Kill Smaug, destroy the Death Star, and nail the game-winner in Titan Souls

Titan Souls takes a motif in film that’s so played out as to be empty, and uses it to create joy, triumph, and meaning in a context where we’ve come to expect the absence of all three. It’s an argument for what games can do that other media can’t because of their interactive and iterative natures.

I’m talking about the impossible shot. The hail mary. The curved bullet. You’ve seen it a hundred times, maybe most recently in Peter Jackson’s nine-hour exercise in self-congratulation, The Hobbit. There’s the dragon, Smaug, doing its Beowulf-y dragon duty, burninating the town. And, of course, there’s the older-but-not-too-old-to-fight warrior who knows Smaug’s one weakness. Dude parkours his way up to the top of the collapsing belltower, busts out the long-dormant crossbow built expressly for the purpose of shooting down this dragon, commits himself to save everyone or die trying, and then there ensues this suspenseful shoot-miss-shoot sequence where the warrior fires at Smaug’s one missing scale with a diminishingly full quiver. After a few airballs and glancing shots, he’s down to the last arrow. Then the warrior and the dragon share a meaningful look. Several ultimatums get issued here: “It’s you or me.” “It’s now or never.” “Come and get it.” “Smile you son-of-a—”

the warrior and the dragon share a meaningful look

And we can stop right here because you already knows what happens. What always happens, what must inevitably happen, what the genre of the epic blockbuster prevents from not happening. It wouldn’t have mattered if there had been hurricane force winds or Mini-Cooper-sized hail: that arrow would have found its mark. Smaug—a skyscraper-high dragon who survived for thousands of years because of the flamethrower in his throat and metallic hide—dies from an exceedingly well-placed toothpick. (And out of narrative necessity.)

This is corny. We accept the conceit as necessary for suspense—that the bomb must be defused with 0:01 still showing, that the universe-ending explosion must leave our hero unharmed—but this type of film generally only ever threatens to show us failure. The inevitability of the hero’s victory hollows out whatever suspense the film creates. After all, the arrow always finds its mark.

Videogames, on the other hand, surround us with failure. They make us touch it, live with it, hate it, embrace it. As Jesper Juul has argued, videogames are mostly failure, and that entails a different set of aesthetic criteria when we try to assess the meaning of success.

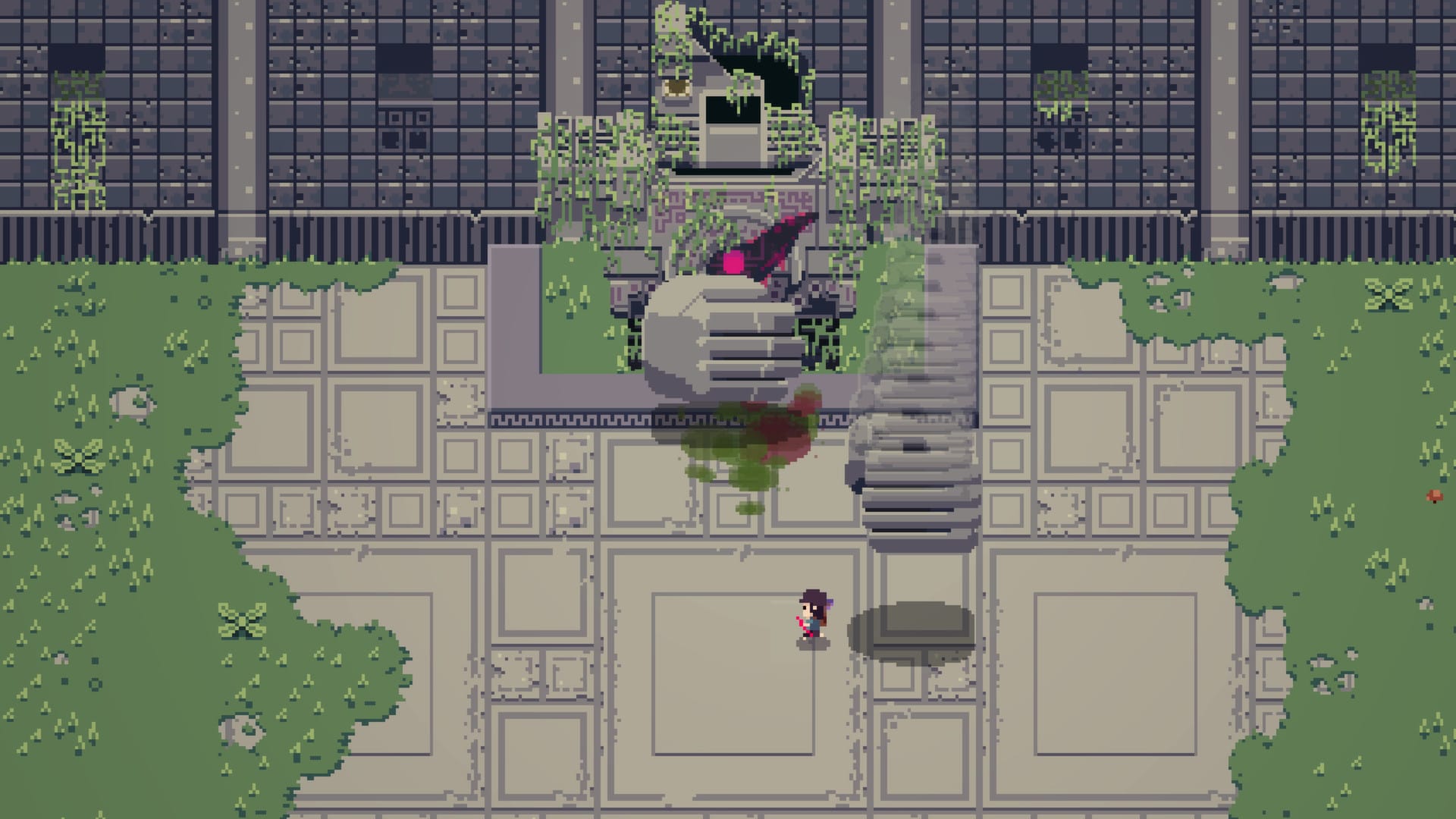

Titan Souls plays with the same variables described in the movie scenes above, but it recontextualizes them. The game tasks you with boss after boss, all set within a minimal milieu. You are a chosen hero, you encounter a gigantic monster with a single glowing weakness, and all you can do is try to guide your arrow home. But what Titan Souls resolutely refuses to offer is any certainty that the three should converge. Like other (unrelated) Souls-suffixed games, Titan Souls is wilfully and almost disrespectfully hard. I died on some titans twenty times before finding a suitable strategy, never mind actually making the shot.

But when you finally make that shot? When the winds are right and everything finally comes together thanks to your hard-headedness and a bit of dumb luck? The world stops. You can’t really put it into words. Jane McGonigal would call it “fiero.” Your arms go up over your head almost of their own accord. Your mouth opens out into this big, goofy, involuntary grin. You fucking did it.

Your mouth opens out into this big, goofy, involuntary grin

So what gives? How can Titan Souls make me feel like that when Hollywood’s version is akin to doing a couple shots of Nyquil? When Luke makes that stupidly unlikely shot with the proton torpedo that blows up the Death Star, we see joy and relief on Mark Hammill’s face and hear it rise in John Williams’s score. But, crucially, that experience is vicarious. We’re happy for the Rebels. Maybe we’re a little happier because of them. After all, Luke’s shot suggests that we might be able to do something in our own lives after the movie ends beyond what we expected of ourselves going in. But Titan Souls gives you the opportunity to feel that success first-hand, a joy forged in the crucible of failure.