The year in boardgames

“2015 is the year of the board game,” I told everyone I knew. I wrote it out in emails. I typed the words out in text messages. I casually said it over the phone. If friends or family wanted to get me something for my birthday, a PlayStation gift card would not do: I had a manicured Amazon wish list pruned with all the games I wanted to play. Sure, I occasionally played games on a screen. But people know, now: when they invite me over for dinner, they better be ready to play Love Letter or Netrunner or whatever I’ve managed to stuff into my backpack.

I’ve seen others go analog, too. Our gaming PCs and high-fidelity graphics cards may be able to render each follicle on every neo-futurist assassin’s soul patch, but they’ve got nothing on the experience of tabletop gaming. The finest AI can’t manufacture the electric betrayal in a late-evening game of Coup, or the cold social gerrymandering in the Game of Thrones board game. In that way, tabletop gaming is to videogaming what theater is to cinema production: it’s smaller, more intimate, fueled more by social rapport than production.

There’s a renaissance of cardstock and meeples in the works. Analog is in. Even if a solar flare fries every smartphone and CPU and society reverts to the Stone Age, there will still be boardgames. Below are some of the best examples of analog gaming to come out in 2015.

Pandemic Legacy (Season 1)

A surprisingly emotionally charged year-long plague simulator.

This is probably the most exciting (and hyped) release all year, because every piece of the game crafts a distinct, urgent experience. The original Pandemic was a tense, timed puzzle that wrapped up in around an hour. Pandemic Legacy doesn’t reset when the group finishes for an evening. The Legacy format prompts its players to tear up cards, unbox secret compartments and mark up the game board as the virus mutates and cities crumble under duress. At the end of a full playthrough, a copy of Pandemic Legacy will be unusable, scarred with memories, and utterly unique.

This iteration of Pandemic is as tightly wound as its forebear, but Legacy is specifically built to produce a serial narrative. The characters are archetypal—Medic, Researcher, Scientist, etc.—but each player gives their character a unique name. When shit goes down, they receive ever-more punishing psychological scars; they bring in their siblings and friends to help; they die tragically or disappear into wreckage. As characters succumb, the players have to withstand escalating punishment as the strains of pathogen mutate and the objectives evolve. The group might think they’ve cured the black virus only to see it grow more vicious and impossible to treat. It’s like a less self-aware tabletop relative of the Russian plague simulator Pathologic.

Pandemic Legacy embraces the tactile presence of tabletop gaming, which is likely what has made it so beloved. There’s something weighty about dismantling the game engine or permanently opening dossiers as a reward. The game itself is designed to become a relic: it documents the group’s narrowest victories and breaks down in response to their failures.

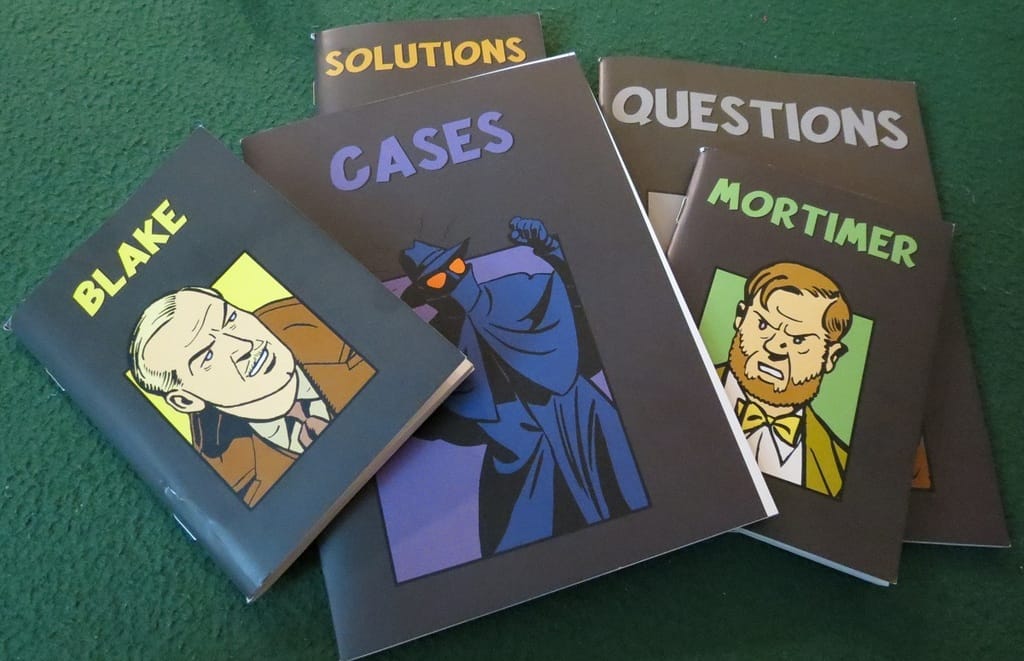

Witness

Belgian subterfuge Telephone.

Four players seat themselves in a specific arrangement, according to their characters. The profile pictures are brightly colored, hearkening back to the glory days of the old Belgian Tintin magazine. One player reads the details of a case out loud: a jewel theft, a rogue spy, a grisly murder. The players pick up their casebooks, furrow their heads in frustration, commit the details to memory. After a moment, everyone puts down their casebook, and two players whisper from memory everything they read to the other two. A pause, then another round of whispering between other players, and another, then another. The details travel around the table. At the end, the players furiously scribble everything they learned on a scrap of paper, and one player reads out a series of questions for everyone to answer. The winner is the player who got the least wrong.

Witness is brief and full of embarrassment. A game of Witness is more or less twenty minutes of cramming for an exam via Telephone: players with the best short-term memory will shine. Those with poor retention will be scorned. It’s obvious when someone has forgotten his clue. Yet even with a few missteps, the structure of each round means that the players can often piece together enough clues to form a coherent theory. Rounds are short enough that, even when a group is hopelessly lost, they can easily finish and move on to a fresh challenge.

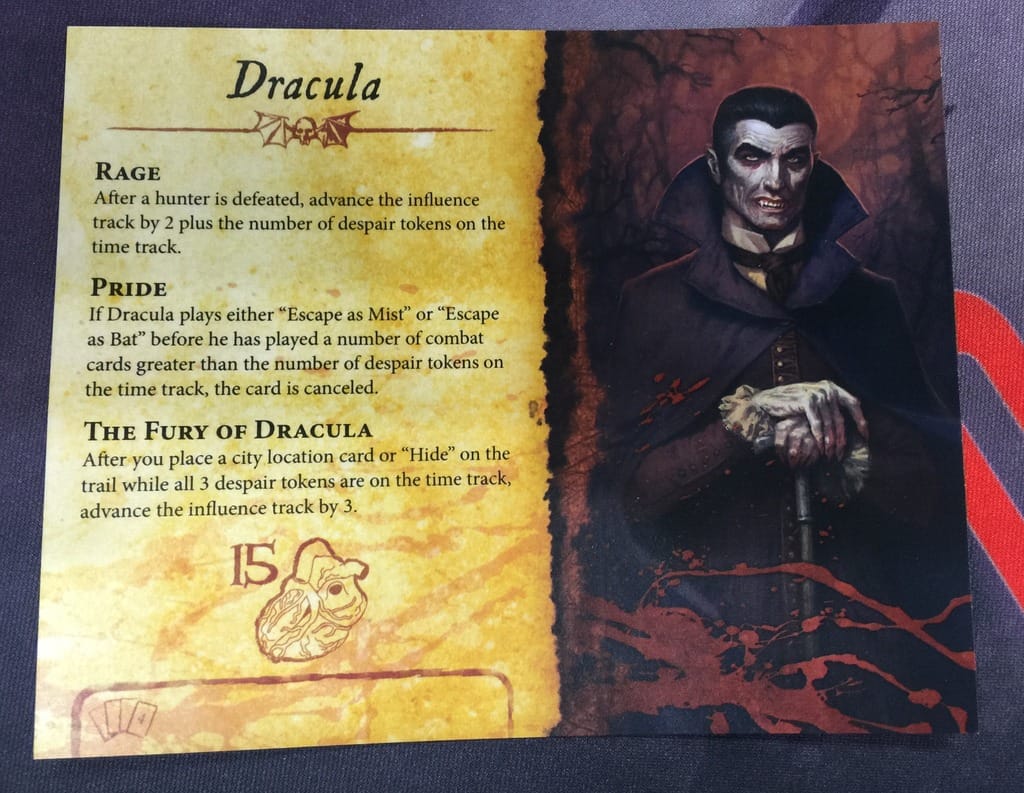

Fury of Dracula, 3rd ed.

Vampire hunting, alone or with friends.

Fury of Dracula is a game about the chase. One player, controlling Dracula and his minions, threads a careful path across Europe, leaving fresh vampires, dusky tombs, and strange weather in his wake. As hunters, several other players spread a wide net. They buy garlic wreathes and train tickets as they try to find some trace of the Count’s trail. The game ends either when Dracula has garnered enough influence to rule the people of Europe (or at least keep everyone from leaving their homes after dark) or the hunters have killed him.

The game is actually quite old, printed in 1987 by Games Workshop, but the third edition, released this year, represents a trend toward building games in which mechanic is wholly subservient to theme. Travel has been simplified, timers sanded off, dice eliminated. Combat in Fury of Dracula is tense, lasting no longer than six rounds, and serves to underscore Dracula’s intimidating power, as well as the fragility of the hunters. There are no numbers here: only tense, nail-biting worry. And wooden stakes.

Fury of Dracula is best played in character. The game is mechanically engineered to encourage players to despise Dracula for his perfidy; as such, it helps to play Dracula with a hint of arrogance. In one game, as the Count, I confronted Mina Harker and a now-ancient Van Helsing several leagues from Castle Dracula on the eve of my victory. I was drunk with power. A well-placed stake, some garlic, a holy incantation, were just enough to put Old Vlad down for good. Everyone breathed a sigh of relief: the hunt was over. As in Bloodborne: the intensity and release hurt so good we didn’t even care who’d won.

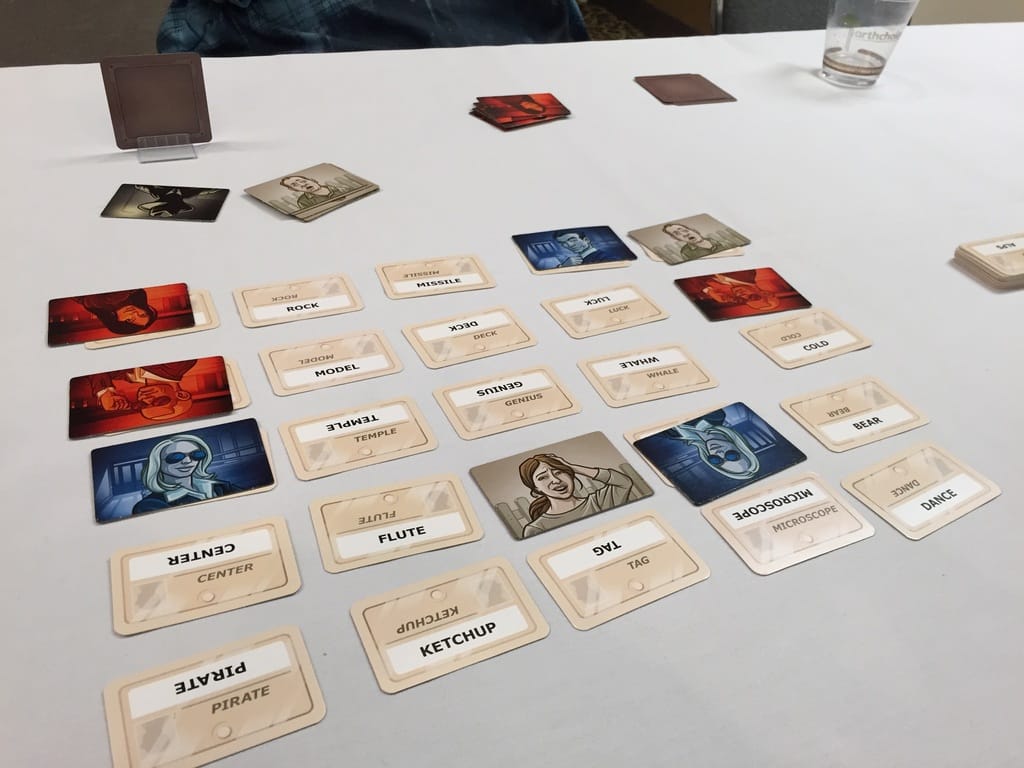

Codenames

A psychological word game.

Two code masters, referencing a shared private grid, point their team to a network of informants via simple verbal clues. Imprecise wording could mean hitting a civilian, tapping an assassin (resulting in an instant game over), or giving the other team points. A well-thought clue could mean an easy win. It’s deceptively simple.

Codenames is a new gateway drug for boardgaming. The explanation and setup are easy enough to lure an uncle or grandma to the kitchen table, and it’s simultaneously cooperative (agent and codemaster) as well as competitive (red and blue). If a master is trying to push agents to “bond” and “tick,” she might say “gadget 2” which inadvertently could point agents to “apple.” Agents might completely miss certain hints: knowing the cultural and psychological subtext of a single word is vital to success.

Like Chess, Stratego, Poker, or a bunch of other games I’ve never had the patience to play more than a few times, Codenames rewards mental acuity as well as aplomb; it is accessible enough for people who don’t frequently play games and complex enough to invite mastery. What sets it apart is its social and psychological dimensions. Depending on the group, the same clue might carry a completely separate meaning in one session to the next, and the box is stuffed with so many cards that there’s little risk of the game getting stale with use. Creator Vlaada Chvatil is known for honing intricate systems, but Codenames might be his most compulsively playable game to date.

Mysterium

If Clue were a séance.

In the wake of a grisly murder in Mysterium Mansion, a wave of psychics descend on the old manor to divine the details of the crime. One player, playing the ghost, must communicate a specific message (person, location, weapon) to each psychic via extremely abstract dream imagery. If each psychic can discover his/her three answers in seven rounds, the group has a chance to cull the true perpetrator, etc. from the tangle of visions.

Codenames and Mysterium are odd cousins. Where the first relies on careful, deliberate verbal cues, the latter thrives on misdirection and abstraction. In Codenames, failure is to be avoided at all costs; any failure in Mysterium becomes a kind of glorious theater that unfolds after the game as psychics can finally ask the ghost questions. “How the &$^# was a mouse riding a unicycle and raining knives supposed to point me to the hunter?”

Mysterium is also, without a doubt, the most visually stunning game on this list. Its sturdy deck of oversize cards brims with colorful dream imagery; a large illustrated clock counter tracks the hours in the game. The players’ success in the game hinges upon very subjective imagery, its aesthetic appeal, and the complicated psychology of getting into each others’ headspaces. If a psychic and ghost “get each other” outside the game, they’re more likely to intuit a vision, which is potentially as satisfying as it is personal. Or they won’t. Success is sweet. Failure is rarely as disappointing as it is hilarious.

Android Netrunner: Data & Destiny

“Game-changing” doesn’t do it justice.

Three years in, the two-player, collectible card game Netrunner is in top form. Its major recent expansion Data & Destiny deserves a place on this list not just for what it introduces into the Netrunner metagame but also for what it represents in the game’s larger development arc. Each consecutive release tips the balance of power in favor of a specific faction, a strategy: a single asset might render an old play irrelevant, or a new card might finally slot into a burgeoning archetype. A good Netrunner release will subtly but significantly shift the game in some new direction.

Data & Destiny casually upends everything. Beyond providing a slew of muscular new cards for the last of the game’s factions—the data-driven marketing network NBN—the box contains three new micro-factions for the hacker “runners.” The new factions aren’t simply subtle parodies of their runner counterparts: they are reinventions. For the punk Anarchs: an insatiable computer virus who destroys the board. For the artistic Shapers: a Frankenstein’s monster who hacks servers as a kind of performance art. And the Criminals, always in it for the $$$, have a security agent who hacks for her day job so she can feed her kids.

From a purely conceptual standpoint, Data & Destiny feels fresh, but the cards here have only just begun to be digested by the Netrunner community. The game is in process of constantly being reinvented: a card *breaks* the game, and a new combo breaks that card, and so on and so forth. There is no shortage of imagination here.

Lead photo by Paulo Renato on BoardGameGeek.

Pandemic Legacy photo by yoppy on Flickr.

Witness photo by Daniel Thurot on BoardGameGeek.

Fury of Dracula photo by Cody Jones on BoardGameGeek.

Codenames photo by Wayne McIlvaine on BoardGameGeek.

Mysterium photo by lelo arrowsmith on BoardGameGeek.