Twinescapes, or The Rise of Spatial Hypertext

At least 100 pages of four novels. At least 20 pages of maybe half a dozen others. Not one book finished, not even in rough draft.

These are the vital statistics of my long war with fiction. For most of my life now it’s been my fondest wish to write and to publish a novel. Sometimes I’ve wanted to author a book of the Great-American-sort, other times my ambitions have been more humble, or more genre-bound. Sometimes my drafts have been muddy slogs through self doubt, other times they came as if poured from a vase by a woman in a toga. But every time I ended up feeling like something was missing, like I was doing something incorrectable.

My biggest compositional struggle has been over the right ways to move characters through an imaginary space. When I started, everything I wrote felt too static, with the characters all sitting in chairs or standing statuesque in their rooms. But even after realizing this defect, I never really knew how to proceed. Do I use the progression of details to give the illusion of a character’s thoughts as he walks down a street? Do I describe her walking pace, or the nervous way she shifts from one part of the room to another? Do I do as Umberto Eco in composing The Name of the Rose (1980), when he drew a scale map of his medieval Italian monastery so that he could know the number of paces between the scriptorium and the stables? I still haven’t found an answer that satisfies me.

So it’s with personal interest that I’ve noted a new fictional form emerging within the world of games. Twine-based interactive fiction, text stories made of clickable links and branching pathways, straddle the very threshold between game and literature. And I think interactive fiction, in the hands of certain writers and designers, also represents a new formal association between space and text.

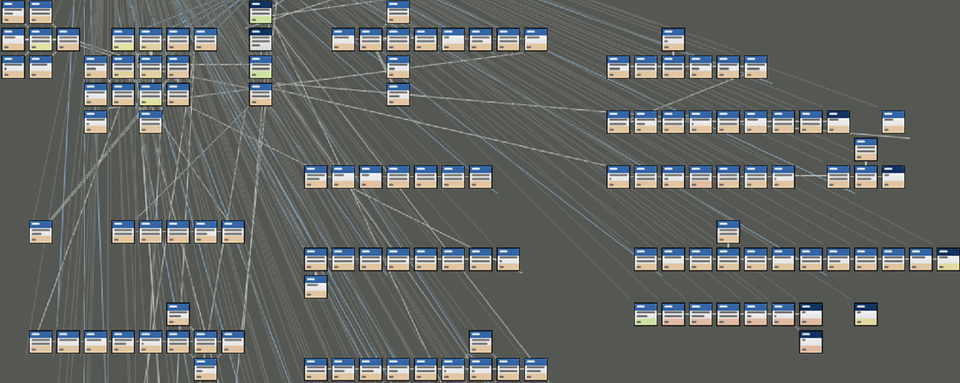

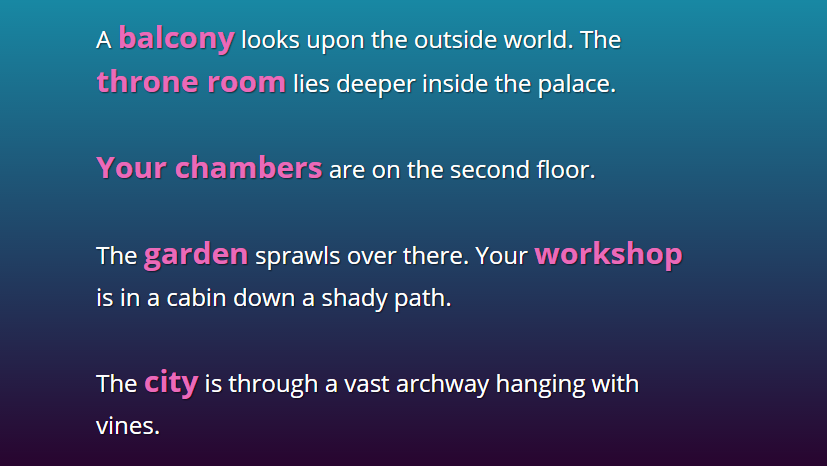

My inroads into Twine fiction was Porpentine Charity Heartscape’s With Those We Love Alive (2014). Told in the second person, the game thrusts the player into the role of an Artificer in service to an insectile Empress. Porpentine’s is a world where “Angel corpses rot in the sun” near a “dream distillery”, all of it “stained with smog and acid rain.” Her images are at once precise and yet broad enough to imply a whole deeper world. But this world is also given a feeling of physical depth, of spatialization, by the structure of Porpentine’s game/story. In a given passage certain words will be colored links, as in the following (with italics standing in for colors): “The garden stands over there. Your workshop is in a cabin down the path.” Clicking these links brings you to a description of the garden or of the workshop, respectively, and each of these descriptions might have links inside them as well.

This act and activity of clicking links serves as a metonymy for active motion between one place and another. In a traditional story the movement would be described on the page: “You walk from the palace courtyard to the garden.” But in Porpentine’s work, and the work of other interactive fiction writers, that fussy movement of characters like chess pawns is elided. What reigns instead is detail and an imagination of space.

this already spatial story is reaching out to haunt the physical world

What’s more, With Those We Love Alive is not a sort of “choose your own adventure story” made of unrecoverable choices. If you go from the courtyard to the temple you can go back to the courtyard and on, to the lake. These settings may or may not change from one appearance to the next, but even the repetition helps ground the game in a sense of spatial reality. You move around inside the story rather than tracking an inexorable march of words rightwards and down the page.

This desire for a spatialization of the text extends to one of the most often remarked upon features of With Those We Love Alive. The game asks you to draw symbols upon your body that represent abstractions like new beginnings and separation. In another place, the game asks that you—the player—hold your breath for a length of time. These effect are powerful, as if this already spatial story is reaching out to haunt the physical world.

If I were to generalize massively, I would say that the relationship between a traditional paginated novel and Porpentine’s work is that the former is about the passage of time while the latter is about movement through space. Which is not to claim that a novel can’t provide a sensation of dimension, or that With Those We Love Alive doesn’t have an affecting narrative. But I do want to point to the unique strengths of writing and design like Porpentine’s and how these strengths are different from the fiction that came before it.

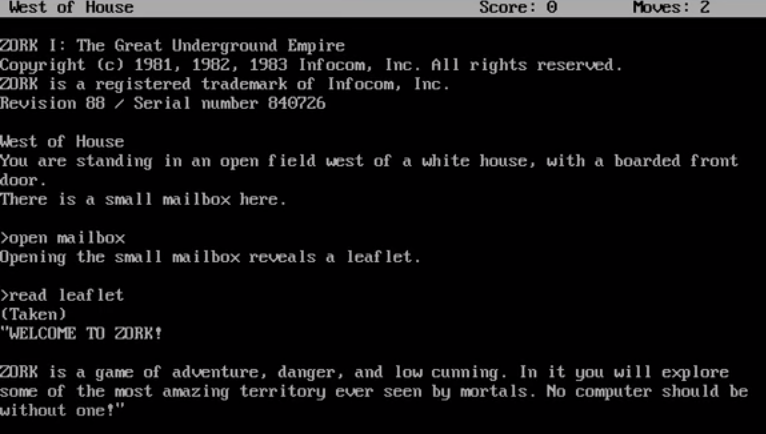

This move towards a spatialized fiction is not sui generis with Porpentine, though. First of all, it is important to note that there was half a decade of work made on Twine before With Those We Love Alive arrived, and that much of this work set a touchstone that Porpentine has followed. But the history of interactive fiction is even deeper than that. Indeed, some of the very earliest computer games, such as Adventure (1976) or Zork (1980), communicated their worlds only through text and both described dark underground labyrinths and passages.

In the heady early days of the popular internet a loose collection of literary writers began taking up the mantle of “hypertext fiction”. Works like Michael Joyce’s Afternoon, a story (1987) and Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl (1995) were innovative in their use of hyperlink to produce a fragmented post-modern structure for the reader to explore, but these stories were more about textuality than space. In some ways I think that more recent Twine games split the difference between Zork and Shelly Jackson: the structural grace of hyperlinks (over the clunkiness of the parsing systems of old-school text-based games) combined with the groundedness of placing a character in a specified, detailed environment.

a new sort of literature

Other developers are using Twine’s structures to tell stories about, and in, space. In 2015, developer Orihaus released To Burn In Memory, an “ahistorical and atemporal Interactive Fiction” set in an unreal European city just before World War I. The architecture of the story is all promenades and mezzanines and arcades, producing a sort of labyrinth of 19th century cultural memory, as if Jorge Luis Borges and Walter Benjamin collaborated on a sequel to Adventure. Memories and time literally intrude on the spatial text of To Burn In Memory in the form of pop up windows featuring diary entries from unseen characters. That Orihaus developed the game without Twine, but still used its hyperlinked structures is a testament to the simple power of Twinescaped literature.

I should say too that not all interactive fiction is like With Those We Love Alive. Some Twine games like Zoe Quinn’s Depression Quest (2013) and Anna Anthropy’s Queers In Love At the End of the World (2013) are deeply engaged with temporality, both interminable and minute. A lot of interactive fiction games aren’t developed in Twine, nor do they all use Twine’s link structure. However, I believe that With Those We Love Alive, and its predecessors and successors, opens up new vistas in the formalization of space, and might well be a new sort of literature.

As for me, I’ve got to close up here and get back to work on my new novel. I’m twenty pages deep and things are looking pretty good. What can I say? I’m married to the sea.

Header image: With Those We Love Alive node map via Twine Garden