Timruk explores the layers of historic violence beneath its beauty

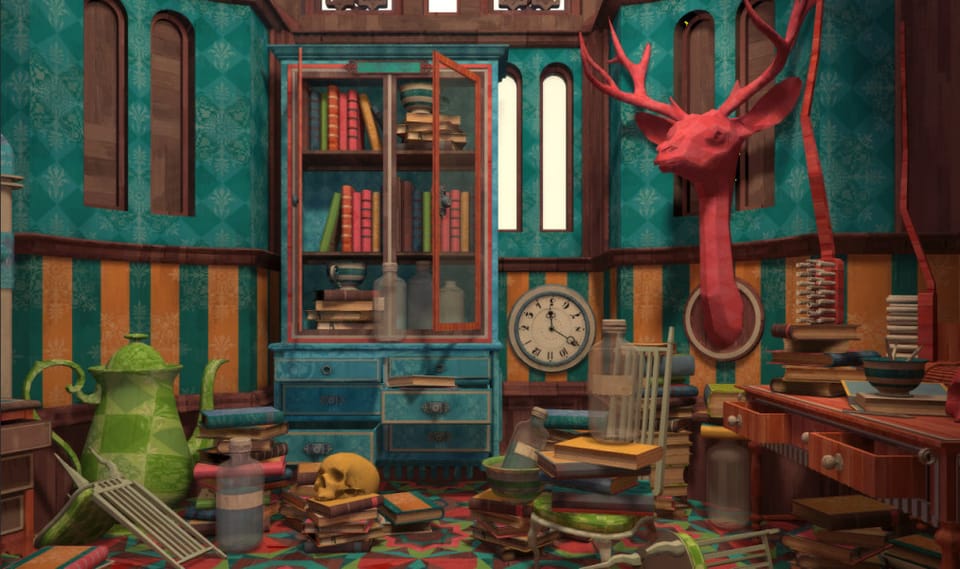

Pages contain bodies and blood both literal and metaphorical. Illustrations and text occupy a confined world of disarray, littered with skulls. Among this is the beauty of rain falling and of bright wallpaper colors. A world where your hands are not your own. This is a world of contrasts, the world of Timruk, the world of Somewhere.

Studio Oleomingus is simultaneously in the business of beauty and violence. Its latest game is called Timruk, which is a fragment of the larger upcoming videogame project Somewhere, following on from the studio’s previous off-shoot, Rituals. All these games have in common a thematic basis in colonial India but Timruk is a little different. It is concerned with a particular story that was, it should be clarified, entirely constructed by Studio Oleomingus.

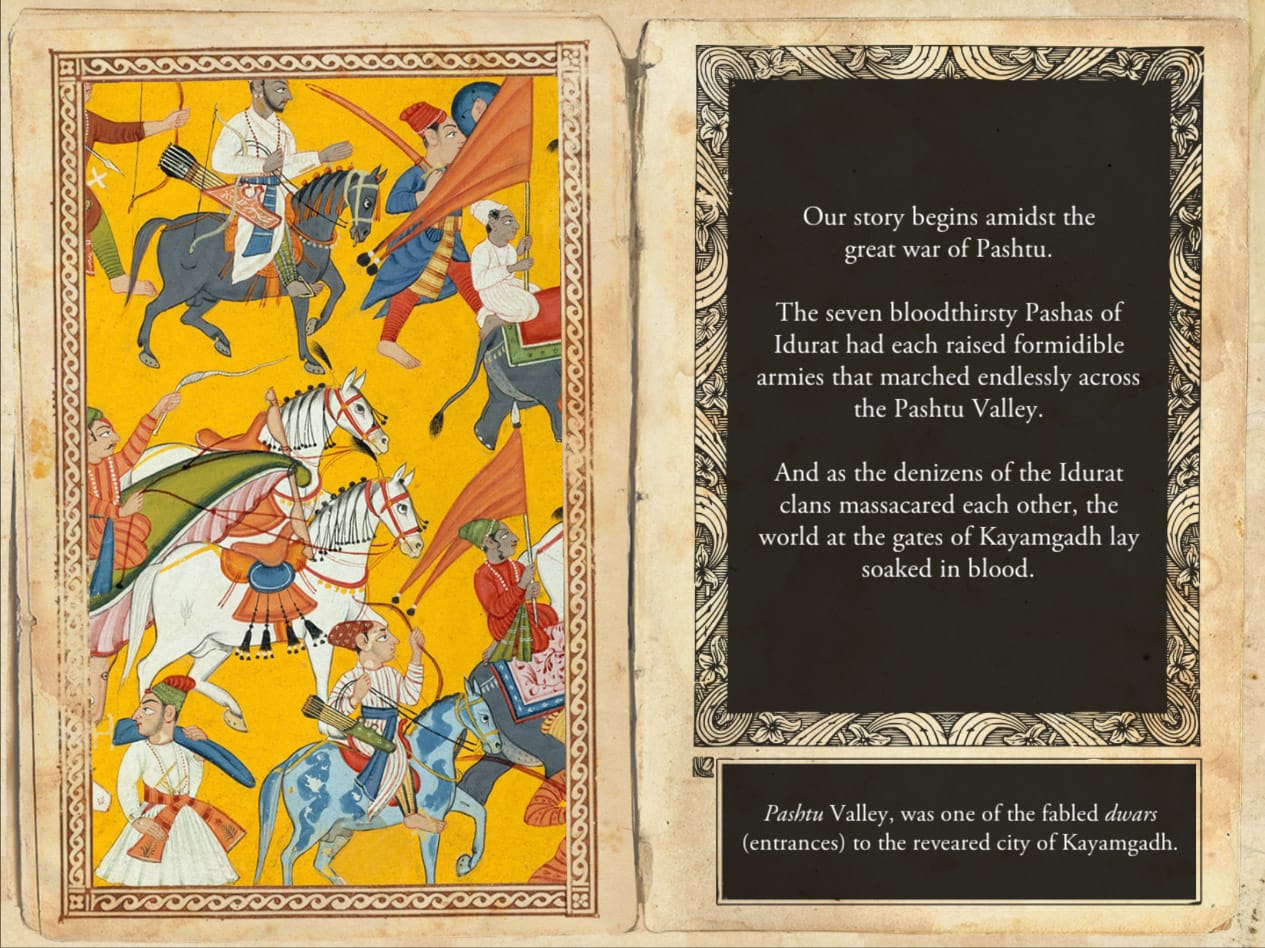

The game’s page tells us that this story originated as wall paintings which were translated to written form by a poet for the Rajah’s court in 1821. Later, this story became part of a larger folio, accompanied by miniature paintings scavenged from various Persian and Mongolian sources from the Maharajah’s library. Finally, the manuscript was translated by British historian, Prof. James P Fielding, being published in 1903. Timruk is said to be based on a copy of this historical story found in the archives of Calcutta State Library.

Studio Oleomingus is simultaneously in the business of beauty and violence

To honor its fictional source, Timruk is experienced as a storybook that presents you with ornate pages from the start. But the true experience of the game is being able to literally enter these pages and emerge in a courtyard. From there comes the narration, telling the story of two sons—both named Timruk—primarily through text and illustrations, which overlap with the rooms you find yourself in.

While it’s easy to read Timruk as being about about colonial forces in India it’s clear that Studio Oleomingus means to allude to far more complex power dynamics at play. Early on in the game, a telling of a battle is recounted, it mentioning that the book making workshop is walled up, as it’s feared the book maker’s need to depict the bloody battle will consume a precious and rare red ink. Here, the parallel between resources and bodies is subtly made—one must be sacrificed for the good of the other.

This theme is continued with ongoing reference to the beauty of book making and exclusionary collecting, with reference to all the rich resources that surround the craftsmen (golden leaf, Lac and Ocher paints, Mongolian ink pots etc.). These intricate trails of trade and war, as well as issues of class and luxury, have informed so much of human history. It reminds us that complex power dynamics stretch far beyond a world we often take to cleanly dividing into “pre/post-colonial,” as if we cannot imagine another metric. Perhaps we cannot, considering that our current context is so meaningfully enmeshed in that constructed divide in history. We are stuck.

As the pages turn in Timruk, you are transported from room to desolate room. Each contains its set of skulls. Death is everywhere. The contrast of Western-styled sitting rooms and open courtyards, and how they repeat in different forms, enhances the sense of limbo. Timruk is desperately beautiful from the rooms to the pages, but the quiet yet insistent layers of violence persist. It seems inescapable.

Timruk is free to download and play on Mac, Windows, and Linux. Be sure to follow Studio Oleomingus’s Tumblr for updates.