The Year of Not Playing Games

This coming year, I will turn thirty-five years old. Such an accumulation of time brings certain privileges: the ability to run for President; the removal from key marketing demographics, aged 18-34, typically known as Young People; the necessity to buy shampoo that strengthens follicles at the root, “saving hundreds of strands per month.” When I entered that most trend-setting of audiences, way back in 1999, I did not foresee “playing and writing about videogames” as a key element of my identity in this far-flung future. And yet here I am, contributing to a year-end series about an industry whose evolution has shifted alongside my own throughout the course of its relatively short history.

But here’s the thing: I’ve squandered the last year of my marketable youth ignoring most of the videogames on most of the Best Of lists, including Kill Screen’s own. I could have kept up. I could have joined the conversation. But I didn’t, content to remain blissfully unaware of Solid Snake’s pain or Cibelle’s awkward romancing, because life beyond the screen proved challenging enough without any more lives lost. When asked to consider a theme or trend worth discussing, I could only think of an absence of themes or trends. For me, 2015 was the Year of Not Playing Games.

At least, that’s what I told myself and my editor. Then I checked the numbers. Turns out, I still played a ton of videogames. Less than previous years, yes. But the larger factor in my mental erasure of them had to do with perception. The games I played were not the ones I was supposed to have been playing. For some reason, they were not important enough, or new enough, or indie enough, or AAA enough, or obscure enough, or interesting enough to merit my attention.

I found two common denominators between those games I did sink time into: They were either on Nintendo systems, or were not released in 2015. The year started out strong, playing two award-winning games… from 2013. In January I fired up The Swapper, my New Year’s resolutions being transmitted metaphorically onto a 46” screen. I could be someone else this year, I thought, cloning and killing off multiple selves through the ten hours I played.

For me, 2015 was the Year of Not Playing Games.

I put 18 hours into The Legend of Zelda: A Link Between Worlds, GameSpot’s Game of the Year 2013, between February and March. Few of you out there, those reading this now, were talking about it anymore. But it was still good. I pressed Link into a two-dimensional painting on the wall and felt strangely whole. I must enjoy playing in the wake of past adoration. The last Zelda game I played on 3DS was another bypassed classic, the 3D remaster of Ocarina of Time I first experienced on the handheld. In my review, I list things my 17-year-old self was more concerned with at the time of its 1998 original release than playing a new videogame, among them my own two “spiritual stones” growing heavy with disuse. That’s one benefit of time, and being married: You feel confident enough to reference your testicles in a public forum without worry of recrimination.

You also can delight in the beauty of a pink blob artfully rendered in clay. By March, I put another ten hours into Kirby and the Rainbow Curse, this one at least current, though notably forgotten by the time December rolled around. Its charms are real, but our collective short memory is valid; for some reason the touch-screen puzzle-roller does not linger brightly in my mind, even though I enjoyed its thumbprint-stamped imperfection.

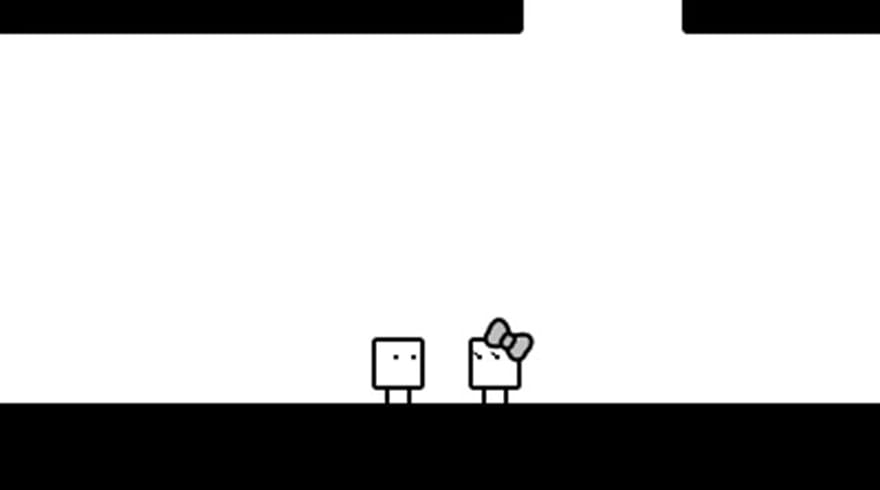

April brought with it another current game, but a small one, and one cut from such a simple, rudimentary mold as if to have been released in 1989. BOXBOY is a brilliant little exercise in avoiding excess. HAL Laboratory’s platformer does the most with straight black lines since the intercontinental railroad. How’d I forget the ten and a half hours spent throwing my square-head onto edges and reeling myself in? Perhaps the black-and-white aesthetic blurred my time with it into some pre-Oz-ian memory lapse. Perhaps the lack of a box on the shelf failed to remind me once end-of-the-year voting began.

That’s one regrettable consequence of our new all-digital consumption. Fewer physical goods mean less clutter, yes, and lighter boxes when moving across town. But as we read on our Kindles and listen to MP3s and play a digital file, foregoing the slip of a compact disc into a purring system, we grow disconnected from the thing itself—I experienced BOXBOY, but I didn’t place a cartridge in a slot. I can’t look across the room and see its spine alongside a collection of other games. When I felt like I hadn’t played anything this year, I must have meant something closer to this: I had not as frequently interacted with the tangible coverings that once meant “videogame.”

Come summertime, I did just that. A trio of Xbox 360 games have sat under my TV, wrapped in cellophane, for years: Fallout 3 from 2008, Bayonetta from 2009, and Child of Eden from 2011. While many sunk into their Steam Sale purchases, I caught up on past hits on old hardware. But more importantly, I displaced a physical disc from its plastic anchor and placed it on an extendable tray.

My layman hypothesis is contrasted by science, alas. Dr. Thomas Gilovich, professor of psychology at Cornell University, has studied how consumer goods and experiences affect our happiness. “You can really like your material stuff,” he writes. “You can even think that part of your identity is connected to those things, but nonetheless they remain separate from you. In contrast… We are the sum total of our experiences.” He’s referencing more active pursuits like traveling or visiting a museum. But to exist in a virtual world is one kind of experience. To own a plastic disc should not equal or trump what happens while there. Still, I wonder how downloading games will alter our memories of them in years to come.

But to exist in a virtual world is one kind of experience.

Awash in culture, especially as another calendar year folds over, we’re festooned with commands. Do this, listen to that, play this, watch that. And if we veer to the side of all this noise, the same noise that will be forgotten for the next wave of hype-riders in 2016, there’s a very real chance of feeling left out, or left behind. I can’t say how many times I hear or see another person expressing angst over not experiencing some heralded piece of culture. As an occasional irritation, the damage is minimal; “I should have ordered the soup instead of the salad.” But as a moment-to-moment drip of anxiety, the result feels closer to lunacy: An absence of reason, the opposite of reality.

When asked to consider their year’s experience, a suitable answer becomes, “But I didn’t play any games.” On Wii U (317 hours) and 3DS (123 hours) alone, I spent the equivalent of over seventeen days in front of videogames. But by and large, they weren’t what others in the enthusiast, alternative, or mainstream press were talking about. Drip, drip, drip. The erosion leads to valleys where before there was a mountain.

The James-Lange theory suggests that our experience of emotion is actually an experience of bodily change as we perceive that emotion. We don’t run away because we are afraid; instead, we are afraid because we run away. C.G. Lange, a Danish philosopher, developed the theory in the mid-18th century. Elsewhere, William James theorized the same notion, independent of Lange’s work. Today their names are connected as if having worked in tandem. But the truth is they conducted their own research and only later saw that another felt the same.

It is increasingly difficult to remain untouched by others’ opinions. By the time you play a particular game, or see a film, or read a book, you likely know how thousands before you felt. But resist the temptation to have such opinions narrow your field of view. There’s little sense in crowdsourcing a Rorschach test. The ink-blot awaits you, its wavy contours a mystery, whether translated now or in ten years.

//

Header image by fotologic via Flickr

Rorschach Test photo by Zeh Fernando via Flickr.

Old Man photo acquired via Wikipedia Creative Commons.