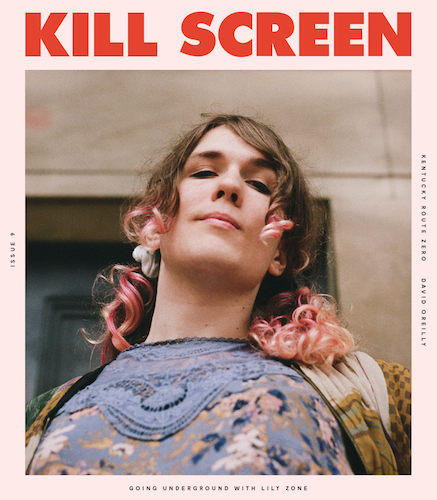

Header art by Gareth Damian Martin

“Is it esports?”

This questions comes up, both honestly and facetiously, about a huge variety of games. Sometimes, esports is a groundswell, a way to mark the community that gathers around competitive games they’re passionate about. Other times, “esports” seems more like a trope or a marketing tool. With each passing invocation, the term fades from grassroots communities and inchoate competitive cultures to grand arenas, massive paychecks, and a litany of sponsorships.

Yet in the wake of the huge growth in esports over the last half decade, there are still surprises, such as the curious case of competitive Catherine (2011). A puzzle game conceived as a side-project for the team of developers working on the Persona series, Catherine isn’t exactly anyone’s idea of an esport. But, in time, the game has proved itself compelling enough to gather a community and it has begun to appear at tournaments around California’s fighting game circuit.

“Catherine isn’t exactly anyone’s idea of an esport.”

Catherine, as most people know and play it, tells the story of a man torn between two women, a narrative interspersed with symbolic episodes of climbing towers in his nightmares. In the game’s story mode, the towers represent his frantic climb, and by pushing and pulling blocks to climb on, you can make structures to climb away from the crumbling base of the tower, while avoiding trap blocks like bombs and spikes. After beating the game, a multiplayer mode is unlocked, where two sheep-men race to the top of the tower in a best-of-three match.

The two players who conceived competitive Catherine, David “Dacidbro” Broweleit and Sean “Coopa” Hoang, initially picked the game up on a whim one evening.

“We booted [Catherine] up at midnight and [then] we realize it’s like, 7 a.m., and we don’t understand where the time just went because we got super-sucked into this game,” said Broweleit. “We were like, ‘we have to learn how to play this.’”

The two are members of the northern California fighting game scene, and focus mostly “anime fighters”, a sub-genre of fighting games rendered in anime’s distinctive art style. Games like Guilty Gear Xrd Sign and Persona 4 Arena Ultimax share many visual similarities with Catherine, so when the organizer for a tournament called Norcal Install was looking for a new side-tournament, where participants could compete in a less intense, non-main event game, David and Sean introduced them to Catherine.

It was an instant hit.

“Everyone rushed to complete the hardest story mode difficulty in Catherine as practice,” said Hoang. “In particular, James Xie and TLoc were noteworthy [competitors] from Socal. They brought a lot of hype to Super Norcal Install, a glorified version of NCI where people from a lot of different regions competed.”

At first, the meta-game of Catherine seems distant from fighting games. Instead of two combatants exchanging blows on a 2D plane, Catherine is a 3D block-climbing puzzle, where victory can be achieved without actually fighting your opponent. Racing to the top can ensure your victory, but so can hindering your opponents progress. As a result, many Catherine players will spend as much time trying to impede their opponent’s progress as they do ensuring their own.

“I always had trouble being a good builder, but as a defensive player, I liked getting a head lead and forcing my opponent into road block situations with ‘option-selects,’” said Hoang. “Or, in Catherine terms, pulling or pushing out a block that built a solution while also obstructing an opponent.”

“Take all the board theory of chess and put it into a fighting game; that’s how Catherine works.”

This creates a dichotomy between two approaches to playing Catherine: the “builders” and “fighters,” as Hoang describes them. You can knock about your opponent with a pillow, but beyond that, most of the combat of Catherine is area denial or control. As the bottom of the tower falls out, holding the high ground is of the utmost importance. You also have to factor in stage selection and block types; both players likened Catherine to Super Smash Bros, in that stage selection can be as important as personal play. Knowing the layout and blocks you might run into can mean the difference between executing a well-laid plan or climbing blind.

“You take all the board theory of chess, and put it into a real-time fighting game, and you’re getting kind of close to how Catherine works,” said Broweleit. “You spend a lot of your time rigging the board either in your favor, or just in a way that your opponent wouldn’t be aware of or familiar with, and using that to kill them.”

“We have to learn how to play this.”

It’s cerebral, to be sure, but it’s still a duel with plenty of mechanics that can force opponents into compromising positions, which forms the basis for the strategies that animate the game when it’s played competitively. As both Hoang and Broweleit note, Catherine may be most well known as a darkly comic puzzle game, but its multiplayer mode utilizes many concepts that fighting game players are accustomed to. Shimmies, option selects, frame traps and more made Catherine an natural fit for the fighting community, and it immediately became a cult hit at tournaments.

“I think Catherine was just a good example of the right game at the right time,” said Hoang. “It came out when the our scene was still developing, and it also came at a time a lot of the core players in our scene wanted to shine. Our quirks, our strengths, and our personalities really melted over into other games, and Catherine was a hilarious battleground for that.”

The birth of competitive Catherine culminated in a spot at EVO 2015 run, where publisher Atlus featured the game amongst its lineup in Las Vegas. While still a side-game, Catherine was being featured on an official stream, with thousands watching as the grand finals took place. In a tense matchup, Broweleit defended his title, showcasing the clever intricacies of high-level Catherine play.

It was a watershed moment. But as Broweleit puts it, it wasn’t the moment.

“Right now we’ve more just tried to maintain since last year,” said Broweleit. The community has experienced some growth since Super Smash Bros. Melee player Kris “Toph” Aldenderfer started playing and streaming, but it’s not quite at the level of titans like Melee or Street Fighter V. Because the game is limited to local play, it’s difficult for players to even get in the amount of practice necessary to elevate the game to higher levels. It’s a struggle that even Melee has had to cope with by creating pseudo-workarounds or relying on a network of local scenes to grow the community, but it’s difficult to get a smaller game like Catherine the prevalence that would alleviate these issues.

“I could genuinely make this game take off.”

“The Catherine community has been kind of cursed to basically live at tournaments, just because there’s so few people and no net play,” said Broweleit. “But if all the good scenes can get one or two people locally to play, that would really help.”

In an age when most competitive games live as much online as they do at LANs, Catherine is limited by the demands of physical gatherings. Hoang also spoke to the issues of a community that only blossoms at live events, saying that “in Catherine you’re only as good as your competition around you, so it’s difficult to see the scene progressing.”

Having online play wouldn’t just guarantee high-level players an opportunity to practice without jumping on plane; it would welcome new players, who might be too intimidated to approach a growing crowd at a tournament, but could practice over the internet at home and hone their skills without the anxiety of performing in front of a crowd. Broweleit also echoed sentiments of the power of net play in competitive games.

“If we could have netcode for this game, and actually have net play, I could genuinely make this game take off,” said Broweleit. But he continues on to praise the quality of the game, and its lack of exploits or general imbalance, calling the game “self-sustainable.”

Both Hoang and Broweleit theorized that a Catherine 2 would be the chance for this game to elevate in the ever-changing pantheon of fighting games. It also raises an issue, though, with whether you could ever replicate this kind of game.

Catherine is one of the more modern examples of a cult-classic game, using stylish art direction and clever puzzles to explore the relationship of a man caught between two women, one of who may-or-may not be fictional. It’s all very unorthodox, with two sheep-men climbing blocks and slinging pillows at each other, but its mix of tower-building strategy with fighting game mechanics lend surprisingly well to engaging, tense competition. Its appeal as a grassroots uprising is intoxicating, especially amongst (and against) a sea of unreleased games billing themselves as “esports” on the day of their release. Catherine forged a community without marketing itself as the “next big thing”; its competitive scene was born of a passion for the kind of fun only Catherine offers.

“The problem is that Catherine is kind of bizarrely unique.”

“The problem is that Catherine is kind of bizarrely unique,” said Broweleit. “All of the charm of the game is very important, the physics engine is very unique and would be very difficult to replicate well.”

It’s the kind of game you want to be wildly successful, filled with groundswell passion and love for the game. Catherine was, by all accounts, never intended to be a competitive game. Yet in 2016, five years after its release, it is one of the most hotly anticipated side-tournaments at the biggest fighting game event in the world. Players may struggle to keep the scene thriving, but once you’ve seen it played, frankly, it’s hard to shake. It may never grace the main stage, but the quirky, brilliant Catherine is a true symbol of the power of grassroots communities in esports.