Touch & Go: Exploring Alternative Controllers

It’s Sunday afternoon. The exhibit space is in a frenzy. Robin Baumgarten, a London-based game maker, is in Toronto for an exhibit featuring his game, Line Wobbler. As we pass by workers busily preparing the exhibit space, Baumgarten shows me the deceivingly simple-looking controller at the core of his game: a door stopper spring. The inspiration for this unusual controller is a video of a cat playing with a door stopper, using its paw to flick it to and fro. As with that cat, the controller proves to be what fascinates the many exhibit and festival goers wherever the game is shown.

Baumgarten made Line Wobbler back in 2014 alongside Matthias Maschek. It’s become a shining example of the growing interest in games made with custom controllers. These games often combine and re-combine the digital and the physical—creating new forms of playful experiences by mining some of our most mundane habits (such as stacking things or even kissing) to remaking and reusing objects (such as telephone switchboards to quilting machines).

Minimalism and custom-made controllers harken back to the early days of games

Since 2014, the Game Developer’s Conference has recognized this emerging category in games with its own special exhibit called alt.ctrl.GDC, a space dedicated specifically to games with alternative controllers that “challenge traditional forms of input.” Now in its third year, submissions have more than doubled since the exhibit’s creation. This year’s edition features 20 games chosen from a pool of over 140 games submitted. Over at IndieCade, a festival dedicated to independent games, a similar boon is afoot—with submissions of games with nontraditional controllers doubling in the span of one year.

Last year’s alt.ctrl.GDC featured Line Wobbler. “[It] was as much a decorative lighting piece as it was an exercise in minimalism,” says John Polson, co-organizer of alt.ctrl.GDC. Indeed, minimalism is at the core of Line Wobbler, it being played with no more than the door stopper with the player’s actions displayed on a long strip of LED lights. A 1D dungeon crawler, the player wobbles and bends the controller to move her light avatar along the strip— fending off red-tinged enemies and other lighted obstacles. The lighting effects are reminiscent of the moving lights from glow sticks while the explosion of multi-colored lights (when you die) feel like the burst of feedback you get from a casino.

Line Wobbler via Robin Baumgarten

This minimalism and the game’s custom-made controller harkens back to the early days of games. “Alternative controllers, as I consider them, were a staple in our industry since its inception. When you look at Computer Space (1971), Pong (1972), Asteroids (1979), and countless others, their controllers were fascinatingly unique as designers were tackling how we interact with games that now existed in video form,” says Polson.

Arcade games also often experimented with controllers. Mike Lazer-Walker, a Cambridge-based game maker known for Hello Operator (a game made with a vintage telephone switchboard), fondly remembers Konami’s rhythm games like Dance Dance Revolution (1998) and Beatmania (1997) as some of his first encounters with alternative controllers. “I remember being mesmerized by being able to play games by some means other than pressing buttons,” recounts Lazer-Walker.

ROTATOЯ via Robin Baumgarten

Alternative controllers, then, aren’t a new thing. What was once considered a nontraditional or alternative controller can gradually become mainstream and traditional. “Over time, arcade and console controllers generally normalized, but that didn’t stop the inventors from inventing, at any level,” says Polson. This continuous invention led to controllers like the much-maligned Power Glove, released for the NES in 1989, as well as more recent ones like the Oculus Rift.

What has changed over the years is the growing experimentation and production of these controllers by smaller-sized teams. Game makers like Baumgarten and Lazer-Walker function as software creators but also as platform creators. They craft the world of their games but also the very container, a physical object, that allows players to enter these worlds. “Being able to use a controller as a theatrical prop, either to help immerse you in another world or just to help you look like a fool in front of your friends, is incredibly powerful,” explains Lazer-Walker.

These controllers are often one-of-a-kind, never intended to be mass-produced

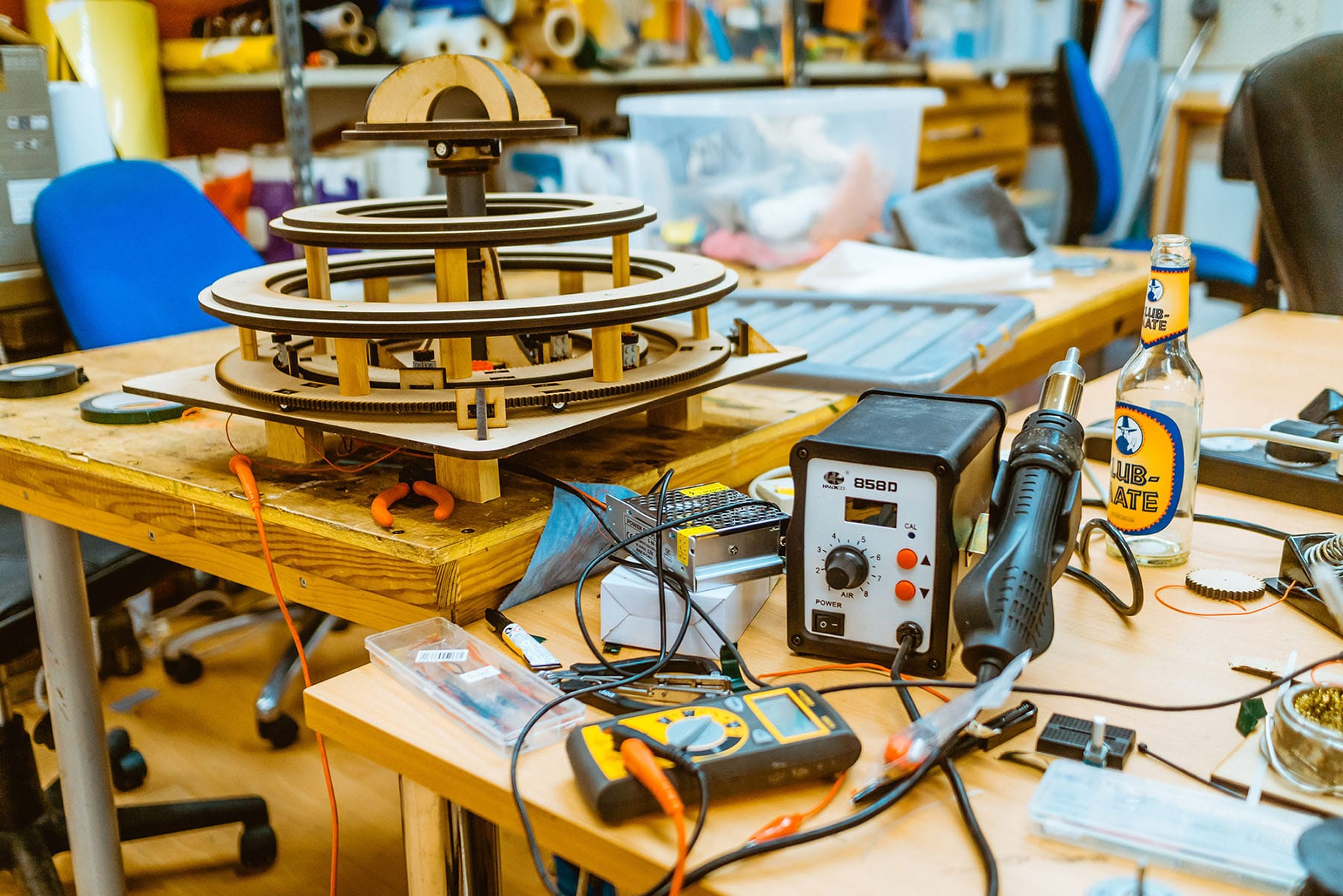

Making these custom controllers, however, is often accidental. For Sagan Yee, a Toronto-based game maker known for Punk Prism Power (2015)—a game with custom-made weapon controllers—her games tend to include alternative controllers mainly because her friends are part of the larger maker community with access to makerspaces. These places let her and others hack, craft, and tinker using fabrication tools like 3D printers and laser cutters among others. Baumgarten had similar influences: “[My sister] studied industrial design and was actually into these things earlier than me. She introduced me to Arduino. She wasn’t good at programming at first so we combined our efforts — I’d help her with programming and she would do the physical side.”

Like Yee, Baumgarten and other game makers are pulled into experimenting with physical objects and hardware by peers who aren’t necessarily entrenched in the videogame world or focused on screen-based works. What results is often a mix of eclectic projects (from Magical Girl weapons to steering-wheel inspired controllers). Reminiscent of the Art and Crafts movement of the late 1800s, with its emphasis on custom-crafted objects, the maker movement springing up from communities like makerspaces is helping influence game makers to look beyond the digital and into the physical world of custom crafted objects.

Line Wobbler via Robin Baumgarten

Moving into the physical world does not come without its challenges. For a smaller-sized team like the Mahou Shoujammers (the six-person team behind Punk Prism Power), mass producing those Magical Girl weapons would be time-consuming and expensive. Unlike digital games where people can access or share the games through online stores like Steam or itch.io, there is no easy and scalable way to share games with custom-made controllers. More than that, these controllers are often one-of-a-kind, never intended to be mass-produced. But teams like Sensible Object (the group behind the tower stacking game, Fabulous Beast) are paving the way through their experiences in mass producing their own custom-controlled game. It gives us hope that these games and their controllers won’t just be limited to appearances at festivals and conferences.

As these games steer away from traditional controllers (and even screens), some wonder if they are a separate category of games altogether. Celia Pearce, Festival Chair at IndieCade, doesn’t think so: “We are about to enter into a whole new era where the boundaries between games, toys, computers, and board games will be further blurred.”

A week after I chatted with Baumgarten, the exhibit featuring Line Wobbler finally opens. As in the game’s previous showings, curiosity pulls in a crowd. Baumgarten later captures this scene, a typical one for the game, of kids huddled around the game with eyes transfixed to the moving light above them. Speaking of Line Wobbler, Baumgarten echoes IndieCade’s Pearce: “Some people call it a toy. Some people call it a game. But what are games? I don’t really mind what people call it. I’m just happy they’re playing and enjoying it.”

Line Wobbler is on display from March 5 – April 24 at the TIFF digiPlaySpace. ROTATOЯ and Hello Operator will also be featured during this year’s alt.ctrl.GDC from March 14 – 18.

///

Header image: Line Wobbler via Robin Baumgarten