Uncharted 4 has no regrets

There’s a brief moment in the first hour of Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End where Nathan Drake, a retired treasure hunter, combs through the artifacts from his adventures that he keeps in his attic. The space is ruined with meticulous clutter—each individual relic a callback to some grand excursion—and as I explored this makeshift museum, I found myself falling prey to the same fond memories that overtake the game’s protagonist.

Sifting through this digital archive prompts Drake to discover his old holster, now holding a toy gun. Almost instinctively, I make him pick it up, and then I steer him as he darts between shelves of memories and shoots plastic balls at imaginary enemies. Soon, however, Drake shelves his weapon and remarks that he’ll clean up the mess later. It’s a brief moment of childish fun, but, in the end, I guess he has to grow up—until, of course, he doesn’t.

///

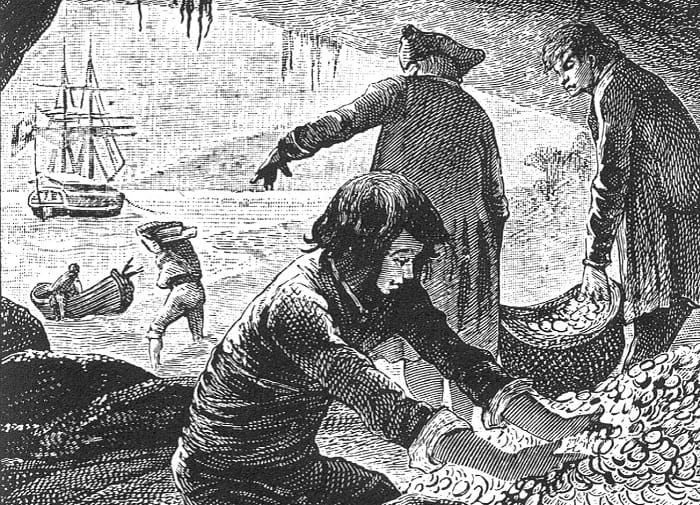

One of the enduring charms of adventure fiction is that it never hangs around long enough to age, or at least not in the same way as other, more “literary” fictions. Robert Louis Stevenson and H. Rider Haggard do not have the burden of timelessness; we can enjoy them as escapist diversions, bizarre artifacts from a particular time that now seem almost as ancient as the ruins that populate their pages. The study of adventure fiction is more often the study of empire, colonialism, racism, and the legacies thereof than the study of aesthetic genius. Treasure Island (1883) and King Solomon’s Mines (1885) endure as fodder for easy reading and popcorn cinema as we tell ourselves that the values they communicate remain in some distant past.

Illustration from Treasure Island by George Roux, via Wikimedia

That past catches up to Naughty Dog, the team behind the Uncharted series. When Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune (2007) released, it wore its pulp influences on its tattered, sweat-soaked sleeves, seeing Nathan Drake and his partner Victor “Sully” Sullivan blow up ancient ruins, shoot pirates, find the cursed treasure, and get the girl. Sure, it bore the ghosts of exoticism and the peculiar brand of racial problems of its predecessors, but most have accepted these missteps as the game’s commitment to the sloppy legacy of its genre. Drake’s roguish charm reappeared subsequently in Uncharted 2: Among Thieves (2009) when its cinematic bravado erupted across Tibet, using a troubled country’s crumbling traditional architecture as a backdrop for explosions and gunfights. By his third major outing, Uncharted 3: Drake’s Deception (2011), the exploits of the series’ protagonist began to wear a bit thin. Smirks and witticisms can hide reckless destruction of antiquity and mass murder for only so long before one starts to notice the cracks in the genre mold that Naughty Dog uses for each entry in the series.

Naughty Dog waves this penitent iconography with a heavy hand

Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End is, in some ways, the studio’s attempt to see if Drake and the genre that it has explored with the series can, in fact, mature. After a tiresome first hour that tries to introduce Drake’s brother, Sam—whose absence in the series’ previous entries never stops being suspicious even after the game’s trite explanation for it—we see Drake at a menial job with a boring but pleasant domestic life with his wife Elena, the treasures from their previous exploits tucked safely away in the attic. When Sam returns and propositions Drake with one last adventure, this time in search of a treasure they sought together over a decade prior, Drake’s initial misgivings crumble under the weight of familial obligation and a pathological need to cultivate his own legend.

The latter proves the more convincing motivator for Drake and for Naughty Dog, too. Moving away from the more fantastic settings of the previous entries, the stakes in Uncharted 4 feel more personal, the quest more grounded. The magical cities or mystical artifacts that began each of Drake’s prior adventures are replaced with a simpler macguffin: the treasure horde of Henry Avery, a pirate who marks his trail with statues and artifacts bearing the likeness of Saint Dismas, the repentant thief crucified alongside Jesus Christ. Naughty Dog waves this penitent iconography with a heavy hand, but this is not a series known for its subtlety. From its onset, Uncharted 4 insists that it will be Drake’s final adventure, investing even the most bombastic moments—from an Ocean’s 11-style auction heist to a car chase through a Madagascar market place—with a tinge of bittersweet resolve.

This air of seriousness, however, never attempts to elevate the game above its pulp trappings. That is, in an effort to make a more mature game, Naughty Dog doubles down on the adventure fiction tropes it has spent so many years attempting to perfect, focusing its efforts on meticulous detail to achieve a remarkable level of fidelity. Grass bends realistically as Drake and Sam hide from patrolling mercenaries. Mud convincingly clings to Drake’s clothes as he gets dragged behind a vehicle. Props and pieces in any given locale beg to be considered with a careful eye, even as Drake sprints past them to dodge a hail of gunfire. This obsession with visual minutiae seems all the more impressive when the game’s camera languishes over the grand vistas of misty Scottish cliffs or the lush green of a Madagascar jungle.

Many of these visuals splash across the screen during scripted moments, of course, but there are areas that offer at least the illusion of openness. Driving across the rocky terrain of Madagascar with Sully and Sam in the passenger seats, it’s possible to take brief excursions to ruins that dot the landscape, and in these quiet places between explosive firefights, I almost forgot that I was being funneled along a narrow narrative path. As I used a winch to pull the jeep up a steep mud bank, I found myself wanting more opportunities to slow down and explore at my own pace without the inevitable gunfight interrupting my own adventure, one with a bit more introspection than the game’s genre would ever allow. Like so many works of adventure fiction, Uncharted 4 hints at a much larger, more complex world, but it is only ever concerned about a small part of it—namely, those parts ripe for plunder.

Uncharted 4 never pretends to be anything other than the sum of its highly-polished parts

As a result, Uncharted 4 falls back on predictable story beats pulled straight from the hallmarks of its genre. While there’s enjoyment to be had swinging from a rope, spraying rounds of ammo like some gun-toting Errol Flynn, the game’s overlong sequences of gunplay become tedious, especially in its third act. Treacherous ledges crumble with clockwork regularity in nearly every climbing sequence, and a laughable number of environmental obstacles require using the same type of crate to surpass them and reach new areas. By the game’s end, there are no more surprises, each encounter funneled down a narrowing alley of gunfights and cliff jumping that mimic the easy, digestible parts of adventure fiction. Any more self-doubt or confusion about motivation would shatter the illusion that Drake and his crew pursue anything more profound than a pile of gold and a story to tell.

That’s one of the limits of basing an entire franchise on a genre of fiction known for recycling locales and themes, I suppose. But Uncharted 4 never pretends to be anything other than the sum of its highly-polished parts. Its initial aim of interrogating the ability of adventure fiction to mature seems assured in the knowledge that it doesn’t need to. Pulp fiction has always been produced with the knowledge that it inevitably become trash, consumed and then thrown away, but Naughty Dog treats the genre with such confidence that it dares us to dismiss it. Uncharted 4 offers nothing profound, assured in its own way that it has nothing to prove.

In this way, Uncharted 4 has more in common with the works Haggard or Stevenson than it does the throwaway magazines of the 1940s-60s, being a well-made example of an ephemeral genre. That’s why, out of all the game’s explosive moments, I remember Drake’s time in his attic, playing with a toy gun in a museum of his own past. In his attempts to recapture a bit of his old self, he realizes that he can, indeed, grow up, even if his adventure fiction legacy cannot. As impressive as it is, it remains an artifact more suited to a curiosity cabinet than a model for a way of life. For him, and for Naughty Dog, too, that’s enough.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.