The Tomorrow Children would fail a history exam

The Cold War refuses to separate itself from the West’s understanding of the Soviet Union. Decades of apocalyptic rivalry have painted its immensely diverse citizenry as, by turns, dispassionate murderers or buffoonish caricatures. On one hand is Stalin, casually signing the paperwork that ordered the mass killings and deportations of the Great Purge; on the other are the workers and soldiers of the Union, imagined as simple-minded enough to follow the suicidal directives of their leaders. One of the most staggeringly unusual empires in human history has, in popular consciousness, been watered down to a collection of non-thinking laborers, power-hungry politicians, and the looming violence of the immense anthro-mechanical structure their combination created.

In truth, the Soviet Union was an amorphous and complex phenomenon. Existing for nearly the entirety of the 20th century, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was not a static political entity. Though based in Russia, it was multinational; while it was forged in Bolshevik implementation of Marxist thought, its politics changed with time. The Russian Revolution of 1917 and formal solidification of power in 1922 offered a utopian replacement for an increasingly stifling autocracy. Gorbachev’s introduction of perestroika and glasnost offered concessions to the perversions of Stalinist rule and an end to the Cold War. From its beginnings to the time of its late 1991 dissolution, the USSR was always in the process of transforming both itself and its citizens.

Its aesthetic is remarkably unsubtle

Videogames have never tried particularly hard to portray the complexity of Soviet history. The best attempts to date tackle either the specifics of its soul-crushing bureaucracy (Lucas Pope’s Papers, Please) or generalized tales of cultural identity in an Eastern Europe still reeling from decades of Communist rule (4A Games’s Metro series).

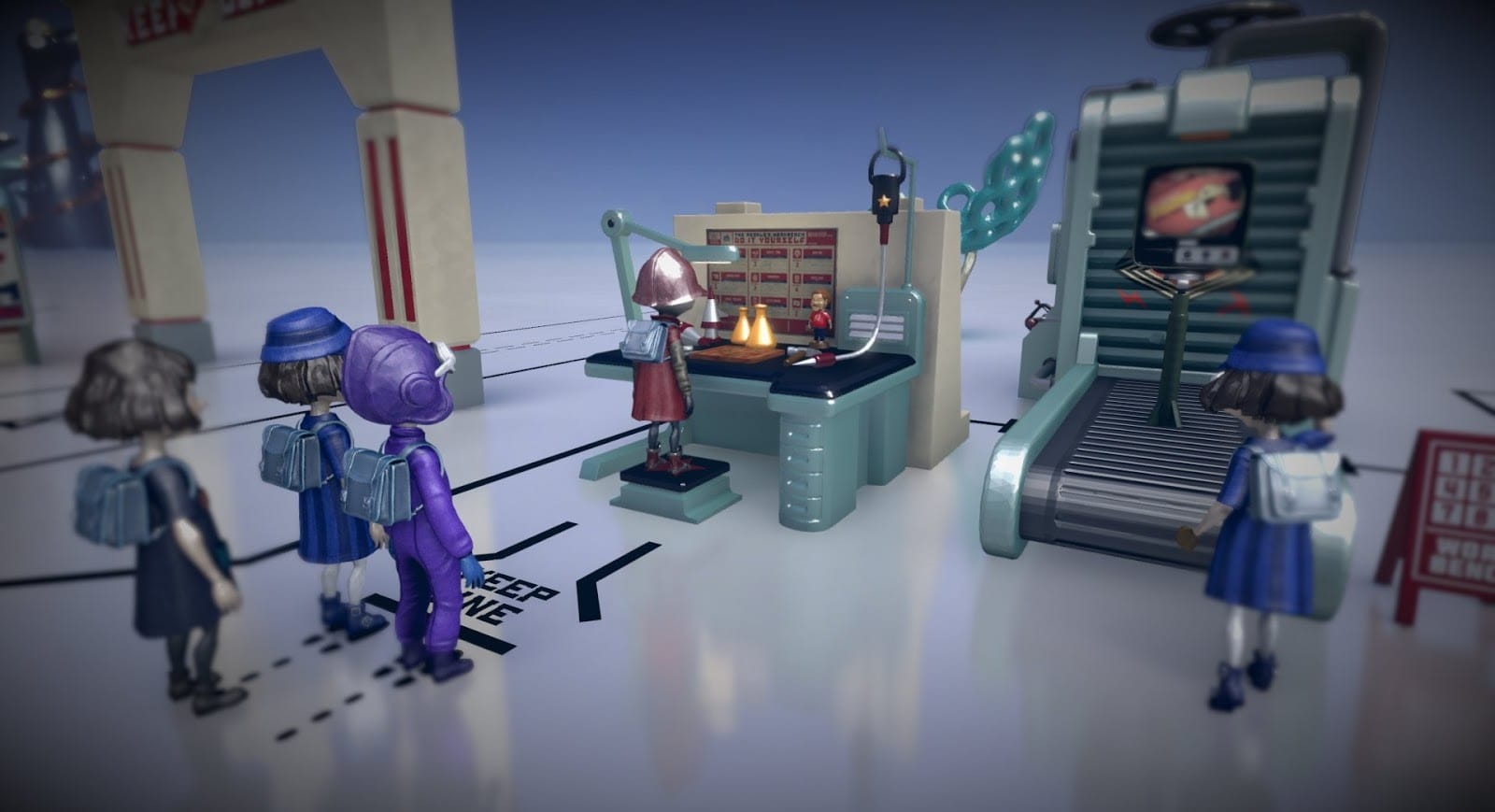

The Tomorrow Children is both broader and more directed than what’s come before. The player is a semi-human “projection clone” who lives in a sprawling wasteland created after a failed 1960s experiment. The idea was to “meld all human minds into one global consciousness,” but what happened was the annihilation of the world. Explicitly science fiction in premise, then, the game’s point of reference is an imagined, static vision of the USSR through the lens of a capitalist propagandist. Its aesthetic is remarkably unsubtle. The player character is a living doll—apple cheeks and bright blue Bambi eyes; a Slavic stereotype. Her various outfits are culled from the imagery of Soviet cosmonauts, revolutionary soldiers, and threadbare intellectuals. The non-playable characters are similarly cartoonish, herds of ageless peasants watering plants with slack, bovine expressions while stiff-backed policemen patrol the streets, monitoring their territory and quick to issue ominous threats urging the player to get back to work.

The towns in which the player resides quickly become filled with giant propaganda posters in faux-Cyrillic text, blocky machines with ugly, intricate inner workings, and space-age hover cars. Signs say “Public Enemy” next to a picture of a dollar sign; fake newspapers are emblazoned with “Our Great Motherland”; red and yellow abound on flags and monuments—the game does everything short of emblazoning the hammer and sickle on its surfaces (itself, like the characters’ pseudo-Russian babble, a strange, maybe cautious point of departure among so many precise references).

For a little while, it’s possible to think The Tomorrow Children’s look is in service to a satire. The goal, an endlessly repeating five-year plan that resets upon completion, is to build up a given town’s population and increase its productivity alongside other real players. Coming to grips with the process for gathering resources, buying new equipment, and upgrading the town’s infrastructure is a maze of new terminology that mimics the bureaucratic labyrinth of Soviet officialdom. Blatantly unfriendly design choices—a travel system that requires long waits for slow-moving buses; tools that break after too-few uses; having to wait in line to access any public building—show that The Tomorrow Children is willing to prioritize thematic intent over convenience.

This thread continues in the relationship between real-world capital and the game itself. Notably, The Tomorrow Children is “free to play,” which is in quotations because, of course, there’s always a catch. As in other games of its type, anyone can download The Tomorrow Children, but those willing to spend a bit of their actual money can buy an advantage over their peers. The game’s real-money currency is earned more slowly than the ration coupons meted out regularly, and can be used to bypass the requisite (agonizing) sliding block puzzles that must be solved before crafting any of the town’s shared vehicles, armaments, and infrastructure. Cheekily, those who purchase access to the game before its full, free release automatically earn “bourgeois” status, too, which allows them to use technology that “proletarian” players must work toward.

never quite manages to form any kind of statement to justify itself

The most charitable reading is that these systems are commentary. Everyone gets basic entry to the game, but spending extra allows a player to overcome obstacles and further their place in the virtual society. But, like the Red Scare visual design, the player has to be pretty forgiving to imagine that The Tomorrow Children is attempting anything other than a shallow recreation.

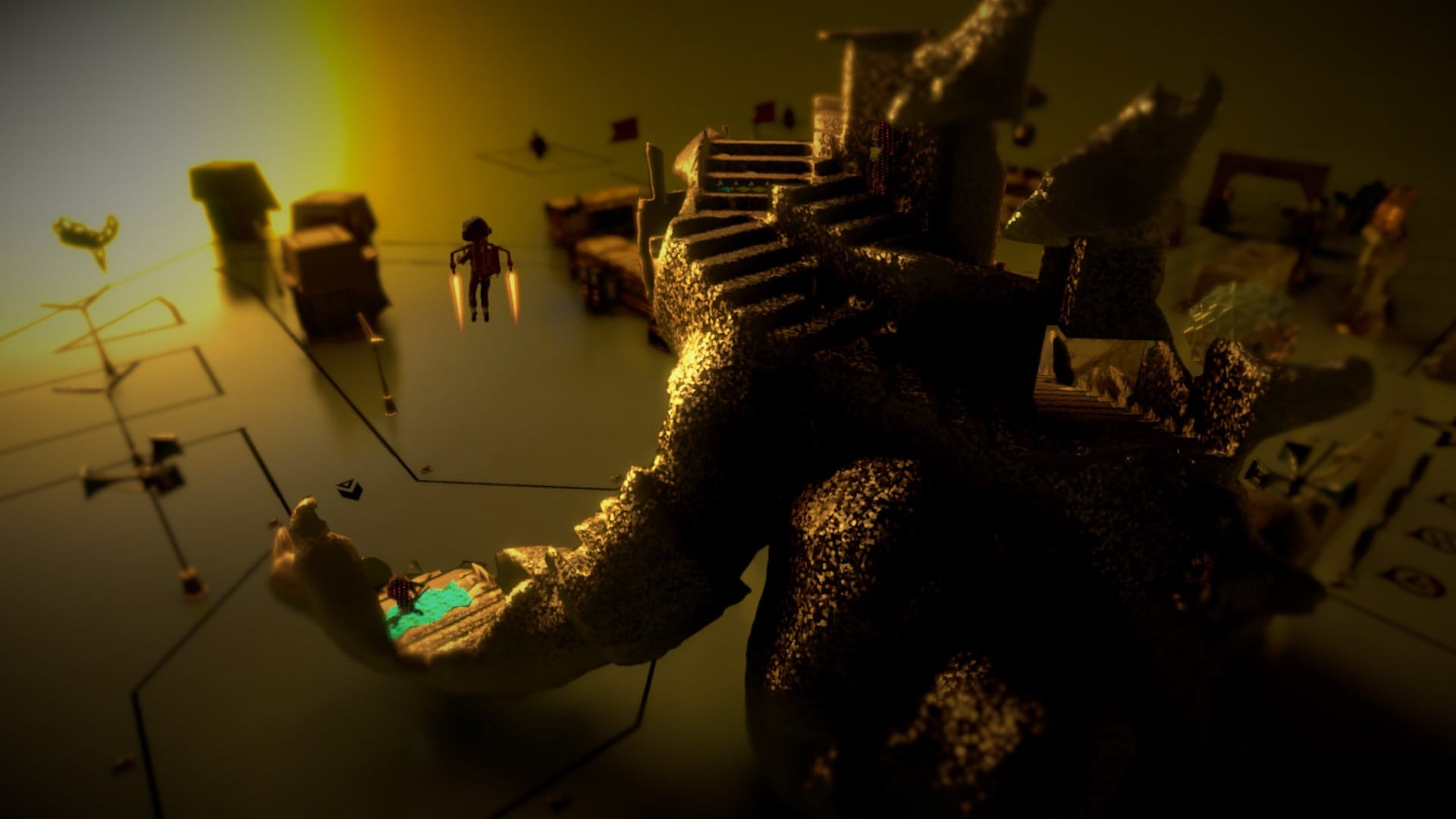

The only real subtle touch—as subtle as skyscraper-sized metaphors can be—is the presence of giant monsters that lumber around the endless mist surrounding the player’s town. When they turn their attention to the group settlement, their enormous, Godzilla-like bodies offer both threat and resource. The monsters, always present but often indifferent, eventually decide to stomp through town, reducing public works and housing to flaming, useless husks. Once shot down with emplaced guns, their bodies become temporary mines, ready to be pick-axed apart into valuable resources. Between the safety of the player’s home and the islands of monster corpses that hold important wood, coal, and metal, the world is a swirling white void that damages and eventually kills with brief exposure.

Alone among the context-free pastiche of the rest of the game, The Tomorrow Children makes reference to the Soviet Union’s political isolation with these monsters—its view of the rest of the world as both a constant threat to its survival but an opportunity, too, for expansion. Working with a small army of fellow players to bring down one of the beasts, mining its guts with an ad-hoc assembly line of miners and cargo haulers, is the closest the game comes to capturing something more than superficial. It portrays collectivism as more than a purely negative system. Elsewhere, having to share collected resources means some jerk might build an unnecessary structure or fail to pull their weight generating energy for the town. Still, even as it grasps toward making its depiction of Soviet life felt rather than simply reproduced, The Tomorrow Children never quite manages to form any kind of statement to justify itself.

Videogames are mostly bad at portraying history, understanding well how to capture what a period of time might have looked or sounded like while failing to offer a reason for the player to care that it happened at all. Too often, the past is used as exotic set dressing for stories that could very well take place at any time at all. In a bad entry to Call of Duty or Assassin’s Creed, the audience is presented with a sort of time porridge in which the exact same gunfights, chase scenes, and story arcs they might enjoy in a sci-fi thriller or current-day action game are grafted onto the battlefields of Second World War France or Victorian-era England, with no regard for the culture and sociology of their chosen era.

The Tomorrow Children is yet another game in this mold, eager to replicate an era without anything in particular to say about what it meant. It teaches very little other than that the Soviet Union was a place where communal governance was both a good and bad thing—that everyday tasks were more difficult and that propaganda masked the kind of hypocrisy where money and status still mattered an awful lot despite official egalitarianism. This is not enlightening and the experience of engaging with The Tomorrow Children’s abstracted recreation of these phenomena does not impart any greater lesson. In the end, it’s kitsch. It’s a Soviet-themed Lego set that renders a monumental socio-political phenomenon into little else but a toy. And an exceptionally boring one at that. This would all be harmless enough if the aesthetic it borrowed wasn’t one of paranoid violence and a complex unraveling of a utopian dream for all humanity, but, that’s what the USSR was. The waxen, dull-eyed and stiff-limbed toys that fill The Tomorrow Children are not representatives of the world they’re drawn from. They’re the outward face of the kind of malign simplification that characterized the Cold War.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.