The Year in Feels

If we had access to some grand compendium filled with every single emotion that videogames make us feel, it would probably waste most of its words trying to describe fun. But as a concept, fun is primitive. Fun is escape. Like a dog chasing a tennis ball or a crow sliding down a tin roof, fun is intuitive. Fun is smashing your thumb down on the square button while Kratos slings around his orange blades. Fun is nailing that QTE and watching Kratos pull out the cyclops’ eye. Fun is when the red blobs come out and makes Kratos stronger, so that next time you push square his chainblades sling longer and harder. Fun is release.

But fun can also get stale very quickly. Even though videogames have already begun to reach beyond the concept of “fun” to carve out their own emotional lexicon, they’ve never broken quite as much new ground as they did this year. From smoldering teenage infatuation to hopeless desperation and real-life tears of joy, 2015 felt like the year that people up and went for it, unleashing their deepest emotions without so much as a hint of reservation.

///

It starts with denial. Three dudes in button-up shirts and one bewildered-looking woman sit in a semicircle, listening intently as an industry executive slowly lifts the veil on a new project. When familiar images of a blond spiky-haired man and his big burly sidekick start to pop up on the screen, the men clutch at their hairlines in agonized disbelief. One of them climbs onto his chair. Another starts to mutter under his breath: “No. No. No!” The word R E M A K E spreads across the display, and nobody even has to tell them it’s a Final Fantasy 7 remaster: they know. The ensuing freakout is familiar to anyone who’s doggedly followed a cherished videogame series, but there’s an almost sobering voyeurism to this video, like peering in at these guys in a moment of private ecstasy.

With platforms like Twitch and YouTube Gaming still gaining meteoric traction, esports is more popular than ever, and players are in closer proximity than they’ve ever been. But the extent of that human interaction has jumped way beyond fleeting teamwork and Pokemon crowd-play. At the League of Legends World Championship, Marcus “Dyrus” Hill—the Tim Duncan of LoL—announced his decision to retire from the game with a fumbling tearjerker of a farewell speech that had even the interviewer struggling to find words. It’s the kind of moment that translates beyond esports and even beyond games; Kevin Garnett’s “anything is possible” celebration and Kevin Durant’s moving MVP acceptance speech come to mind.

It starts with denial.

It’s a strange instinct to wonder whether games can make us cry. Not only is it an awkward system of emotional currency that equates tears with sentimental aptitude, but it fails to acknowledge how those emotions are created. Even though esports have only been mainstream for a few years, they’ve built their massive followings on the diligence and fervor of their player bases. It’s not an orthodox angle, but it denotes a major fork in the path between games as systems for emotional investment, and games as self-contained emotional experiences.

///

For most videogames, emotion has always been more of an afterthought than a prime virtue. In a majority of cases, gravitas feels either out of place (Gears of War), contrived (To the Moon), or directly at odds with what’s happening elsewhere in the game. This year’s Rise of the Tomb Raider, like its 2013 predecessor, pushed a bittersweet “honoring father’s legacy” premise that felt completely detached from its ultraviolence.

Feelings worked best this year under the delicate care of the “walking simulator,” a genre known for prioritizing dramatic, aesthetic, and artistic appeal over fun. It doesn’t jive too well with the base utilitarian Fun Value we tend to break games down into, but the ability to hone in on story beats and thematic elements without drawn-out grinding or combat gives them a sense of focus that’s completely absent from your average 50-hour RPG.

That being said, these games haven’t done much to flip the anti-fun stereotype. The walking sim poster child Dear Esther, from UK-based studio The Chinese Room, was essentially a long hallway with tripwires that’d play long monologues after being triggered. Paired with the solemn, elegiac voiceover work, it was hardly a populist triumph.

The Chinese Room’s 2015 effort Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture, by contrast, had an almost Spielbergian everyman appeal, tapping both the pastoral beauty of the English countryside and the solitude of the post-apocalypse in equal measure. Rapture’s method of filling that empty void was almost sublime in its warm serenity; vistas of rolling meadows and firefly manifestations of human spirits instantly related the game’s poignant themes of loss, sacrifice, and love. Paired with the approachability of Dan Pinchbeck’s script and gorgeous orchestral arrangements from Jessica Curry, there’s a grandiose, cinematic sense of production to the entire work. Each vignette takes on its own life within the larger tapestry, deftly swelling and subsiding and building up again into eventual catharsis. It’s a dense work of moving honesty, gathering the individual talents of its creators to create one cohesive whole.

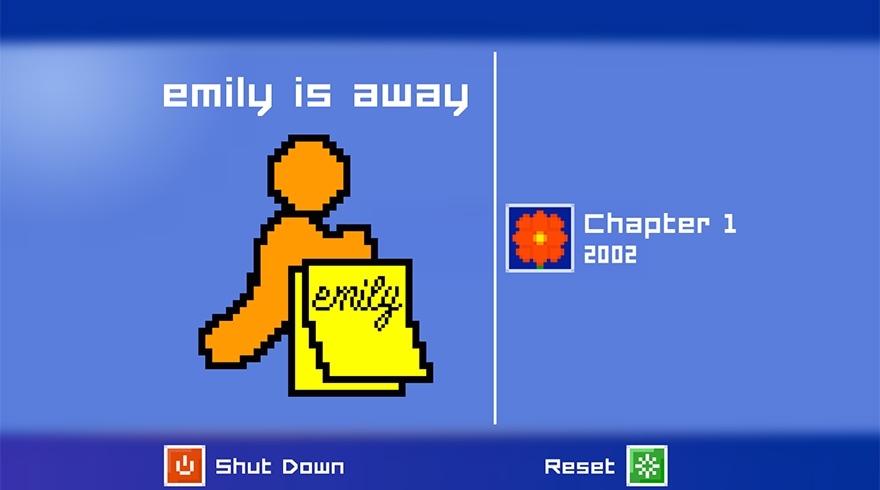

A host of smaller games leaned mostly on personal experience, creating a fleet of smaller, weirder, and completely singular works of raw, unrefined passion. Most of these games feel so deeply personal that it feels wrong not to pair them with the names of their creators. Just like Do The Right Thing seethes with a brand of impassioned frustration unique to Spike Lee, games like Nina Freeman’s Cibele, Davey Wreden’s The Beginner’s Guide, Kyle Seeley’s Emily is Away, and Matthew Burns’ and Tom Bissell’s The Writer Will Do Something all carried the emotional stakes to immediately suggest auteur status.

It’s easy to picture a lone artist creating these works in a dim room

Like Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska or Bon Iver’s For Emma, Forever Ago, it’s easy to picture a lone artist creating these works in a dim room, writing out scripts and hashing out aesthetic details while recalling some of their most traumatic or most cherished experiences.

The Twine-produced choose-your-own-adventure The Writer Will Do Something is probably the rawest of the bunch. Using onscreen text to convey the debilitating pressure of high-budget videogame writing, it feels like a PTSD flashback, with roundtable arguments escalating ad infinitum and an ending that offers no clear solutions. The fact that this game exists at all feels like an act of bravery: most people wouldn’t leave a bad comment anonymously on Glassdoor, much less attach their name to an industry exposé.

Nina Freeman’s Cibele and Kyle Seeley’s Emily is Away work well as companion pieces. Both use computer interfaces to tell their stories, and both call back to the early- to mid-2000s. But the interface-as-setting isn’t so much a generational statement as it is a way of recreating familiar digital scenery. In Emily is Away, which takes place entirely within AOL Instant Messenger, the creaking door alert sound is an instant time jump to the days of shitty MySpace HTML tweaking and awful XP-era interface design. With the game’s main conceit following two would-be lovers over a five-year period, AIM functions as a séance for modes of human interaction that have long been obsolete.

Nina Freeman’s Cibele pulls a similar trick, but injects its creator directly into the narrative. As the player navigates Nina’s desktop, they find samples of her old poetry; pictures of her with friends; selfies she’s taken in lingerie. It all feels unsettlingly private, but gives the player unprecedented access to the awkward spontaneity of her online love. The full-motion video sequences break up the interface’s carefully-crafted immersion, but it’s all on purpose: this is what a “living, breathing world” really looks like, and Cibele has the audacity to welcome it with outstretched arms.

///

The influential Russian film director and theorist Sergei Eisenstein saw cinema as a complex vehicle that worked best when “exercising emotional influence over the masses.” As a lifelong student of the form, his obsession with film’s intricate machinery culminated in some of the most influential films of the 20th century.

Although they’ve had their John Carmacks and Will Wrights and Sid Meiers, videogames haven’t quite met their Eisenstein. Then again, videogames are more systemically complex than films, and it can be hard enough to make something that’s consistently fun, much less to build something that holds any semblance of emotional influence.

this is what a “living, breathing world” really looks like

After releasing the critically acclaimed walking simulator The Stanley Parable in 2013, Davey Wreden withdrew from the public eye, struggling to pin down his place in a universe filled with the interpretations and opinions of outside observers:

Every time I turned to someone else’s opinion of the game, I felt less sure of my own opinion of it… So: to help myself better understand and isolate the feeling of depression around the GotY awards, I wrote and drew a comic to explain what I had been feeling… I just wanted to put it into some words to help make it less nebulous and unknowable.

The Beginner’s Guide, released in October of 2015, is Wreden’s second attempt to deconstruct—and then understand—the psychological inner-workings of his art. The game is a labyrinth, not just in its unsolvable puzzles and oppressive imagery, but in its complex weaving of characters and creators, players and developers, reality and fiction. To interpret The Beginner’s Guide is an impossible task; there’s nothing beginner-friendly about it. But to Wreden, a man whose prime obsession has been to make sense of his art and his status as a creator, it’s the perfect starting point.

At the end of The Beginner’s Guide, Wreden makes a desperate plea to Coda, his imaginary game-developing muse: “I know that I did an awful thing, and I’m doing it again right now: I’m showing people your work—but I can’t stop myself from doing it. That’s how badly I need to feel something again, like I’m an addict.”

Most people have their own hang-ups, whether it’s detachment or addiction or an insatiable need for self-validation. For about as long as they’ve been around, we’ve cherished videogames as a way to escape from these vices and from the many other stresses of everyday life. But games can serve the opposite purpose just as well, and the most emotionally resonant games of 2015 opted to confront us with truths instead of helping us avoid them—whether they were ugly or embarrassing or cheesy or pathetic. It might not sound like much, but it’s a solid foundation for a more personal, more incisive, more emotional videogame medium.