Thumper metes out violence like you’ve never seen before

In his long-time gig as resident bassist in Lightning Bolt, Brian Gibson is responsible for the cascading waves of unrelenting, screaming distorted bass that kick your chest almost as hard as they hit your eardrums. The amount of chaos created onstage by him and drummer Brian Chippendale is impressive; audience members have just two dudes to blame for their upcoming hearing loss.

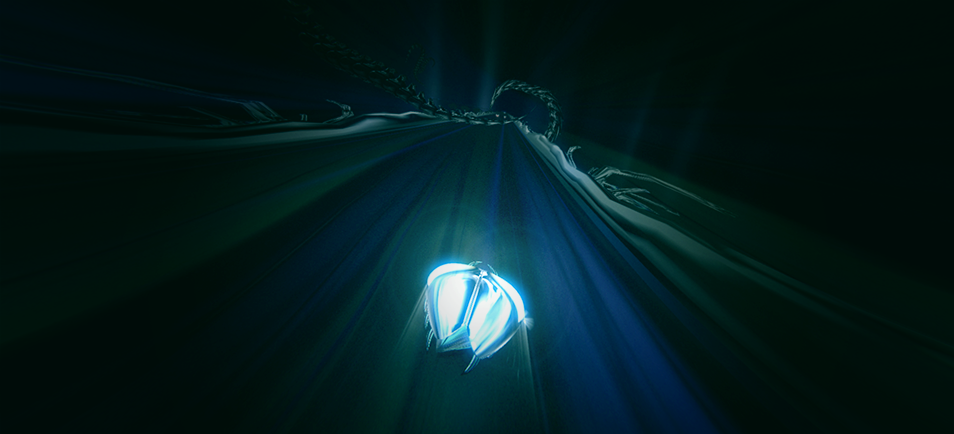

For the past 6 years, he’s also been a part of another chaos-inciting duo, developing videogames with Marc Flury under the banner of Drool. They’re putting the finishing touches on Thumper, which has the player piloting a flying, metallic space beetle careening down rails in an attempt to kill a giant maniacal floating skull named Crakhed, all set to foreboding, pounding drums and sub-bass tones.

Coinciding with the recent release of Lightning Bolt’s latest album, Fantasy Empire, Flury and Gibson have started to lift the veil of secrecy of their long-in-development title by showing it at development conferences like IndieCade East and GDC and dropping hints online that something is coming.

With the title of “Rhythm Violence” as its mission statement, the game’s latest trailer draws almost as many parallels to the widescreen, unsettling intro credits to Enter the Void as it does more standard rail-like racers like Audiosurf.

“It’s not violent in the classic definition of violence; there’s no blood or anybody really hurting each other, it’s just violent action,” Gibson told me. “Things physically banging into each other and getting destroyed. It’s kind of a funny thing that I feel like we have license to use the word violence, because it’s violent in ways I’m really proud of. It’s violent in that it’s shocking and has a physicality to it that is jarring and disruptive.”

Violent is accurate: the aforementioned beetle skitters unsteadily down a metallic luge-like trough, sparks flying as it screams down the track, accompanied by thunderous drums and dark synth blasts. The tremendous speed makes it difficult not to wince when you eventually slam into one of the countless barriers thrown up along the way, sparks and explosive elements flying everywhere. “Watching someone play it for the first time is actually really painful because they’re not good at it. The whole point is that you’re supposed to fail and die all the time,” says Flury.

While he doesn’t see a direct correlation between Lightning Bolt and Thumper, Gibson admits that, “you can connect the two projects, and I’m sure there are relationships that are immediate.”

“you’re supposed to fail and die all the time”

Considering how often the landscape of self-released games has been compared to punk rock—unpolished titles created by scrappy teams of artists/developers for their small but rabid audiences—it’s worth considering the fact that “punk” is such a far-encompassing umbrella; the Dead Kennedys and the Violent Femmes are “punk,” but it doesn’t take an expert to tell the difference.

A couple chords, shouted one-two-three-four countoffs and a snarl will only get you so far, though. Once you branch out from punk’s ragged edges and rudimentary grasp of technical proficiency in the music world, a broader palette of style, polish, goals and abstraction emerge. From Television’s heroic guitar virtuosity on “Marquee Moon” to The Minutemen’s docile pastoral ode to punk’s roots in “History Lesson, Pt. II,” expression of a counterculture needs to broaden its aim if it hopes to grow into a meaningful movement.

Punk’s not dead because it got too popular; punk’s dead because it became typecast.

Thumper’s ultra-glossy, 60 frames-per-second polish stands in stark contrast to the typical retro-styled, pixel-based platformers and Twine interactive narrative that’ve risen to the forefront of representing independent game development.

Flury compares Thumper’s aesthetic in the same way most would of the sonic barrage of a Lightning Bolt show. “What Thumper tries to do is bring the type of musical experiences that aren’t limited by what a pop song is or a dance song is,” he says. “It’s not about feeling good or having a 4-minute experience that is predictable and fun. The idea that music can make you feel lost or meditative or spaced out or afraid.”

The experimental noise rock Gibson is responsible for in Lightning Bolt dovetails slightly with the raucous carnage found in Thumper, but not due to the inherent violence implied by either project’s output: it’s in their simplicity. According to Brian, “When I get involved in projects I like to strip them down a lot, make them simpler. I guess I do like an ‘overwhelming’ quality, that it takes you somewhere else. It really transports you somewhere—I think that’s important to me, and I think Lightning Bolt does that.”

Even in an early state, the game already comes together as a cohesive whole, with precise, airtight controls, crushing difficulty and an equally hopeless and unforgiving soundtrack; Gibson is working to create “something that gives you a feeling of foreboding and terror and makes your heart race. Makes you feel engaged and gets your adrenaline going.” To get into that headspace, he cites Wendy Carlos’ despairing soundtrack for The Shining and the dissonant score for 2001: A Space Odyssey.

For now, the members of Drool continue to fine-tune Thumper into aggressive, hurtling perfection. They haven’t finalized what platform it’ll be released on. According to Flury, “officially, we don’t want to give a [release] date. We’ve been at this for 6 years, and we thought we’d be done 4 years ago.”

To learn more about Thumper or keep up with its development, check out Drool’s website.