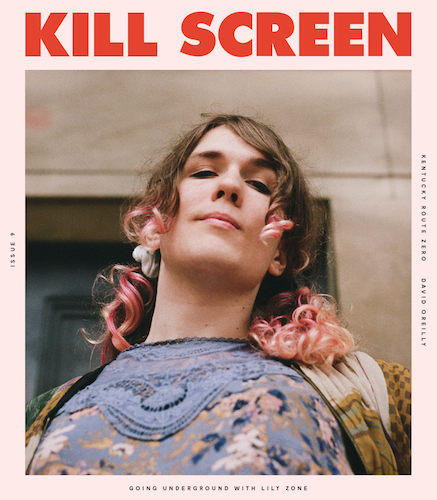

Header art by Gareth Damian Martin.

“An athlete cannot run with money in his pockets. He must run with hopes in his heart and dreams in his head.”

This quote, from Olympic long-distance runner Emil Zátopek, touches on the monetization of athletics. When an athlete breaks into their field, they become a face that brands can put labels and logos on. In the mythic version of this story, they start with little and push to the top, punching frozen hunks in the meat locker to train for their big day, so they can start punching real bags.

Athletes benefit from better equipment though. Stories of perseverance and determination populate the mythology of sports—the Rocky’s of the world inevitably say they can push through on force of will alone—but the truth is that athletes train and perform better when they have the best tools to do so.

Esports is no different in that regard, but here an investment isn’t just recommended; it’s necessary to even start training.

Esports has a buy-in problem.

Esports has a buy-in problem. It’s an issue inherent to the medium, but one that aspiring competitive gamers have to cope with, and can make or break a player solely based on factors that can’t be solved with extra mornings at the proverbial track. Esports has a cost associated with being competitive, one many could find themselves unable to pay.

The majority of competitive games are free-to-play. The heavy-hitters, such as League of Legends, Dota 2, Hearthstone: Heroes of Warcraft, offer completely free downloads of their clients, and players can start a match almost immediately. Others, though, like Counter-Strike: Global Offensive and Street Fighter V cost an up-front fee to own the game and start playing with others.

At first glance, the free-to-play system is enticing. There’s no initial investment on the player’s end beyond hard drive space, and it’s easy to convince other friends to try it as well. These days, it’s possible to download a new game and be playing within 15 to 20 minutes, happily rolling down mid lane, learning all the in’s and out’s of last-hitting and pushing a Nexus like the best. Well, maybe not the best, but the idea is that anyone can get there, someday, with the requisite amount of practice.

But what happens when someone actually wants to get there, to actually be the best? After some time, a new player might be watching the League Championship Series and think, “I want to be the next Bjergsen.” Many probably do, or at least attempt to play at a high level in League and other games. To do so, they need two things before they start climbing ELO mountain: a decent pool of champions, and some rune pages.

Since League of Legends is free, there’s a free champion rotation every week; but all other champions have to be purchased with IP (gained through playing games) or RP (a real-money-purchasable currency). So what’s the cost of owning a decent pool of champions in League?

Well, for a completionist, it’s steep. It is physically possible, but the time investment is extreme if a player wants to own all the champions in League of Legends. Let’s say a player does three 37-minute games per day on Summoner’s Rift, and wins all three. Per Riot’s own metrics, an average player would earn 450 IP a day in this scenario.

What’s the cost of owning League?

The cost of every champion in the game, through IP alone? 508,200. So it would take that player roughly 1,129 days to reach at that rate, and that’s only if they win every single one of their 3,387 games, while also assuming no new champions are released for the three years it would take him. An average game of League takes a minimum of 20 minutes, so that’s already generous, considering it can often take upwards of 40 minutes or more. The 125,319 hours the player would spend on League alone, at 111 minutes a day with not a single day’s break, would have to be completely lossless, or even more hours would get tacked on.

Of course, there’s RP, which lets players subvert the time-grind with real-world money. The best way to do that would be to buy $100 bundles of 15,000 RP apiece, as the RP cost of every champion adds up to a whopping 101,903. On sale at 50 percent off, that’s a little over $300; at full-price, closer to $700.

This isn’t accounting for rune pages either, a necessary component to playing competitive League of Legends. Using a handy rune page calculator tool and some basic Tier 3 rune pages written by the staff over Dignitas’ website, it would take another 123 days at the aforementioned 111 hours-a-day rate to reach the 55,350 IP needed. That’s only for five basic rune pages for each role in the game.

League of Legends is not alone in demanding a significant investment of time or money from players who want to play competitively. Hearthstone is popular amongst amateurs and professional players, but the cost to play at a competitive level has continued to rise over the past couple years. Purchasing just the Adventure sets needed costs $50, or 7000 gold, which is equivalent to 2100 wins. Then there’s card packs at 100 gold each, or $40 for 50 if the buyer is thrifty. Packs also give you random cards, and never guarantee a card someone might be looking for—just more Dust to inefficiently craft the desired card if a pack doesn’t yield it.

Even Street Fighter V, a $60 game, costs extra time or monetary investment to own all the additional characters. It might be easy to say a player doesn’t need to own every fighter to be competitive, or every champion to be good at League, but it still requires some sort of recompense to get the tools needed to get there.

These systems create more systems, producing the haves and have-nots of esports.

These systems create more systems, producing the haves and have-nots of esports. To reach a certain level, the player has to be able to spend either obscene amounts of time or hundreds of dollars. They can haggle the price, but this fee is effectively unavoidable. And putting a price on being competitive doesn’t just stifle competition. It can turn away prospective fans.

Consider: my entrance into League of Legends was early on, somewhere between the release of Sona and Irelia in 2010. Because I was in college and had plenty of time to expend between classes, I had years to spend on League.. As the years went on, more responsibilities piled up. Jobs, coursework, and social time with friends around me rather than in-game all became more important than doing my daily ritual of League. I fell behind on champion releases, my rune pages were outdated and my choice was to either dive back in for hours on end just to feel caught up, or pay to get there.

Putting a price on being competitive can turn away prospective fans.

Free-to-play games leave behind those who can’t afford continuous investment. It’s a never-ending cycle of paying more, either monetarily or through pure playtime, to keep up with the esports Joneses. It makes sense, of course; ultimately, Riot, Blizzard and every other free-to-playF2P developer wants to maximize their profit. Artists, designers, balance teams and more all work to make these new characters interesting, to continue developing the game and keep it alive. But they have also done little to alleviate, or even address, the massive buy-in cost their games have accumulated over the years.

Bundles exist for League, if the player is willing to buy them up-front, but they do little to make a dent in the overall roster of playable champions. Games don’t necessarily need to go the Dota 2 route of having every character available for free, but even adjusted bundles, or, heck, a permanently free set of basic heroes would be a start. Limiting the effect of runes (or even addressing the importance of keeping them around) would alleviate new player concerns, instead of sending a two-weeks-in newbie into a panic looking for what the “correct” runes are to spend their hard-earned IP on.

Because, as-is, there’s a distinct and significant cost to be competitive in League of Legends. There’s a required amount of time and money just to get the tools needed to start the climb. Those who can’t afford it, or who don’t want to grind for months just to get to a point where they can focus on improvement over acquisition, are spurned by the systems in place. That’s not a good look for esports, and, in the long run, could deter many curious players from ever being more than a passerby.