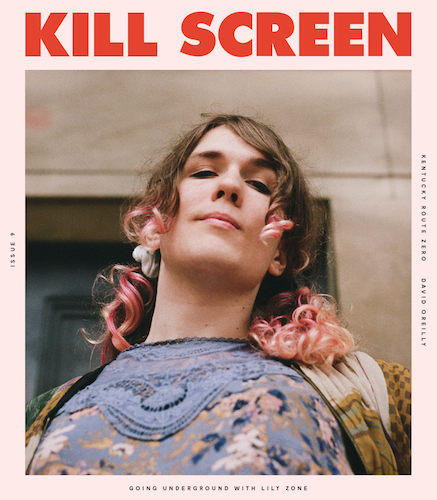

Header illustration by Gareth Damian Martin

If you ask YouTube content creator Verlisify, there’s a cancer eating away at the heart of competitive Pokémon. Verlisify, whose channel has over 200,000 subscribers, is the most prominent crusader against a form of tool-assisted play he claims runs rampant throughout even the highest levels of The Pokémon Company’s (TPC) official World Championship circuit.

“A majority of all [competitive] Pokémon players cheat,” he tells me via YouTube message, “and I wouldn’t be surprised if the number is over 80% … two of the Top 4 European national champions admitted to using hacks on Twitter, as well as a majority of the US Top 32 players.”

It’s a serious accusation. In Counter-Strike: Global Offensive, players like Hovik “KQLY” Tovmassian have been permanently banned from competitive play for hacking. Using third-party applications to cheat in multiplayer videogames is typically enough to get even casual players banned. For professionals, it’s a career-ending offense. Many of Verlisify’s videos show alleged proof of top players using hacked (i.e., generated artificially rather than caught in-game) Pokémon. You might expect that the broader competitive Pokémon community would appreciate Verlisify’s whistleblowing. But when I Google “Verlisify YouTube,” the second result is a video titled “Verlisify is an Idiot,” from fellow Pokémon master Pyrotoz (59,000 subscribers—who knows if these subscriber counts mean anything, but since they’re the metric we have, I’m going to provide them where possible).

“In the six years I’ve spent on YouTube,” says Pyrotoz in a debonair British accent (he looks like a debonair British lumberjack, if we’re honest), “I think that Verlisify is probably one of the most stupid people I’ve ever encountered.”

Verlisify is aware that not everyone sees things from his perspective. “VGC hates me and I don’t like them,” he says, referring to the “Video Game Championship” community that competes in TPC’s official circuit. “Far too much corruption. Too many players support hacking and just have a toxic mentality that disgraces the spirit of the game.”

It all gets rather convoluted and migraine-inducing

Leaving aside the bidirectional hyperbole for a moment—both of these guys, at the end of the day, are entertainers on a platform hardly known for its rhetorical subtlety—it’s clear that there are serious and emotional disputes within the Pokémon community. (Somewhat humorous reminder that this is Pokémon we’re talking about, a game for all ages, with characters based on teddy bears and ice cream cones.) What seems like cheating to Verlisify strikes others as a reasonable time-saving measure. Pokémon does in fact have anti-cheat software, but it’s only intended to detect ‘mons that are straight-up illegal (e.g. a Bulbasaur with 999 in every stat, Dark Void, and Draco Meteor), not those with stats, abilities, and moves within the bounds of what’s achievable through normal play. Why bother hacking if you can’t unlock anything better than what’s available in-game?

Prepare for far more detail on the inner workings of Nintendo’s venerable monster catch-em-up than you ever intended to know. First, every Pokémon has six stats: attack, defense, speed, etc. When a Pokémon is generated by the game engine, it is assigned a random value between 1 and 31 in each stat; these IVs, or individual values, determine the specimen’s strength relative to other members of its species. Each ‘mon also has a Nature, which raises one stat by 10% and reduces another by 10%; there are 25 Natures in total. The probability, therefore, of catching a totally perfect Pokémon on your first try, with IVs of 31 in every stat plus the correct Nature, is 1 in 22,187,592,025. Since this is impossible (duh), the developers added a complex system called breeding that allows you to slowly work your way toward perfection over a long period of time and many generations of forced Pokémon reproduction. Breeding a perfect Pokémon takes maybe eight hours if you have all the correct tools, which themselves are not easy to obtain (hello perfect IV Ditto), and you have to do it for every ‘mon on your team. It’s extremely grindy and repetitive, with much riding back and forth on your in-game Bike to hatch eggs, then flying your newly-hatched babies across the map to the guy who tells you—one ‘mon at a time, one stat at a time—what their IVs are, then back to the ranch for more riding back and forth. Repeat for eight straight hours. But if you’re a competitive player, you probably want to experiment with a whole bunch of strategies and lineups—there are 700 different Pokémon, after all—and when you add the hours of training required to get even a flawless baby Pokémon into final competitive shape, you start to see why people are incentivized to hit a button that saves weeks of playtime and generates those suckers right on the spot.

Plus, when it comes to preparing a team, the serious Pokémon competitor can’t settle for anything less than perfection. On the VGC forum Nugget Bridge, I find a thread on catching flawless Legendary Pokémon, a process made particularly onerous by the fact that you can’t breed them, which means you have to keep restarting your game over and over to try and spawn an acceptable one. Although at least they’re guaranteed to have 3 perfect IVs, and you can control their nature with an ability called Synchronize, improving the probability of finding a perfect ‘mon to something like 1 in 29,000—sorry, it all gets rather convoluted and migraine-inducing.

As the creator of the thread observes:

“I get a lot of people asking me why I bother getting all perfect IVs instead of just settling for 27+ IVs, and the answer to that is pretty simple. We play a game where luck plays a big role … By settling on a Pokémon with imperfect IVs you are making yourself more vulnerable to luck … Have you ever lost a game because your Pokémon got KO’d by a move that had a 1/16 chance to KO? Using imperfect IVs opens the door for that to happen … as a competitive Pokémon player, I will gladly spend more time resetting for a Pokémon with ideal IVs than settling on something less than optimal.”

I ask Verlisify what he thinks about all this—whether maybe it’s too much of a grind to expect from competitive players—and he shrugs it off.

“I think the investment to get competitive Pokémon is perfect right now,” he tells me. “Every competitive game demands some form of sacrifice.”

In a way, he’s right. All esports challengers sacrifice countless hours to achieve success. But that grind is typically to improve skills, not unlock tools. And Pokémon championships don’t go to the person who breeds the fastest, or catches a perfect Mewtwo in the fewest soft resets. Championships go to the person who’s best at using a team of Pocket Monsters to smash the opponent’s team of Pocket Monsters into a scatter of colorful kibble.

What’s really at stake here isn’t so much a question of ethics as it is a fundamental disagreement over what competitive Pokémon should be. Purists like Verlisify advocate for holistic competition, where victory depends as much on breeding and training as it does on tactics. VGC competitors believe that battling itself should be the focus; for them, the team-building grind can be a tiresome distraction.

Still, Verlisify and the tool-assisted players at least agree that competitive play ought to take place on genuine copies of the game. For a third faction, members of the strategy forum Smogon.com, even this point is up for debate. Smogonites compete on a third-party emulator called Pokémon Showdown, which strips away all the series’ nonessential elements, including catching, breeding, and training, leaving only the player-vs-player arena. For Smogonites, who are used to artificially generating their teams online, the debate over cheating in VGC seems almost meaningless.

In 2016, the interplay between these camps is more interesting than ever, because the competitive Pokémon scene is growing with Rapidash velocity. TPC enlisted seasoned tournament organizers ESL to run their professional circuit this year; on August 8 they announced a 2017 season with $250,000 prize pools at each major event. That puts Pokémon on track to exceed StarCraft II in terms of annual prize money, which would have been unthinkable even three years ago. It also puts these three factions—Verlisify-style purists, the VGC community, and Smogonites—in the position of competing over whose definition of competitive Pokémon will wind up becoming the official stance.

The squabbles have already begun. Aaron Traylor, runner-up at this year’s US Nationals, tells me that voices around the world are prone to “whining and complaining” about the competitive infrastructure put in place by TPC.

“I would recommend against going in depth on this question,” he warns me, “because there are some very loud negative voices.”

Curiosity piqued, I demand more details on the complainers and their complaints.

“I really don’t want to talk about either of those things, sorry,” he replies tersely. “I’m sure you can find other people who have strong opinions on the format.”

If you’re wondering why tournament format could be a divisive topic, sit back and prepare for another info dump. Some videogames, like Super Smash Bros. Melee, are more or less competitively playable right out of the box. Pokémon is not one of those games. The difference is that an unregulated Melee metagame boasts a variety of characters and strategies, ranging from methodical Foxes and showstopper Falcos to slippery Luigis and bombastic Captains Falcon, whereas an unregulated Pokémon metagame would probably mean six Primal Groudons squaring off against each other endlessly into infinity. There are 700 Pokémon, but ten or twelve of them are so much better than the rest that an equilibrium point with zero strategic variation would soon be reached. But it’s not in Nintendo’s, and therefore TPC’s, DNA to fine-tune and patch their games for competitive purposes (the relationship between the two companies is so complex, by the way, that it confused investors into mistakenly adding billions of dollars to Nintendo’s stock valuation after Pokémon Go’s release). So TPC’s efforts to define a fair ruleset tend to utilize the broadest strokes possible: “no box-art legendaries,” or in the 2016 ruleset, “only two box-art legendaries per team.”

The players, in other words, balance their own game

The result: most teams at this weekend’s World Championships will feature a Groudon, a Xerneas, and either a Mega Kangaskhan or a Mega Salamence. Many teams will abuse Moody Smeargle, a Pokémon that can learn every move but at Worlds will stick to the same five or six. Some folks will mix it up and throw in a Kyogre or Yveltal instead of a Xerneas. Others may try extremely crazy stuff to catch their opponents off guard. But for the most part it will be Groudon and Xerneas vs Groudon and Xerneas, Groudon and Xerneas vs Groudon and Xerneas … Groudons and Xerneases—Xerneai?—all the way down. Matches in this metagame are decided by factors like whose Groudon is faster, which again puts the onus on players to build superlatively perfect ‘mons (read: cheat). A single missed attack (Precipice Blades, Groudon’s calling card, has a lackluster 85% accuracy rate) can decide an entire game. I love Pokémon, but even I don’t find these matches tremendously fun to watch, and I have a hard time seeing how they could be particularly fun to play.

Broadly speaking, everyone agrees that the ruleset needs work. It’s the solutions that are contentious. Verlisify and his ilk argue that eliminating cheating would lead to greater variety by giving less-inherently-powerful but better-trained ‘mons a chance against foes with more built-in firepower but lazier training. Many VGC players would be satisfied with the simple expulsion of box-art legendaries and Moody Smeargle. And the gritty online battlers of Smogon and Pokémon Showdown have developed an elaborate system to fix the stale metagame on their own, centered around “tier lists,” which ban overpowered Pokémon to enable others to thrive.

For a perspective on the Smogon system, I speak to Joey “PokeaimMD,” a prominent battler and personality with 126,000 YouTube subscribers. Joey is a man of explosive energy and hummingbird attention span; our Skype call is punctuated by mouse clicks and bursts of typing that I’m pretty sure he thinks I can’t hear. Joey opts not to share his last name and can’t remember the exact title of the major he’s pursuing at college. It’s clear that for him, Pokémon is serious business. He bristles at the very mention of tier lists.

“I never understood how people would say: ‘oh man, don’t play by Smogon rules, because these Pokémon are banned,’” he says. “Yes, there are Pokémon that are banned, but you can still use them in specific tiers. If anything, Smogon makes it easier to use your favorite Pokémon.”

You can tell it’s a question he’s fended off before. (Verlisify, for instance, is a dogged and vocal detractor of tier lists, making him as unpopular among Smogonites as he is among the VGC devotees.) I see how it would be confusing: “your plan to increase my freedom to pick Pokémon is to decrease my freedom to pick Pokémon?” It’s a Hobbesian argument, essentially: submit to a governing authority and surrender the right to abuse your neighbor with Groudon and Xerneas. In the absence of such tyrants, the metagame blossoms, creating a boundless cornucopia of viable teams.

He gives the example of Vaporeon, which while borderline useless in unrestricted competitive play can be a major threat in the Under-Used tier (UU), where it faces foes of similar strength.

Satisfied, I try to move on to the next question, but Joey isn’t finished: “One more thing I wanted to add: yes, certain things are banned, however a lot of this is voted by the community … I know for example in VGC, everybody wants Smeargle gone, because Smeargle is ridiculous … but then The Pokémon—or Nintendo, or whoever—The Pokémon International, or—I’m not sure, necessarily, who goes over it—they’re not doing anything about it. Whereas here, if enough people complain, we’ll have a suspect test for it, where we can determine, after a set amount of time, whether it should be banned.”

The players, in other words, balance their own game. Can you imagine a game like Dota 2 or League of Legends being balanced by its community? Sounds like a recipe for unbridled vitriol and chaos. And it’s true that some of Smogon’s suspect tests get heated. Every time a Pokémon is banned on Smogon and Pokémon Showdown—i.e. sent from “Overused,” the prime competitive tier, to “Uber,” the land of Groudon and Xerneas—somebody on the forum becomes unspeakably pissed off. (“If You Think Blaziken is Uber, You are a FRAUD,” reads one thread from 2013 that was summarily closed by moderators.) But the community soldiers on, somehow, and at this point they’ve been soldiering on for years, rebuilding their tiers with each new addition to the Pokémon franchise.

Joey’s fiery defense of tier lists leads me to believe that he’ll have strong opinions on Smogon’s rival factions. Naturally my next step is to try and goad him into taking potshots at the VGC format. There are plenty of reasons to expect him to feel at least middling disdain towards TPC’s competitive creation: VGC is double battles, whereas Smogon tends to focus on single battles; VGC hogs the esports spotlight, with thousands of dollars in prize money, whereas Smogon-format champions are lucky to walk away with a $50 gift card; and plus there’s the basic “you like something different from what I like” animosity that keeps MOBA fans at each others’ throats 24/7. To my surprise, Joey approaches the question with caution and tact.

“The only thing I would do,” he says slowly, “would be ban Smeargle, and keep VGC pretty much the same.”

Pause.

“So you’re totally happy, in other words, with all these legendaries?” I ask.

“Ahh,” he says, sounding physically pained, “not necessarily.”

A few days before speaking with Joey, I’d interviewed Aaron “Cybertron” Zheng, a two-time US National Pokémon Champion, 2013 World Championship bronze medalist, and all-around VGC coolguy. My efforts to stir up shit with Cybertron had proved equally fruitless.

“Do you think there’s a chance,” I asked Cybertron, “of the VGC and Smogon communities coming together in some way? Compromising on a ruleset?”

“I think it’s hard,” he replied. “I think the main question should be how to sell these guys on why VGC is such a great format. Little bit harder to do when this year is one of the more unappealing formats. But if we have a good ruleset—I used to play singles, but I find VGC just so much more interesting and fun.”

This was the kind of bold statement I was after. All I needed was a quick, patronizing dismissal of the Smogon system, and the stage would be set for a staggering clash of diametrically opposed Pokeworldviews—

“…the thing that Smogon does is obviously balance their ruleset. Some people are a fan of that, others aren’t—”

Here we go, I thought, expecting him to call Smogon’s system presumptuous and excessive.

“—but I liked that, because it feels almost as competitive as can be,” he said, surprising me with his diplomatic tone.

It’s odd, but the closer I look, the more it becomes apparent that VGC and Smogon, for all their differences, are two sides of the same Bronzor. Nothing illustrates this point more than the discovery that Joey and Cybertron are actually old internet friends, that Joey intends to compete in VGC events in the future, and that the two of them not only met up at a regional tournament this summer but carpooled across half the Eastern Seaboard afterwards.

It’s inevitable that someone will wind up disgruntled

In Cybertron’s view, Smogon isn’t a competitor to VGC, because their player bases are interested in different things. He tells me he wouldn’t expect Smogon’s format to become a separate esport, because players who prefer serious competition tend to choose VGC in the first place. I imagine that there are plenty of Smogonites who would disagree with that, who would in fact be quite appreciative of OU Pokémon Showdown tournaments with $250,000 prize pools, but considering the unlikelihood of that scenario, maybe it’s a moot point.

The major obstacle to Smogon’s brand of Pokémon competition becoming a full-fledged esport is that the Pokémon Showdown emulator on which it runs is unauthorized by TPC and therefore presumably a textbook case of copyright infringement. Were tournaments in Pokémon Showdown ever to grow to the point that they pulled viewers away from VGC, it’s not hard to imagine TPC cracking down. So far they’ve left it alone, probably because people use the service not as a replacement for but as a supplement to the cartridge games. It would be hard to find a serious Pokémon Showdown user who does not intend to purchase every upcoming game in the series. But Nintendo does not have an especially strong track record of leaving prominent fan projects in peace. When fans attempted to de-casualify Super Smash Bros. Brawl through a mod called Project M, Nintendo let it slide for a while, but as soon as the esports scene took off, they intervened to prevent tournaments from streaming it.

I ask Cybertron and Joey if they think TPC might crack down on Pokémon Showdown, and neither of them seem particularly worried. Cybertron points out that many VGC players use the online service to practice. Joey thinks TPC would be more likely to go after ROM hacks, which compete directly with the single-player gameplay of official releases. As an occasional Pokémon Showdown player, I hope they’re right. At the same time, part of me can’t help but remember that fans of Project M never saw their game’s demise coming either.

Fears for the future aside, the atmosphere pervading today’s competitive Pokémon community is one of heady optimism. This weekend’s World Championship promises to be the biggest Pokémon event yet. Cybertron has given up his competitor’s berth to help cast the tournament; Joey, who didn’t attend enough events to qualify for competition, will be there to spectate and meet up with fans. After a champion is crowned, attention will turn to the announcement of the 2017 VGC ruleset, coinciding with the release of Pokémon Sun and Moon in November. This ruleset may be the most hotly anticipated in Pokémon history, with players all over the world nursing hopes for significant change. Since the changes they’re hoping for are often contradictory, it’s inevitable that someone will wind up disgruntled. Example: when The Pokémon Company announced that Sun and Moon would for the first time introduce the ability to improve Pokémon IVs, pleasing many players by reducing the need for time-intensive breeding, Verlisify hated the idea. Even in disagreement, though, there’s only so far the community will splinter. When you love the living shit out of an esport that most people consider a children’s game, anybody who shares your passion is on your team.