The Wargamer and I

“All play has its rules.”

—Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture (1950)

The first time I encounter the Wargamer, he is militantly editing a Word document and downing an Americano. Hundreds of red marks, crisscrosses, and deleted commas fill his MacBook screen. I make a small quip about how his desktop looks like a battlefield, and the Wargamer hastily explains that the color isn’t his fault, but rather, a courtesy of Microsoft Office. He tells me that he edits game rulebooks professionally, that he’s worked on games about pirates, migraines, and cats. I begin to laugh. I’m deathly allergic to cats, and the idea of someone voluntarily deciding to play an entire game about my nemesis, my furry feline foe, cracks me up.

Let me put my cards on the table. Games aren’t complete gobbledygook to me. As a child I was fed a heavy diet of Cribbage and No Limit Texas Hold’em poker by my parents—two pacifists, who were against military engagement in the Middle East. The only battles my dad fought were at the poker table. Though he taught me at age six how to bet and bluff, board games were never his bailiwick—or mine, until the Wargamer came on the scene.

I have no clue how to prepare for this date or for this wargame

The Wargamer is strategic, smooth, and before too many moons have passed, I start to fall for him. The fall is sudden, steep, and yet, nonviolent. The Wargamer walks to the beat of his own drummer, but he’s never on a warpath. He meditates, retweets @bunnybuddhism, reads Oliver Sacks, and has a sticker that says “Gaming’s Feminist Illuminati” on the back of his MacBook Air. I fall for the Wargamer, because he sculpts sentences and tries to bring order to the words people toss together. You see—I am one of those people, who tosses words together: I write.

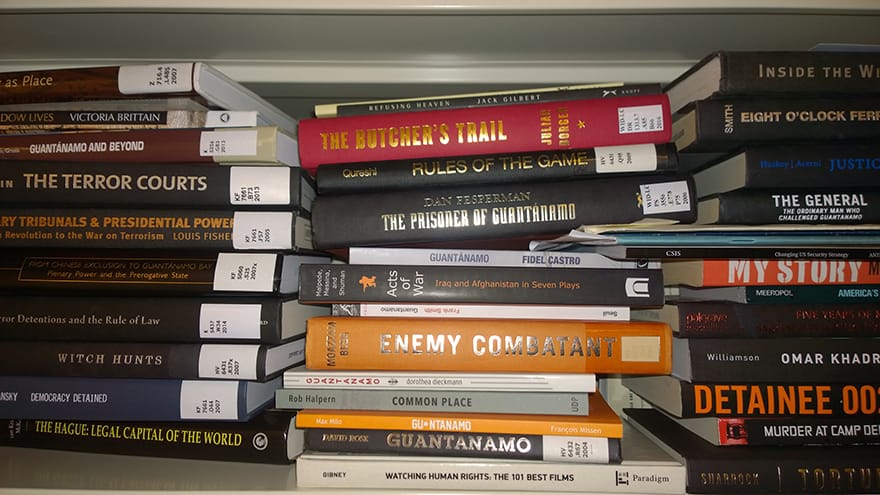

When I meet the Wargamer, I am in the throes of researching my Master’s thesis on the Guantánamo Bay Detainee Library. Emails to and from the Department of Defense clog my inbox. My bookshelf is no merry-go-round; Michael Ratner’s The Trial of Donald Rumsfeld (2008), Neil Krishan Aggarwal’s Mental Health in the War on Terror (2015), Dr. Robert H. Wagstaff’s Terror Detentions and the Rule of Law (2013), Joseph Hickman’s Murder at Camp Delta (2015), and A. Naomi Paik’s Rightlessness are strewn across my bed. Weekend fun for me is digging into the Department of Defense’s 1204-page-long Law of War Manual.

The Camp Delta Standard Operating Procedures by the Joint Task Force-Guantánamo (2004)

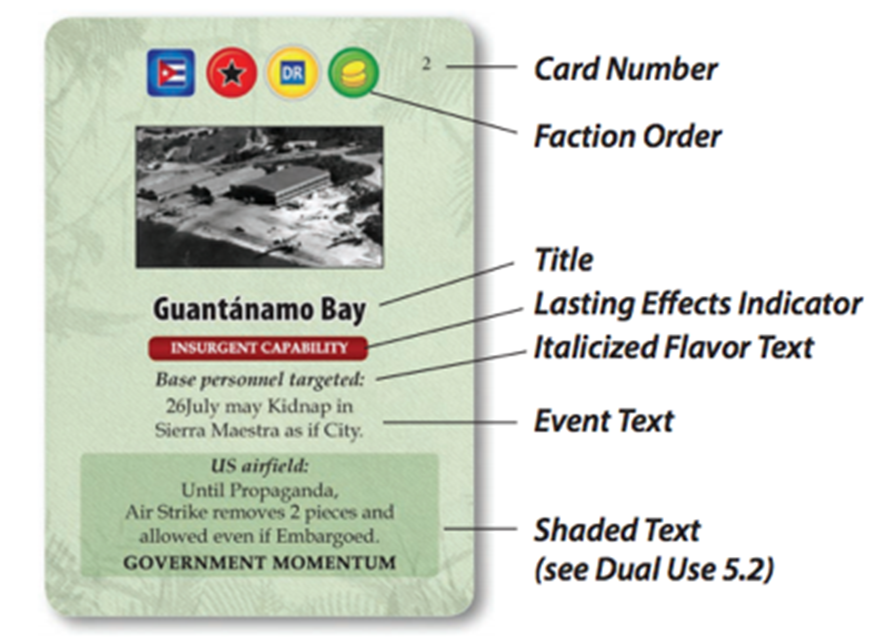

The Wargamer woos me. He invites me to play Cuba Libre! (2013). It’s a board game co-designed by the former CIA analyst Volko Ruhkne to show the complexity of Fidel Castro’s insurgency. By this time, I’ve told him I research GiTMO, and I take the plunge. I say confidently, “I’m game for your game.”

I can’t help but chuckle. I chuckle, as I try to make sense of the game’s 36-page-long manual. I chuckle, because I’m about to re-enact the Cuban Revolution in what can only be described as a Bernie bubble, a stone’s throw away from Smith College, in Gloria Steinem’s old stomping grounds, where the town’s motto is “caritas, educatio, justitia” (that’s “caring, education, justice” for all you kids who never studied Latin). I chuckle, because I’m going on a date with a dear dimpled boy, who gets his kicks out of reading wargame rulebooks. I chuckle, because after studying Guantánamo for so many months, I still embarrassingly know so little about Cuban politics, jurisprudence, and history. Let’s just say Castro wasn’t on my high school curriculum in South Carolina.

The Wargamer walks to the beat of his own drummer, but he’s never on a warpath

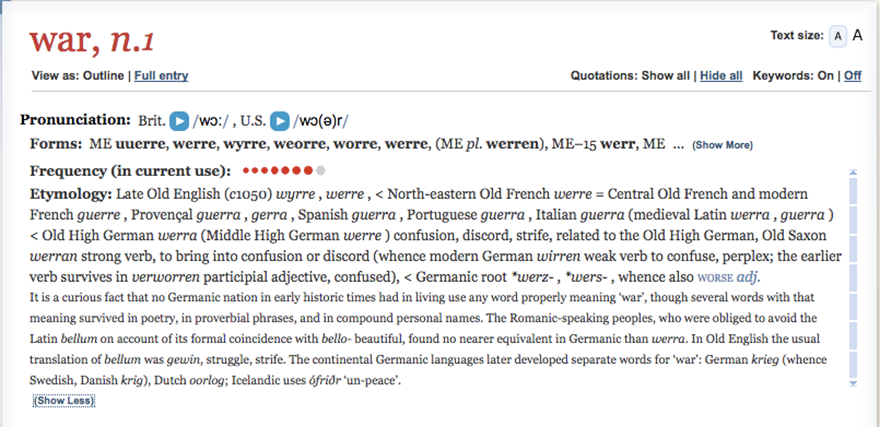

I have no clue how to prepare for this date or for this wargame. I think back to the words of Mary L. Dudziak in War Time (2012), and her declaration that “wartime is assumed to be temporary, but now we find ourselves in an era when American political leaders announce an end to hostilities—“mission accomplished”—but war continues.” A student of languages, I know how to say “war” in Turkish, Arabic, French, and even Pashto, but I realize that I’m not sure what it means. I head to the Oxford English Dictionary for some etymological counsel, but it doesn’t help me much.

Definition of “war” according to the online edition of the Oxford English Dictionary

I turn next to the Late Night Gamer, a YouTube channel run by a Norwegian guy, for some preliminary advice. I click the link and an ominous voice tells me, “Night has come. The family’s gone to bed, so the Night Gamer strikes again.” And it’s when I see the board on the YouTube video that I lose it entirely. I can’t stop laughing. There are red, yellow, green, and blue cylinders; Propaganda and Event cards; discs; die; and of course, factions. This is war. I close my laptop, take out some sourdough starter, and as I knead the dough, I prepare for battle.

The Playbook for Cuba Libre! (2013) by Jeff Grossman and Volko Ruhnke

I make my way to the Wargamer’s home with a cardamom-and jalapeño-infused sourdough loaf in hand. There, waiting for me are three other players, three guys hailing from varying corners of North America. This demographic doesn’t come as too much of a surprise. (On the blog PAXsims, Rex Bryne eloquently reflects on this issue of gender imbalance in the wargaming hobby world.) But no matter—what counts—is that the Wargamer is also the Resident Rule Explainer. He’s focused and clearly on a mission, but there’s no way this dear dimpled twentysomething wants to intimidate or alienate. So even though, at first, I have no idea what I’m doing, and I’m scribbling down words like “victory condition,” “victory track,” “momentum,” and “attack operations” on a piece of college-ruled paper, I’m adrenalized. There’s even a card about Guantánamo Bay.

A playing card from GMT Games’s Cuba Libre! Excerpt taken from the Rules of Play (2013)

Having been raised by a veteran of Manhattan poker clubs, I decide to play the Syndicate (a.k.a. the Mob) and fight to expand “my” casino empire.

Months after playing, I still don’t remember how many casinos I opened or how many cash markers I placed under guerilla markers. I don’t even know who got to play the Guantánamo card. But, as I walk home that November night, I begin to grapple with this idea that a board game can model the strategic quagmires facing different stakeholders in a system. Fulgencio Batista’s Cuban government doesn’t want what the 26 July Guerillas want. The Directorio Revolucionario doesn’t want what the Syndicate wants. All four duke it out on the board. To win a player has to take the motivations and goals of the other factions into account. Ultimately no one wants the same thing. To put it in ludolingo: each faction has a different victory condition.

I pause to think of what Guantánamo might look like as wargame. I briefly escape my books. I take a break from interviews and emails. I think of the journalists trying to track down information, of the habeas corpus lawyers in the military tribunals seeking justice, of the detainees fighting for freedom, and of the guards striving to maintain order. They’re all part of a system that I am trying to decipher from afar.

It is too tempting to gamify the relationship

Under the night sky of Northampton, Massachusetts, the Wargamer gives me a crash course in game mechanics and confesses that his first attempt at designing a game bombed. He tells me that after reading Greg Mortenson’s Three Cups of Tea (2006), he once tried to make a two-player game about porters and Sherpas in Nepal. I fall a bit harder for the Wargamer. I find beauty in the way the Wargamer deciphers each and every rulebook. I see symmetry in what we do: I examine policies and procedures at GiTMO, while he tweaks the structure of fantasy worlds, one rulebook at a time.

The Wargamer and I gradually work our way through a number of the games designed (or co-designed) by Volko Ruhnke, including Labyrinth: The War on Terror, 2001 – ? (2010) and A Distant Plain (2013). The Middle East, the Soviet Union, Afghanistan—I had no idea that there was a sub-genre of board games devoted to modelling conflict in these regions. We debate and debrief game design. The Wargamer plays A Distant Plain (2013) with me and asks his friends, “Would you play a game in which one playable side was the Taliban? Would you ever play as the Taliban if it helped you understand them?”

I have questions of my own. How would we experience Cuba Libre! (2013) differently if we played it with Cuban ex-pats? What would Afghan politicians have to say about the design of A Distant Plain? What strategies could game designers use to introduce more women into the world of wargames? Someday will I be able to design a wargame of my own? Occasionally we get ambitious and tweet questions directly to the Master Wargamer Volko Ruhnke himself.

Labyrinth (2010) is the first wargame that I win outright, and it is also the last time I play with the Wargamer.

We begin one day in May as two wonkish wargamers, and end it, strangers on the street.

I have other battles to fight. Those are his last words. I am swiftly expelled from—what I’ve come to nickname—his Ludoland. It is too tempting to gamify the relationship, to think of the different cards that could have been played. I reflect on the fact that as I delved deeper and deeper into the Wargamer’s world, I forgot to give him a full tour of mine. The thesis chapters not shared, the conversations about Guantánamo not had, they all stack up in my mind like soldiers preparing to go to war. But I am no general.I flee.

Photo of the author’s bookshelf (2016)

I cram my books in a beige roller bag and hop on a bus from the Bernie bubble to Boston.

My research on GiTMO expands in ways I could not have predicted. I dive into the corpus of GiTMO literature. I get into a tangle with the Department of Defense Public Help Web Desk about a series of broken hyperlinks in an important report that was prepared for President Obama back in 2009. I begin a correspondence with a convicted war criminal at the International Criminal Tribunal of the Former Yugoslavia. I have lunch with a law professor, and together we ponder how GiTMO will be taught 50 years from now. I even try a Meal, Ready-to-Eat (MRE), a food ration used by the U.S. military.

It’s a feeble attempt at self-exile.

Wargames follow me.

One day I find myself almost by accident in a bunker-like room with someone, who wants to make a game about the Nuremberg Trials. I later email a coworker at the Harvard Law School a link to a video review by Shut Up and Sit Down of the Virgin Queen (2012), one of the more complicated wargames produced by the popular publisher GMT Games. There’s this great line at the end, where one of the reviewers says, “Let this be a warning to you. If you want to experiment with wargames, just do your homework first.” It gets me everytime. The next week I casually mention my love for another GMT wargame, A Distant Plain (2013), to my new roomies—a rock star all-female team—and they demand that we play. As I start to set up the board, ready to explain the rules myself for the first time, I can’t help but crack a smile.