The tragic tale of rugby as a sports game

This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel.

After the 34-17 loss at the Rugby World Cup semi-finals last October, Australian fans could do with some escapism. But if they’re looking to relieve their broken hearts and reclaim the cup through a videogame fantasy, they’ll find that the medium is still working to catch up to the excitement of real life matches.

While annual soccer video games like FIFA plow ahead with authentic ball physics and a realistic facial rendering of Lionel Messi, rugby videogames are admirable mostly for their refusal to quit. Judging from the opinions of players, developers, and critics alike, there is a gulf about the size of the Mariana Trench between the best new soccer games and the latest rugby offerings.

Rugby fans are not alone in their frustration of putting up with bad videogame versions of a good sport. In the sales forecast-driven industry of games there are two kinds of sports games: those written with a capital “S,” and everything else. As far as mainstream videogames are concerned, the sports that matter are the ones that are most popular in countries where people have the largest amounts of disposable income to spend on them: American football, baseball, basketball, and soccer. The rest fall into a class categorized as “other.”

“Other” sports, as the name suggests, is a catchall for sports that don’t draw major attention from game audiences, and they include everything from dirt bike and horse racing, to foosball and cricket. It’s important to note that being “other” doesn’t necessarily reflect on the popularity of a sport. Cricket’s estimated 2.5 billion fanbase, for instance, completely dwarfs that of American football, but because the game is popular in places where few people buy $60 games, such as India and Pakistan, it gets placed in the “other” camp.

For a professional sport to be deigned “other” by the videogame industry usually means that all major publishers with the coin to create a top notch game have passed, leaving smaller studios to fight over the table scraps. According to Jeremy Wellard, the founder of HB Studios, one such mid-tier sports game studio, “there has never been a bigger disparity between the grade one sports and the grade two sports, and the latter is where rugby and cricket sadly reside.”

This is a cause for concern whether you care about rugby and cricket or not

This is a cause for concern whether you care about rugby and cricket or not. Some speculate that hockey is in danger of being exiled to the bottom shelf. Golf is trending in that direction. And tennis simulations have been collecting dust since the early 2010s, save for a PlayStation Vita port of Virtua Tennis 4. Sports fans could be headed towards a starkly contrasted future where a few bright and beautiful games outshine the rickety heap of outdated, subpar ones they stand on top of.

Rugby has already found itself trampled by the cleats of premiere sports games. “It is sad to say it, but it is extremely unlikely that there will ever be a day that rugby or cricket video games match FIFA, Madden, NBA 2K or The Show for technological advancement, sophistication, game mode depth or online play,” Wellard says. While the developers of these franchises have been steadfastly improving their product every season, in Madden’s case for 27 consecutive years, rugby games are released sporadically by smaller, competing software houses, and the result is a discrepancy that smacks you in the face.

This was not always the case. There was a time when there was an optimism for rugby. “We did rugby union. We did rugby league. We did Australian rules,” says Nigel Sandiford, the former president of the Asia-Pacific arm of Electronic Arts. For a run of years roughly between the 2003 and the 2008 World Cups, rugby was in the big leagues, so to speak.

These were the glory days, as Wellard tells it. He and his studio had eked out a tentative alliance where they made the games and Electronic Arts, the world’s largest publisher of sports games, sold them. The relationship had some huge advantages. Namely, they got to build rugby games using expensive technology that was developed by Electronic Arts’ crack team of engineers. Beyond that, the publisher’s involvement meant that a layer of spit-shine was evenly applied to every facet of digital rugby, from realistically rendered stadiums, to character models that were cribbed from FIFA, to motion-captured animations of the players. Even the commentary for once was decent. “That is as close to [the upper echelon of games] as Rugby ever came,” he says.

This is not an “EA is the Death Star of gaming” article. They pulled out because the Venn diagram circle that contained fans of rugby and the other one that contained fans of videogames did not overlap in a way that justified continued support. There were constant frustrations with mothering these games. Among them, the rugby league’s demanded licensing fees that were equivalent to American sport leagues like the NFL and NBA—though the vast majority of rugby games were sold in territories like Australia where the audience was far smaller and less likely to pay.

There could be a resurgence of alternative sports games

“You’ve got no idea how sophisticated the pirates are in the rest of the world,” Sandiford says. “In five days, the pirated copy is out for five bucks. What chance do you stand?”

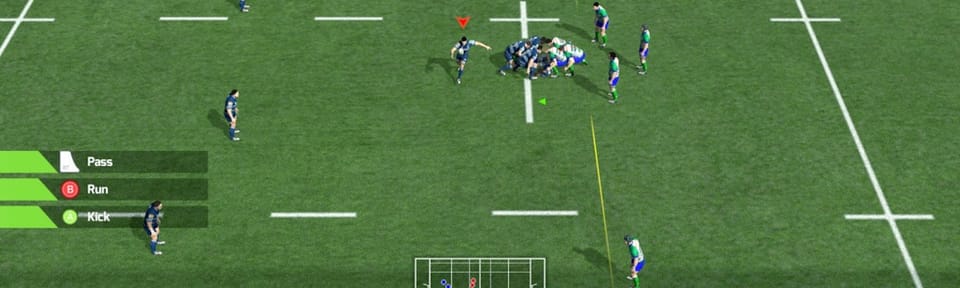

In their wake, rugby videogames have struggled for competence, but often underachieved. HB Studios’ latest rugby offering, Rugby 15, for instance, garnered an aggregate score of 19 out of 100 on Metacritic—which is considered egregiously bad. But Sandiford expressed a bit of hope that rugby games will return to former glory and compete with the privileged sports games. If games eventually make the transition from expensive consoles to ubiquitous mobile phones, as many predict they will, Sandiford says, things could change. There could be a resurgence of alternative sports games, since people in parts of the world that don’t play games on consoles would have access to them.

If not, “we had our day in the sunshine in a pretty spectacular way,” he says.