‘Tis the season for Christmas music to blare from every direction. They come from speakers, carolers, and buskers. They are played in stores and putative public spaces. As a side effect of this sonorous onslaught, ostensibly cheerful songs become backing tracks to breakups and calls announcing the sickness of loved ones. Omnipresent holiday cheer, as social networks have previously learned, cannot coexist with sensitivity to personal context.

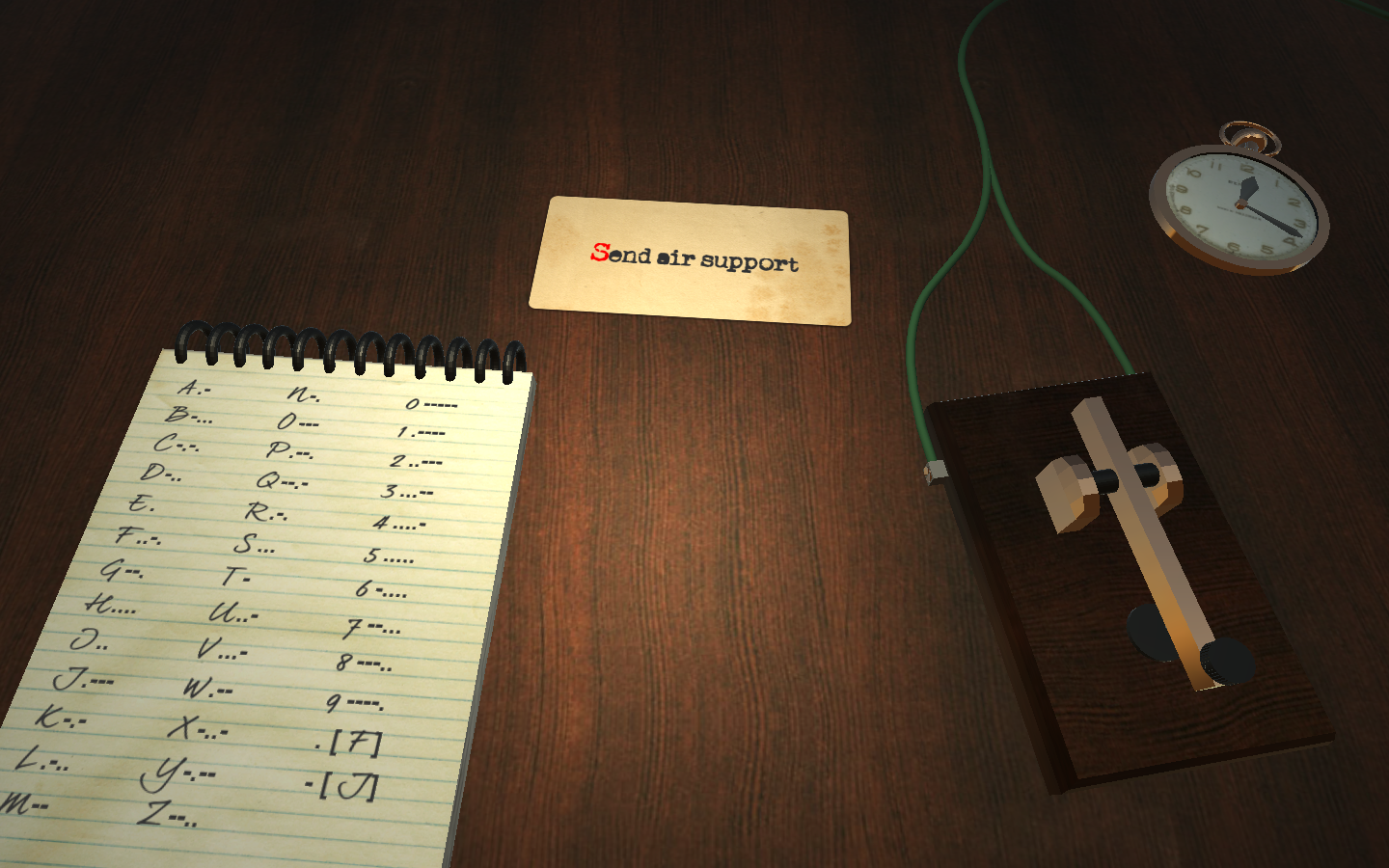

Relay, a game created by Jon Reid for the 34th Ludum Dare games jam, uses this incongruity to make a historical point. Set in December of 1914, the game juxtaposes a light, instrumental version of “Silent Night” with the sounds of the First World War, namely bombs dropping and telegraphs beeping away. You play as a telegraph operator, relaying messages from the front line. By necessity, the messages are short. By virtue of the nature of warfare—particularly in 1914, but also generally—they are unpleasant. The messages usually start with send: send air support, send food.

The messages in Relay, like the game’s background music, take on a musical quality. Unlike Alex Johansson’s Morse, which treated Morse code as a merely sequential series of long and short beats, Relay is concerned with the rhythm of these beats. The long and short notes that make up each letter must follow at very specific intervals; you can’t take a downbeat off while you find your bearings. Think of Relay as high-stakes Whiplash: are you rushing or are you dragging? At the same time, the game’s approach to Morse code is also exceedingly generous. An incorrect letter can be immediately repeated, leaving a jumble of long and short beeps in the middle of words for the person on the other end of the line. Relay is both a harsh musical challenge and much easier than the task it seeks to replicate.

This leaves the time to wring out all the gruesome meaning

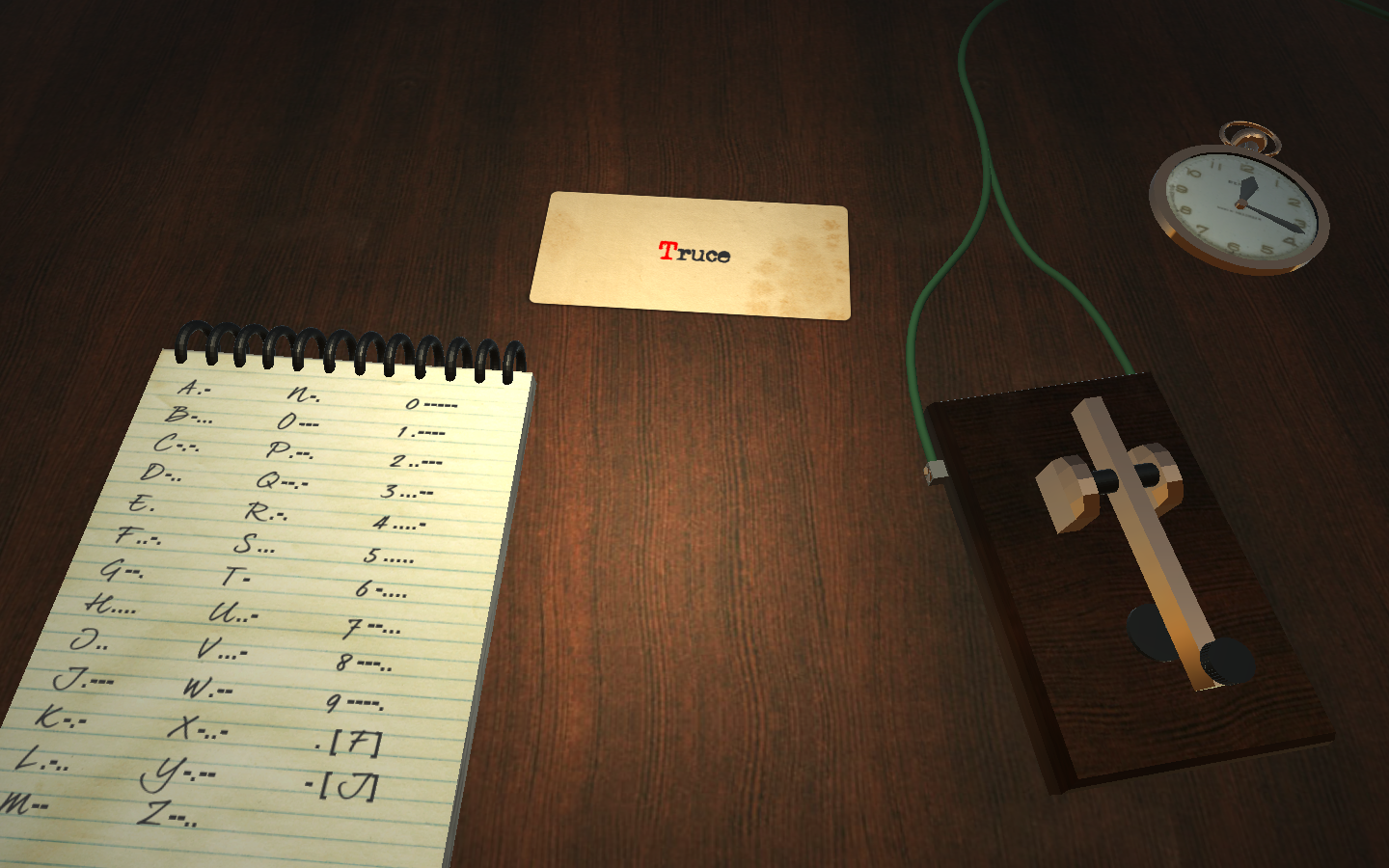

Relay’s use of “Silent Night” is not, however, a purely musical point. The game is interested in the precise historical context of December 1914 and, more specifically, the Christmas truce on the Western Front. Its messages and the delay casualty reports that come in between are an alternate way of describing the atrocities of trench warfare. Relay does not offer pictures or even particularly vivid descriptions of this hellscape, but uses Morse code to amplify the effect of its words. The prevailing thinking in higher education is that students who take notes by hand retain more material because they must slow their thinking and focus on every word. Relay’s Morse code transcription has a similar effect, forcing the player to slow down and agonize over every letter. This leaves the time to wring out all the gruesome meaning of phrases like “send food.”

The Christmas truce is the sort of feel-good historical moment that can be (and has been) transformed into a cheerful story. See, the incident seems to say, there is a fundamental goodness to these men. On one level, fair enough: men fighting in the trenches were not responsible for the course of the war. Yet to focus on the truce risks obscuring the general brutality of the war: it was very much the exception that proved the rule. That the story of the exception lives on (in videogames this isn’t limited to Relay, the truce also features in Verdun) is both understandable and worrying. The real lesson of war—and particularly this war—is brutality, and exceptions therefore need to be wielded with caution. Relay, with its terse wording and clashing audio clips, hints at this incongruity, but historiography has a way to go.