in such a direct way that deliberation cannot interfere.

Comparing the way Race plays Pac-Man to the grace of a master Japanese calligrapher might seem farfetched, but is surprisingly accurate. Much like the continuous movement of a brush on delicate parchment, Race’s actions must be purposeful and immediate. In order to complete one of his intricate patterns, his character must navigate the screen’s 300 playable squares with pixel-perfect precision. The moment he thinks about what he is doing, he will die. There is no time for delay or second guessing. Instead, first thought becomes best thought. Pac-Man becomes a form of Zen—the sound of one joystick clapping.

deliberation cannot interfere

The term “best” is, of course, subjective. Some will argue that Billy Mitchell is the best Pac-Man player because he was the first to reach that elusive 3,333,360. Others might give the title to Chris Ayra who held the fastest perfect time from 2000 until 2009. There might even be votes for Canadian player Rick Fothergill who was not only the second person to achieve a perfect game (only 28 days after Mitchell), but on October 14th 2009 beat Race’s world record time by over five minutes. “I honestly think Rick Fothergill hasn’t been given the credit he deserves,” Race told me over the phone. “He’s the person who has given me the most competition. We both know how hard it is and honestly I don’t want to try for the record again unless someone comes along and beats my time. Competition is fun, but not when you’re competing against yourself.”

///

Race grew up in a small suburb in Dayton, Ohio called Old North. His mother Catherine worked at a children’s medical center, and his father David worked at a few gas stations in the area. David loved pinball and would often take Race and his two sisters to a nearby Malibu Grand Prix arcade. The six-year stretch between the years 1979 to 1984 are considered by many as the “Golden Age” of arcade games. For a time, companies like Atari, Nintendo, and Namco simply could not miss. For a time, legends were born: Space Invaders (1978), Asteroids (1979), Donkey Kong (1981), Dig Dug (1982), Tron (1982)—games so loved that they have become canon. Still, among the gods there must be a Zeus, and for many, that was Pac-Man.

It’s difficult to overstate just how different Pac-Man was compared to the other games of its time. Instead of making another spaceship-type shooting game, Pac-Man’s creator Toru Iwatani wanted a game that did not focus on killing, but instead on eating. Legend goes that, one night, Iwatani went out for pizza with some of his friends, and as he grabbed the first slice, inspiration struck. The missing slice formed a mouth and thus Pac-Man (known originally as Puck-Man) was born. Pac-Man would go on to become the first videogame mascot, the first game that had mass appeal towards both boys and girls, and would eventually go on to become the best selling arcade game of all time.

Tim Balderramos (the 4th person in the world to achieve a perfect Pac-Man score) met Race at a tournament in 2010 that coincided with the game’s 30th anniversary. He remembers the “Golden Age” as an era when the top arcade players were treated like celebrities. “In some cases players who were considered the best of the best would come in with a group of fans.” As Balderramos explains, during the early 80s, arcade games weren’t just something you did while waiting for your movie to start—high scores were taken seriously. “You had people jostling and playing mind games with you and looking over your shoulder. I had kids that would come and as I started getting better trying to study what I was doing—and there was a bit of Paranoia there. What I did was actually bury my strategy and switch techniques.”

Race, on the other hand, never reached that level of competitiveness in the 80s. While he loved Pac-Man and recycled aluminum cans to play when he could, he never dedicated the amount of time players like Mitchell and Balderramos did. He had no desire for world record scores, nor for the fame that came with them. Instead, he was just a kid like countless others who grew up playing arcade games. A kid who eventually joined the Marine Corps as a field radio operator. A kid who married and had two kids of his own. A kid who had a divorce. A kid who began playing Pac-Man to cheer himself up. A kid who found purpose in Christianity. A kid who got really good at Pac-Man. A kid who moved back to Dayton and works at the post office. A kid who became even better at Pac-Man. A kid who met a woman named Lori who would later became his fiancée. A kid who loves to karaoke on the weekends and sings a mean Bon Jovi. A kid who became the best.

After watching Race play for a few hours, we drove to a nearby Frisch’s Big Boy for dinner. Dr. Pepper in hand, I asked Race if he thought someone like me could break his record if I wanted it bad enough. He smiled, clearly unafraid of someone who has never passed the third board. “If you really want to do something, whatever you do, don’t give up on it. Things are gonna beat you down a lot more than you’ll ever find in a videogame. Some things might get you down, but you just got to push through, you know?”

“I think he plays Pac-Man because it makes him feel young again.”

We returned to the arcade and I met Race’s fiancée Lori Brunsky. “Whenever we go out somewhere, I like to tell people about David’s record because he won’t do it on his own—he’s just not that kind of person” Brunsky said. “Did you know he has his own trading card?” We talked some more: About how Race insisted he would pay for my dinner and his love of Dr. Pepper. About his sense of humor and how much he genuinely likes helping people. How next month he plans to hold a Pac-Man charity event to fight cancer. Then she stopped—her voice measured and direct.

“I want people to know he’s not one of these mom’s basement types. I think he plays Pac-Man because it makes him feel young again.”

And with that she thanked me for my time, and the two of us walked over to Race, who by now had a few people gathered around him. He tells me the best thing about having the world record is that he doesn’t need to worry about it anymore—doesn’t need to worry about scores or times. He has nothing left to prove.

“Everyone has their game,” he says aloud, eyes focused on the screen. “They just need to find it.” After a while, those playing at the surrounding arcade machines stop what they’re doing and join Race’s collective orbit. He does not notice. He is somewhere else, and he’s having fun.

///

Photos of David Race playing a Ms. Pac-Man cabinet with a Pac-Man board installed inside of it, taken by Theresa Cottom.