The Year In Weird

I think I started writing about videogames because I was lonely. What I found in games was a sorely needed form of two-way communication. It started sometime in 2007 when I happened across the Indygamer blog (founded by Tim W., who I’ve now joined in doing similar work on Warp Door), which was regularly discovering and writing about these small, weird games that you couldn’t find anywhere else.

After a while, I started to recognize some of the recurring names of the individuals that were making these fascinating experiences. With some of these creators, it was possible to see themes across their oeuvre that collectively explored more than, say, mere mechanical experimentation. Making games seemed to be both a creative and a more personal type of outlet for these people, as if they operated like diary entries, providing insight into their thoughts and feelings as their lives played out. Noticing patterns in their work, spending more and more time with it, reading deeper and deeper, I started to feel attached to these people who I was able to concoct a vague impression of from playing their raw and experimental games.

these were the ones that spoke most to me

A few years after becoming absorbed in what evolved into a hobby, I happened across a desire to reach out to these people, who had only existed disembodied in my imagination. Yet, this impulse wasn’t realized in writing emails to these people, sharing my thoughts and thanking them. It felt weird to do that, as if I were a stalker unveiling my tainted presence in their lives. Instead, I started writing my thoughts on these videogames down, sending them into the chaotic void of the internet, just as they had done with their games. What made this compelling was that the ideas and emotions inside these games were usually crude and often communicated abstractly, meaning they came across as simply weird to mostly everyone, except if you were willing to look beyond that and connect the dots—yes, they were strange, but everything in these games had come from somewhere.

Five years later, I’m still doing the exact same thing, and I still care tremendously about games as a vessel for a person’s inner world, for them to eviscerate what’s bothering them, or to explore their thoughts on a complicated subject (all the while developing their ability and style in doing this). I tell you this so that you know how I’m approaching and presenting the games listed below. All released in 2015, these were the ones that spoke most to me, that let me into their creator’s mindspace and maybe also opened my eyes to something. In short, these were the games of 2015 that brought me closer to other people.

im null

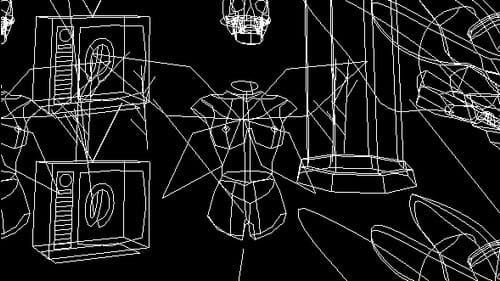

Thoroughly, but not unequivocally, im null is a virtual world about alienation. You wander as an indistinctive integer inside a black space, which is sporadically—and sometimes terrifyingly—scattered with concepts drawn in scratchy white lines. An endless highway, a woman screaming over the phone about a breakup, a lonesome drug trip, a graveyard; all these sights have in common the theme of exclusion (and are, themselves, distanced from players through their cryptic presence). Among them there sometimes wanders “null,” the shapeshifting skull that haunts this online space, banning the anonymous wanderers without mercy or reason.

It is into this eerie realm of nothingness that its lead creator, Zak Ayles, seemed to transpose an agony. In the months prior to launching im null he had tried to remove himself from the internet and escaped into his inner self for a while. His darkening thoughts must have slow-cooked during that period with this digital space bookending that process. And so what you might suppose about im null is that its title is a confession (both literal in that Zak might be playing as “null” inside the game, and metaphorically reflecting his state of mind) and the rest of the experience has been built to expand on that thought like an interactive monologue.

Play im null on Zak’s website or on Game Jolt.

///

Stick Shift

Stick grasped firmly, you stroke your hand up and down, not furiously but erotically. Small, rousing jerks. Long, teasing pumps. The car revs in excitement, accelerating into the ticker, ready for the next stage. You place your palm on the stick and fiddle it into the next gear and then… Tingling explosions of pleasure from head-to-toe, bursting, inside and all over the carburetor. Eyes roll back. Lips are bit. Exhausts drip.

Robert Yang has been exploring gay sex and erotica through games over the past year and more with the likes of Succulent, Rinse and Repeat, and Cobra Club. But it’s Stick Shift that stood out to me. An “autoerotica,” it captures both the excitement and the danger of gay sex and its relationship with technology. For me, someone of queer identity, it seemed to acknowledge my specific experience of finding vindication through a computer (the car representing technology in this allegory), specifically the media and community that helped me and that couldn’t have been reached otherwise.

Stick Shift speaks to an individual person’s non-straight pleasures

More than that, there’s a scene that has a 48 percent chance of happening in the game, in which a pair of armed cops turn up at your car window to disapprove of your open display of sexuality. They threaten authoritarian violence; something that queer people have known for centuries. Yang contextualizes this scene outside of the game as a call-back to the the Stonewall Riots in 1969, during which the queer community protested against the cops through flamboyance. And so Stick Shift speaks to an individual person’s non-straight pleasures (whether mine, Yang’s, or anyone else’s) but also to the historical troubles that queerdom has endured and, eventually, began to surmount. And, heck, it’s also goddamn arousing.

Download Stick Shift on itch.io.

///

Gardenarium

{"@context":"http:\/\/schema.org\/","@id":"https:\/\/killscreen.com\/previously\/articles\/the-year-in-weird\/#arve-youtube-yl3wum_auig","type":"VideoObject","embedURL":"https:\/\/www.youtube-nocookie.com\/embed\/yL3wUm_aUig?feature=oembed&iv_load_policy=3&modestbranding=1&rel=0&autohide=1&playsinline=0&autoplay=0"}

Vacationing in someone’s headspace isn’t possible but, if it were, I’d surely make the beautiful imagination of Paloma Dawkins one of my first stops. She emerged in blossom this year: I imagine her entrance to the medium as an image sewn in grass, her pose angelic, a delicate hand reaching out to a drooping petal, flower crown atop her head. Practised in vibrant animation, Dawkins made nature and everything it sprouts dance with her videogame work this year. She brought with her a distinctively bright palette, forgoing the expected choice of colors for each of her plants and trees to favor a motley intensity.

Gardenarium was her first, but there was also Alea, and that one is meant to be played with a moss controller. You place your hands in actual green lichens in order to play as if to symbolize the intimacy between human and verdure that Dawkins realizes on-screen. Gardenarium presents flora as a 3D stageshow; all singing, all dancing. Whereas games like Proteus and Eidolon portrayed nature as a grand tableau, trees and shrubs still and silent, Gardenarium brings it all to life in motion and song. It’s the people and creatures that are still, as if stunned by the sights as they grow around them, flashing and rippling in unison. In this place found on a cloud, you are safe and surrounded in beauty, able to chill and ruminate on the fabric of life. I get the impression that this is where Dawkins goes, in her head and through her art, to find peace.

Purchase Gardenarium through its website.

///

Strawberry Cubes

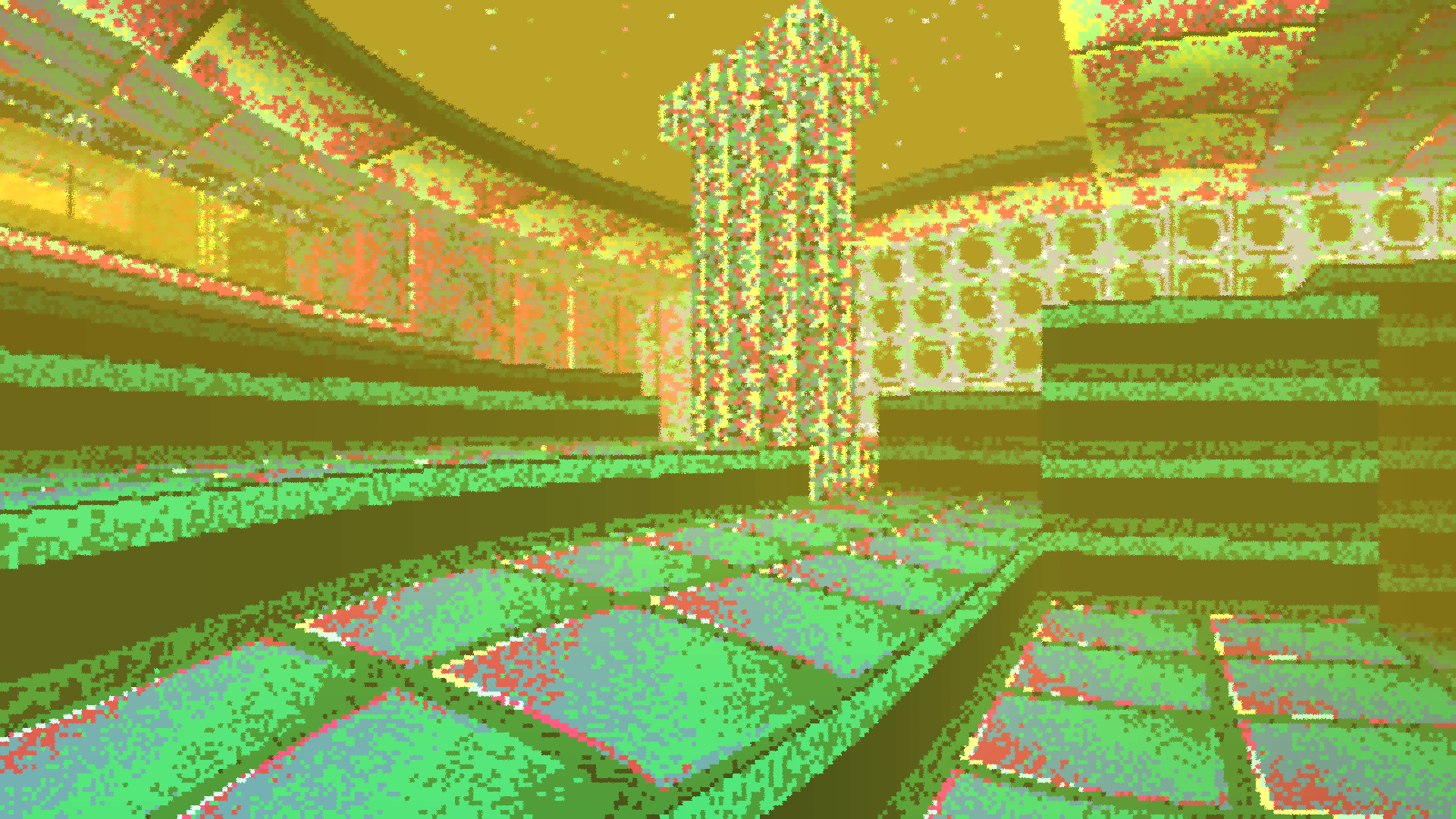

Loren Schmidt’s games are increasingly about texture and confusion. The two are interwoven. In Strawberry Cubes, you rely on the arrangement of sprites, the 2D mosaics of each room, to navigate. Ostensibly a trip through your grandma’s house, the game casts you inside a lo-fi labyrinth where the significance of icons and interactions have to be guessed at. Where are you trying to go? What are you trying to do? Nothing is known. There are skulls. There are frogs. There are numerous crimson icons flashing away. It’s all telling you something, you just don’t know what.

To wit, playing Strawberry Cubes is like loading up a save state in a videogame that you stopped playing months or years prior. You have to relearn what each button does and how its systems interact in ways that let you progress all over again. Except you don’t have that previous knowledge to draw upon. Your process ends up resembling cellular automata in that you attempt to find structure in the noise, testing out each process with each room, steadily grasping a workable map of this place and its rules in your head.

Schmidt’s interest in cellular automata is clear as he’s not only made a tool that lets him work with it but incorporated its evolutionary procedures into his games. Instead of a computer, he uses us as the inquisitive data, trying to make sense of the worlds he creates. Going forward, his next set of projects only further pronounce this interest, providing us with endless alienscapes to explore with the meaning and perhaps the rules being left for us to determine.

Purchase Strawberry Cubes on itch.io.

///

Hylics

Mason Lindroth released his masterwork with Hylics this year. His games are recognizably made in clay and animated with dithered stop-motion, this one especially so. Where his smaller projects before Hylics etched out specific curiosities and clay-monsters that he would re-use, it’s in this larger RPG that he really indulges his talent, bringing his previous work together under a single philosophy.

Hylics is about the malleability of material. You crush trash cans, mold clay sigils, throw highly-explosive dynamite and, when you die, also witness the flesh melt away from your face. Everything disintegrates, is molten, rapturously moving from one state to another as per the cycle of life and death. This is a celebration of the material world. It also sees Lindroth entertaining the playful tactility he so clearly loves and that is so desperately lacking in the digital game space. Hylics purports to be a journey towards spirituality but it is much more a testament to the glory of creation and destruction, which can only be found in the corporeal space that Lindroth so readily enjoys.

Purchase Hylics on itch.io or on Steam.

///

Knossu

Knossu is an experiment in non-euclidean architecture and it is terrifying. Instead of puzzles (although it is still puzzling), creator Jonathan Whiting sought to find the horror that’s possible within the limitations of tight corridors and unreliable geometry. It’s a reworking of his earlier game Knoss that adds structure to the concept while also expanding it to a fuller experience. Playing both of these games now is to condense the years between them and see the evolution of the idea as well as the progression of Whiting’s own skills. It all comes together like a perfectly composed nightmare.

Knossu benefits from two sources that its predecessor didn’t. First is the inspiration Whiting took from JP LeBreton’s notion of “Tourism play.” And second is Whiting’s own experiments in 3D level design. What we end up with is a frankly panic-inducing challenge: enter four separate spaces to bring a beam of light to a hub-like center that connects them all. The catch is that there’s some demonic and vague cloud of noise ambling in these areas. It warps your vision and sends alarm bells off in your ears upon approach and, if it catches up to you, warps you back to the hub. It’s not scary by itself, but consider that it’s so easy to get lost among Knossu‘s architecture as it shifts behind your back and catches you in sinister loops. The game is an accomplished investigation in pulling the rug from under the player’s feet and a true testament to developing a single idea to its maximum potential.

Download Knossu on Jonathan’s website.

///

Orchids to Dusk

{"@context":"http:\/\/schema.org\/","@id":"https:\/\/killscreen.com\/previously\/articles\/the-year-in-weird\/#arve-youtube-cwqamsu3qfa","type":"VideoObject","embedURL":"https:\/\/www.youtube-nocookie.com\/embed\/CWqamSu3qFA?feature=oembed&iv_load_policy=3&modestbranding=1&rel=0&autohide=1&playsinline=0&autoplay=0"}

No other videogame came close to matching the wordless gesture that rings out into the infinite in Orchids to Dusk this year. You may not discover it straight away as it’s hidden and requires a certain submission on your part. But it is entirely the point of it all. I speak of it vaguely so as not to spoil it but also because it has a poetry that averts articulation. What, then, can be said about Orchids to Dusk? Firstly, it’s a game that has you feel out the final moments of an astronaut after they crash land on a foreign planet, running out of breathable air. What happens to them might be up to you or, more likely, it has already been fated by the dire circumstance.

Secondly, it’s the latest game by Pol Clarissou. When he’s not making playful digital toys or beautifully goofy slapstick, Clarissou tends to make solemn, solo experiences that encourage us to think about death or, at least, the nature of existence. They’re quiet, visually pleasing, and contemplative pieces. You’re exploring space, alone in a subway, or daydreaming in darkness.

Orchids to Dusk follows on from this trend in Clarissou’s work as you are a lone astronaut left to explore a planet sparsely populated with oases and nothing more. But where Clarissou previously used procedural generation to provide an endlessness to his games, Orchids to Dusk has a determined end, and it’s in that the game’s power emerges. It’s a full-stop at the end of his work up until now, one that resonates through all our lives, across the planet, throughout existence. It is eternal peace and it is abject horror—it is what unites all of us.

Download Orchids to Dusk on itch.io.

///

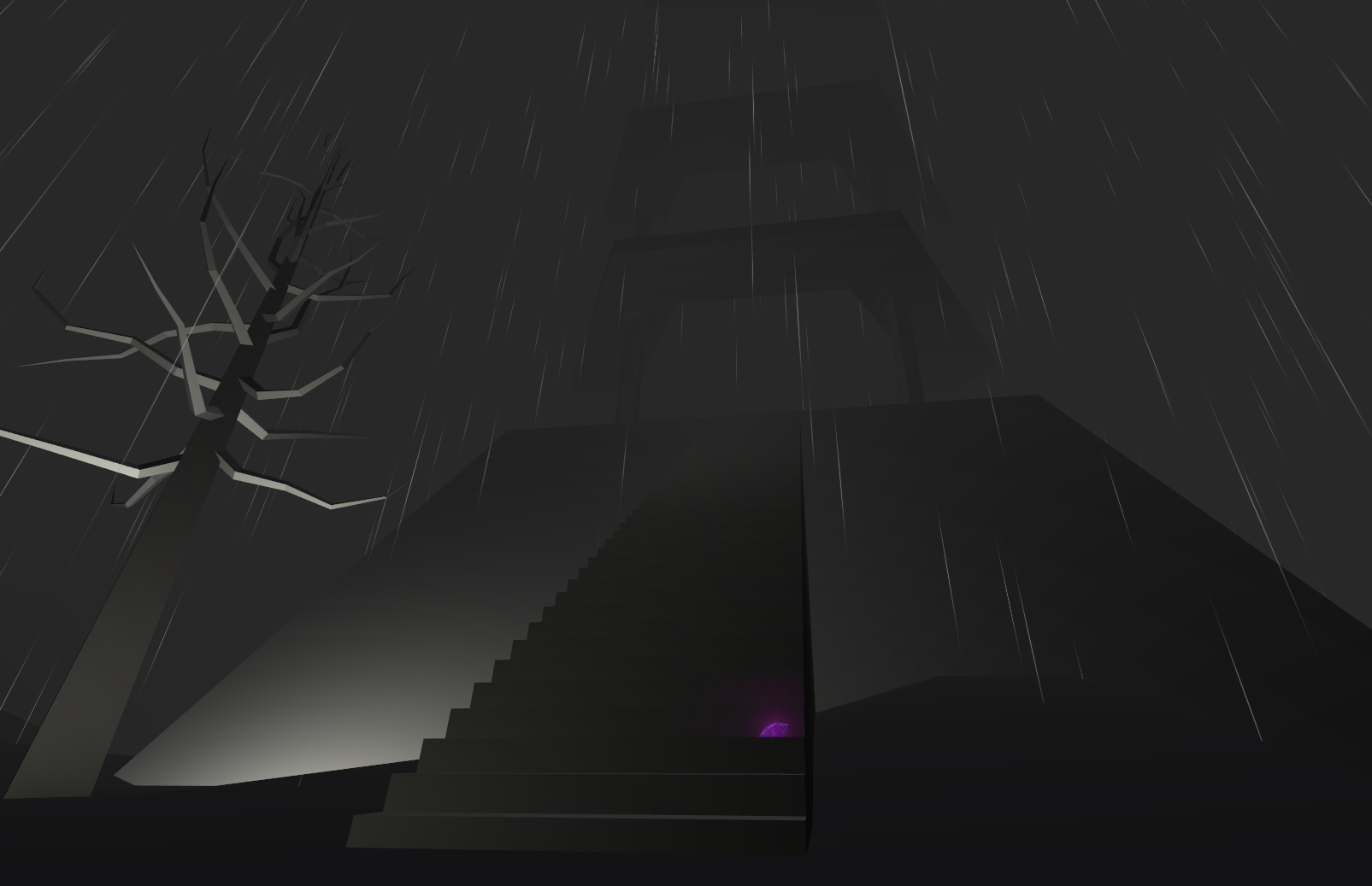

Rain, House, Eternity

Rain, House, Eternity is Kitty Horrorshow’s most personal game. It’s also the most implicitly distressing. And at the same time it’s the most hopeful. You wander through a series of intimidating architectural spaces in search of glowing purple gems. Pick one of these gems up and you get to read the thoughts of an unknown character who feels rejected by their family and the world. In short, they feel out-of-place, and it leads them to dark places where suicide doesn’t seem too bad an idea. Autobiographical or not, these snippets of monologue are certainly troubling, but it’s in pairing this with the surrounding chasms and enormous gray structures that Horrorshow excels.

She seems to acknowledge at a late point in the game the service that game creation has brought her. She specializes in crafting a specific kind of psychogeography. Her virtual buildings feel like individual people. They seem to talk to us in their silence. This is probably due to the emotional significance that Horrowshow grants them. She uses shape, line, color tone, and size to communicate her specific experiences of fear. And it’s in doing this that she seems to have broached and helped herself work through a number of tough personal matters. In Rain, House, Eternity she not only explores this but also reaches out to encourage us to find our own way of making peace where we need it.

Download Rain, House, Eternity on itch.io.

///

Selfie: Sisters of the Amniotic Lens

Gruesome at first, Selfie opens up after you’ve passed its early tests and turns into what can be a surprisingly touching community-based exchange. It starts with you sat in front of an old television, dead flies all around, a dismembered corpse staring at you coldly. After entertaining the masochistic beliefs of a cult and tapping into its black magic you’re able to depart this scene and head into cyberspace—it’s possible that you become one of the flies buzzing around the room you previously occupied. While it seems to then become a first-person shooter, the real heart to this game is found in the large floating bottles you can find in this new expanse.

These bottles are where the responses that new players typed out at the beginning of the game end up. “Shed your skin and tell me what lies beneath. What tears do you cry that are worth bottling?” the game asks upon opening it up. You can go as deep and personal as you like here but whatever you type will, technically, be visible to all other players, though not many of them will likely see it. Upon finding a bottle and reading the confession inside, you get the chance to “Condemn” or “Free” the writer, either taking away all their in-game currency, or giving them some of yours. If you choose the latter, you can also respond to their confession with a written reply (which, especially on the internet, is a freedom open to abuse), the idea being to offer this person your support in a more meaningful manner.

While creating Selfie, Dylan Barry was having theological issues that caused him to leave the church, while also growing increasingly paranoid. Given that the game acts as if an online confession booth but hides this underneath a nasty, uninviting preamble, it could be that Barry was working through his turmoil through the game’s themes. In any case, while it does contain religious ideas, it finds worth in a more universal gesture: encouraging people to help one another during their dark times, to mete out their sins and hopefully move on to a more positive space.

Purchase Selfie: Sisters of the Amniotic Lens on Steam.