Turning down the volume on Volume

I look left. Two guards patrolling back and forth. To my right, one planted against a wall staring parallel. Can’t go that way but I need to, gotta grab those gems. Uh-oh: dogs. They’ll smell me if I’m not careful. Over there. A bugle, makes a loud noise. I’ll throw that to send one of them over. Alright, now gotta hide, quick. Gotta do this right, or else—he spotted me. Hide, quick. Lost ‘em, that bought me some time. Damn, spotted again. Hide—dead. It’s alright, I passed that checkpoint. Okay, again.

///

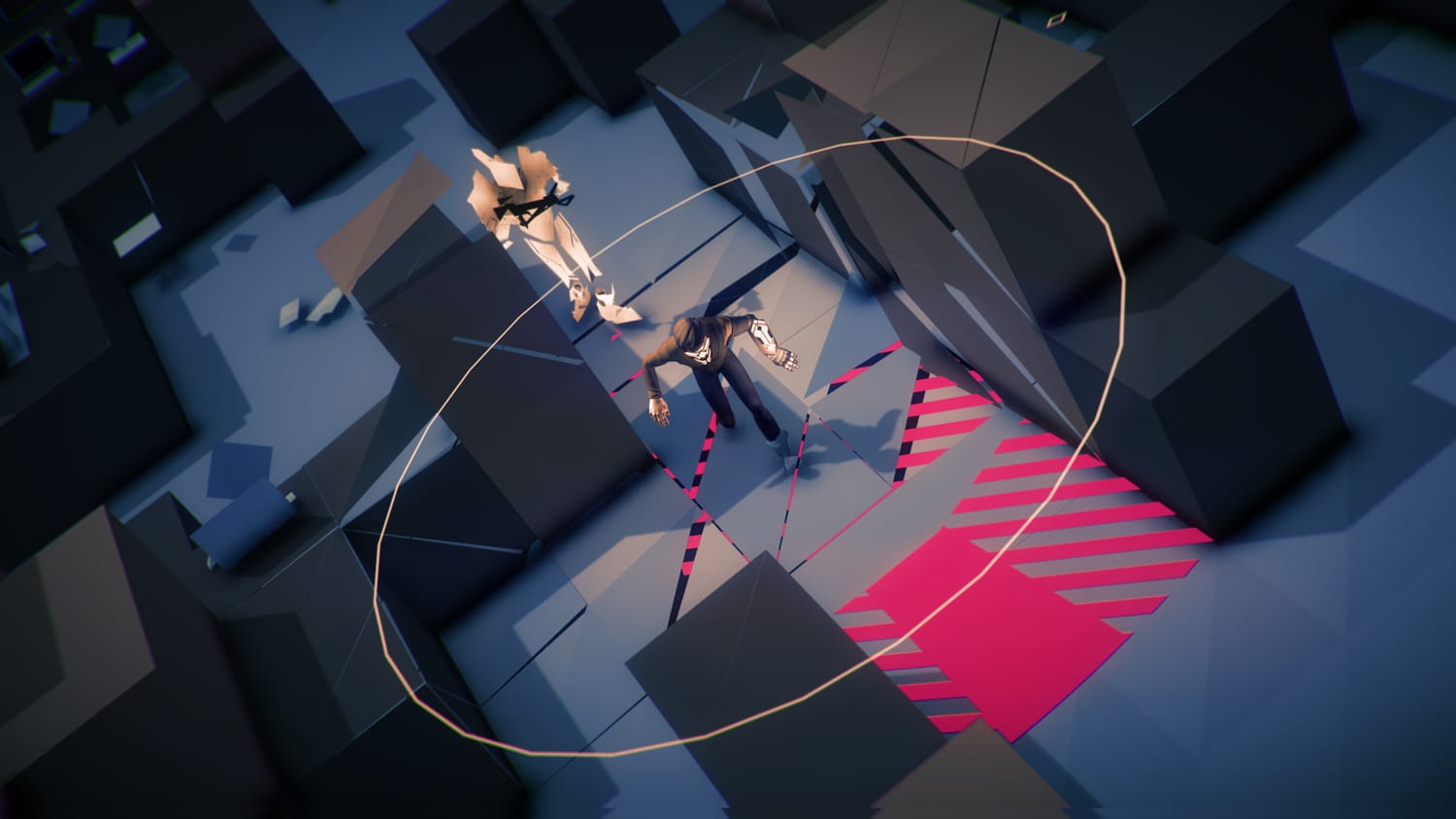

As with his previous game, the twee platformer Thomas Was Alone, designer Mike Bithell demonstrates a pension in Volume for pulling from videogame’s past. In both games, he distills aesthetics and mechanics to their core in order to directly poke and prod upon our senses. This time he’s tackled espionage, emulating the original Metal Gear Solid’s get-in-get-out-and-don’t-get-caught approach, but without the overwhelming array of tools or the overburdened narrative. As in that game, we watch from a bird’s eye view as the peppy but existential protagonist Locksley sneaks around cuboids. Nameless VR guards known as Volumes shoot us and send us back to the last checkpoint if we fail to find a suitable hiding spot in time. We grab gems, bank them at one of several reusable checkpoints so as to not lose progress, rinse, repeat.

But despite this, Volume is refreshing—sometimes calming, sometimes challenging, sometimes frenetic. It’s the Ocean’s Twelve-style dance with alarm-triggering lasers, where every move however so slight counts. The euphoria upon cooking up a solution to a difficult problem and executing on it. Endorphins flow and synapses fire. The game’s Tron-inspired visuals and Vangelis-like soundtrack both pulse with a tension that the game’s fundamental actions back up. But mostly what works is the sneering, “what’s yours is mine now” joy of the heist. The simple pleasures.

Volume is refreshing—sometimes calming, sometimes frenetic

In one of its hundred levels, six or so guards patrol back and forth in their own alleys. Their patrol is perfectly timed so that they all meet up in the center circle. It’s mesmerizing to watch, like a gif of some graphical simulation of an algorithm. I sit and watch their mathematically rhythmic movements from safety for awhile, but it’s soon clear that there’s no path I can currently take to avoid detection. Furthermore, there are a bunch of gems to collect in this area, so I’ll have to exhaustively cover the grounds in order to open the exit. Luckily, my foes are pretty stupid: when provoked, they’ll come looking for me and return to their previous pattern, but if timed well will fail to match the engineered cadence of the group. Blowing a faint whistle, I can simply attract their attention to temporarily clear a way, grab some gems, and repeat, until I’ve done all I need to, and hightail it out of the vicinities.

These are simple, repetitive pleasures, and the game lays claim to them without shame. It does raise some questions, though, about the onset of VR, and I can’t help but imagine this future might be less glamorous in reality than in our fictions. Locksley runs around an empty room with his VR headset equipped, stealing from the rich to do good, but having a blast doing it. He is there to play, to have fun. As a set of rules, Volume may just be a cold metaphor for the videogame power fantasy. We are told again and again of our awesomeness, that what we are doing is worth spending our time on, that mistakes are just a light checkpoint away from being rectified. We feel as if in some way one with what exists beyond the screen, as if it is some tangible place we can go to escape.

Bithell seems to agree; the heavy narrative throughout Volume certainly implies as much. While playing, we’re often privy to a distinctly British dialogue exchange between Locksley and his witty artificial intelligence partner Alan, poking fun at their dystopian society and each other. Alan too is a Volume, a “race” of AI so prominent and convincing they’re seen as a threat to humankind, like Blade Runner’s are-they-aren’t-they replicants. Alan is human enough that Locksley befriends him, but also his robotic nature means that he must be a friend, he must obey, even if he desires to interject.

In a handful of its optional lore logs, Volume does employ its AI to tepidly pose questions on the ethical and moral dilemmas of segregation, but in the end chooses to bank on its man-against-the-world narrative. This is a power fantasy the likes of which we’ve all seen before, and will continue to indulge in, likely because it’s good. And that’s okay. I accept that, or rather, succumb to it. But other texts of email exchanges and newspaper clippings try hard and often to persuade me of the obvious: that governments are evil and should be policed. Optional though they are, these logs most detrimentally commit the cardinal sin of bringing the blood-pumping stealth sexiness to a whiplash-inducing halt. This gets at the core appeal here: Volume’s strengths are primal but simple, at times feeling like a Crossy Road-style time-passer with a cyberpunk sheen. It tries but ultimately doesn’t say much of modern society or governments beyond the elementary. Indeed, it is the modern videogame incarnate, warts and all.