The year in graphic adventures

Growing up, graphic adventures were essential. Sure, I might have gone to Greg’s house to race through some Mario Kart tracks now and then, or called up Izzy if I were looking for the vicarious thrill of watching him charge the dark corridors of DOOM (I was too skittish to actually play). But at home on my dad’s IBM were the mainstays: a treasure trove of epic adventures with funny dialogue and exotic, lushly rendered locales where I could hang out and explore for hours on end. The Caribbean, the lost city of Atlantis, the increasingly satirical lands of Daventry or Kyrandia … these were my preferred virtual worlds. They didn’t threaten death at every turn (which made me anxious) or demand adroit motor skills (which I lacked). Instead, they offered the kind of interactive storytelling that seemed to me the very point of art, as I was beginning to understand the concept. You just couldn’t find this stuff anywhere else.

the kind of interactive storytelling that seemed to me the very point of art

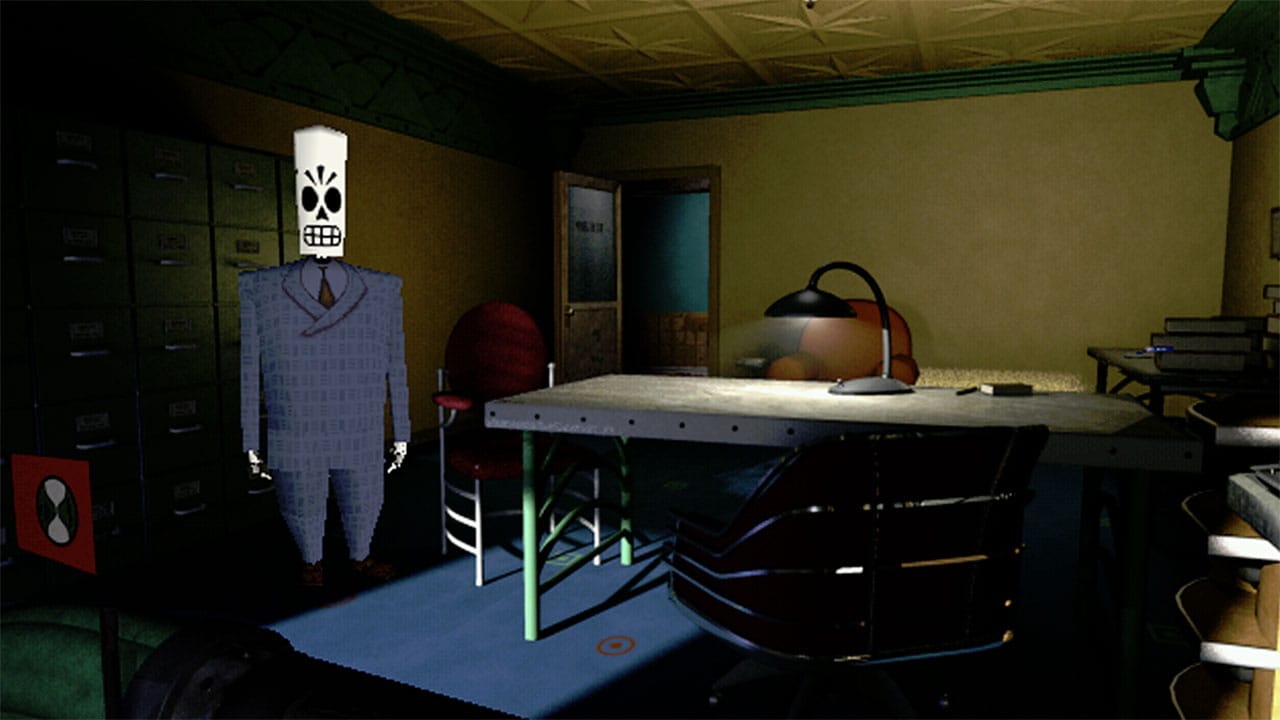

In 2015, graphic adventures aren’t so essential anymore. As I have prattled on about at length, the philosophy behind the ‘90s “golden age” of graphic adventures had a diasporic impact on the videogame industry just as the genre was entering a decline. Emerging designers inspired by classics like Grim Fandango, Gabriel Knight, and countless others would incorporate the qualities that made those games special into other genres. As a result, we now no longer rely on graphic adventures as the sole bastion of character development and narrative sensibility in videogames, which, all things considered, is a very good thing.

At the same time, this year has featured a high-profile showing of several new but traditional graphic adventures. There is a cynical way to account for this. People like me—for whom graphic adventures are inextricably tied up with nostalgia for the innocence of youth—are now old enough to put some disposable income toward crowdfunding campaigns, out of which several of 2015’s graphic adventures emerged. The upsurge in this “non-essential” genre could then simply be viewed as a retro effect: a futile attempt of an aging generation to reclaim something we lost through the mere act of growing up. And, as Proust warns, our memory of the past is not the same as the past itself; you can never really go back.

The question, once the nostalgia wears off, is this: do the games hold up? In the worst cases, playing a new graphic adventure can feel like little more than a poorly aged friend imploring you to “remember the good times.” But such entries were in the minority this year; most of 2015’s notable graphic adventures dabble in nostalgia but do not linger there, instead asserting a modern relevance that serves to justify their place on our harddrives.

///

Armikrog is the worst-case scenario: a pure bid for nostalgia which by its nature is a proposition doomed to failure. The game was created as the spiritual successor to 1996’s The Neverhood, a fondly remembered claymation graphic adventure. Armikrog banked on the notion that replicating a past success would be enough to appease a contemporary audience, but doing so only served to highlight the flaws of its dated approach, and in so doing imply flaws in its predecessor. Evoking feelings for a bygone era without offering anything new can only produce feelings of sadness and resentment. The Neverhood’s biggest selling point was its gorgeous animation, and Armikrog also looks great—but, you know, lots of games look great these days. Playing Armikrog wasn’t just frustrating for its own apparent disinterest in making something fresh; it made me wonder if in fact The Neverhood wasn’t as good as I remembered it.

How dare you promise to take me back home

Perhaps ill-advisedly, I dug up my old copy of The Neverhood and ported it into ScummVM. Sure enough: its presentation of story struck me as lazy, its puzzles abstract to the point of seeming spiteful … I’m getting upset just thinking about it. How dare you, Armikrog. How dare you promise to take me back home, where neither I nor anyone else can ever go, only to leave me with an attractive, vapid, buggy little game, not to mention a bunch of ruined memories.

///

Going into it, I expected that the episodic revival of King’s Quest would travel Armikrog’s same path, tugging at the strings of nostalgia until they break. Perhaps the foundational franchise of the graphic adventure genre, I hadn’t touched a King’s Quest game since 1990’s aggressively boring Absence Makes the Heart Go Yonder!, the fifth entry in the series. I assumed that the newest incarnation—the first episode of which is titled A Knight to Remember—would evoke a little fondness, a lot of frustration, and ultimately would do little to justify its existence.

To my surprise, A Knight to Remember is sheer delight. The story feels quintessentially modern: a nebbish but clever young knight seeks adventure in the celebrated kingdom of Daventry, only to find it mired in bureaucracy. Guards place caution-tape around dangerous areas, bridge trolls are on a labor strike, and proving oneself as a knight ends up having less to do with heroism and more with jumping through increasingly obscure governmental regulations. As a result, the genre’s classic inventory/environment-based puzzle-solving fits like a glove; lateral-thinking feels like the only way to disentangle Daventry’s profoundly unromantic officialdom. The game also lets in more contemporary influences through the use of (mercifully brief) quick-time sequences, some spatial-reasoning type puzzles, and several nods (and a few jabs) to Telltale Games’ successful “so-and-so will remember that” approach to adventuring.

The new King’s Quest ended up being, in a sense, more than I remembered. Inspired casting and a whimsical score elevate the charming, pun-filled dialogue beyond what the old VGA games could achieve. I’m an adult now; older, harder to faze. Nothing can replace the contradictory mixture of glee and horror that I felt the first time I watched Sir Graham being devoured by a moat monster in Roberta Williams’ original King’s Quest. The beauty of A Knight to Remember is that it doesn’t try to bring me back there: it is a new entry in an old series, which helps cement the idea that there really is something worthwhile about graphic adventures even after the nostalgia washes away.

///

A further step removed from the trappings of nostalgia is Double Fine’s Broken Age. In this case, the game itself did not promise a return to the past, but its meta-narrative did: as an early Kickstarter success from designer Tim Schafer—who created three of the golden age’s most beloved graphic adventures in Day of the Tentacle, Full Throttle, and Grim Fandango—Broken Age came to represent the potential resurrection of the genre, as though graphic adventures had been preserved in amber for the past two decades. If you carry the burden of this expectation as you play the game, it will disappoint—nostalgia always does, in the end. But if you are able to see Broken Age for what it is, you will find that it stands as a prime example of what new graphic adventures can offer.

as though graphic adventures had been preserved in amber

Broken Age essentially takes the hallmarks of the genre and amps them up with the technical and artistic prowess that is available in contemporary game design. The art, sound, and music are among the highest quality you will experience in any game this year, and they combine to tell a sophisticated story about the pain and excitement of growing up. Broken Age is, itself, an embodiment of that journey: the graphic adventure growing up. It may not be all the way there, and certainly it’s not without some bumps along the way—I don’t know that the traditional puzzle-solving fits as logically here as in a game like King’s Quest, though Broken Age’s commitment to that approach does compel the player to engage in a slow, relaxed manner, which is essential to the game’s dreamy atmosphere and parable-esque storytelling. Regardless of its growing pains, Broken Age emerges as something familiar but still vital, something in process, capable of holding onto the old without being bound by it.

///

Lastly we come to a game that neither in itself or its creators has any direct connection to the golden age: Stasis is simply a new graphic adventure. To be fair, there is a nostalgic pull: its isometric perspective and horror theme recall 1998’s Sanitarium, a cult classic of the genre and one of my all-time favorites (recently ported to iOS). But Stasis works independently of its inspiration, using the methodical, somewhat detached mechanics of the traditional graphic adventure in order to sow unease and encourage the player to slowly unfold the microscopic human dramas of its abandoned spaceship’s former crew.

The game is not perfect; it isn’t even my pick of best sci-fi horror game of the year. (That distinction goes to SOMA, which, I would argue, shares DNA with landmark first-person graphic adventures like Myst and The 7th Guest.) But this is exactly what is so exciting about being an adult in 2015 rather than a child in the mid-1990s: it’s not either/or. Games like Stasis are worthwhile not because there’s nothing else like them out there but because they are interesting in their own right, despite the competition; they have something to say and use their genre to say it. Graphic adventures aren’t topping many lists this year, but that’s okay; they don’t need the spotlight. What they need is an identity independent of nostalgia—a raison d’etre beyond being a throwback to a decades-past era—and this year has represented a major step in that direction.