The uncomfortable politics of the "Ludic Century"

Sitting in front of a giant iMac screen, it’s easy to forget that not everyone owns a computer. In fact, reading this piece on a webpage, it’s even easier to forget that the majority of the world population doesn’t have internet access. That means no email, no Twitter, and no Farmville.

Who comprises the “we” defined by the information age, and the “we” that play games now more than ever before?

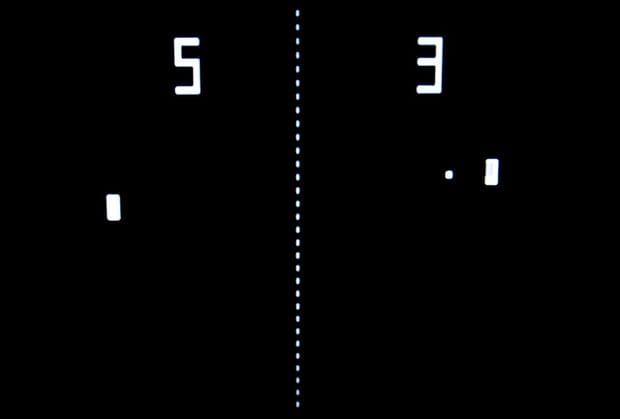

It is with the so-called “digital divide” in mind that I approach Eric Zimmerman’s much ballyhooed “Manifesto for a Ludic Century” with some skepticism. Zimmerman wrote the manifesto after years of conversation about games, and it appears in an upcoming book entitled The Gameful World. The manifesto is rich, well written, and idealistic—as it should be. There’s plenty of provocation, and so many great ideas that deserve interrogation and reflection. Zimmerman’s primary thesis is that we are entering a new age wherein games are appreciated with a newfound importance. He states that in the 21st Century, we move beyond just working with information and information technologies, but we must increasingly play with those systems. At the heart of the manifesto are two, uncomfortably broad claims: that we play games more now than ever before, and that we are emerging from an era defined by information.

But to what monoculture is Zimmerman referring? Who comprises the “we” defined by the information age, and the “we” that play games now more than ever before? Maybe the manifesto is for Americans. Of course, in rural America, where the local high-school football game is still attended live, not watched on a stream with a chat window, the information age ideas of the manifesto seem less applicable. Or maybe the manifesto is just for the so-called Western world, folding in the privileged Europeans? But then again, that would leave out Japan and other Asian nations, where digital technologies thrive as much as in the west, and where digital games are a massively important part of many cultures. So the thread tying the “us” together seems to be this idea of “digital technology.” The manifesto is really just for the minority of the world with computers, for whom the impact of digital information technology is most felt.

Maybe more importantly, who is left out of the Ludic Century? Are underprivileged cultures, without access to digital technologies, and even with limited access to “published” board games, not also a part of this future? Claiming that “increasingly, the ways that people spend their leisure time and consume art, design, and entertainment will be games” presumes that for so many people games were not already a primary source of entertainment, even without computers or Ticket to Ride. Zimmerman acknowledges right at the start with the first statement that “games are ancient,” but then, why is this century the Ludic Century? For millennia cultures have been playing games, and watching games, and talking about games, listening to games on the radio, writing poetry about games, and painting images of games on urns, and ritualistically incorporating games into their culture. So why now? If the answer is “technology” then we must ask who is left out of this vision of the future.

While inevitably things will change faster than imagined, history suggests that all new technology will not be democratically distributed around the world.

Perhaps the suggestion is that in the 86 years left in this century, digital technology will rapidly spread, bringing new games to everyone! While inevitably things will change faster than imagined, history suggests that all new technology will not be democratically distributed around the world. Smartphone penetration in Africa—all of Africa, mind you—is estimated at somewhere between 3% and 17%. Internet usage estimates in Asia grew by 841.9% between 2000 and 2012, but that still represents only 27.5% of all the people in the continent. These are unscientific estimates at best, but they suggest if only anecdotally how severe the global digital divide is. I should point out, too, that the digital divide is not just about access, but also about utility, which reiterates the importance of asking how commodified technology in a capitalist world leaves many disenfranchised, and disconnected.

Technology (loathe as I am to use the word as an unqualified noun) is inextricably wrapped up in capital relationships, and cultural power dynamics. The cycle of obsolescence does not empower underprivileged cultures, upon whom outdated technology is so often discarded. This has been one lesson from One Laptop Per Child, an idealistic vision that can’t clean itself of the residue of imperialism. If the Ludic Century becomes manifest because of a global spread of technology, it may still mean that the majority of the world will enjoy it less, or find less use for such a paradigm, and subsequently still struggle.

There is, of course, some irony in a manifesto for the privileged classes. Zimmerman recognizes the weaknesses of the term “manifesto” and, as he wrote in a comment on his own piece, he admits that a declaration of a Ludic Century from a game designer is “self-serving.” It’s an important and humble admission that unfortunately falls a little short.

There is, of course, some irony in a manifesto for the privileged classes.

It is not just that claims for a Ludic Century are in the interest of a stakeholder in games. Rather, we must consider how such claims support the positioning of games as part of a broader “games-industrial complex” that reinforces hegemonic notions of a game as a commodity. There’s a very interesting parallel here to sports (which are games, after all), which have become so commoditized by way of the media through which they are predominantly consumed, that to speak of sport without also referencing media is incoherent. Amazingly, it took until the 1970s and 1980s before sports studies caught up to critical cultural studies, and scholars like Jhally and Wenner began to apply a socioeconomic cultural critique of mediatized sport. It’s yet another reason why I think game studies and sports studies should cross-pollinate more.

Knowing Eric only just a little bit, but more familiar with his work, I don’t for a second believe that he thinks games are the province of the privileged classes. However, by framing a case for a Ludic Century around notions of an information revolution, and increased interest in games driven by digital technology, he paints a vision of the future that leaves the vast majority of the world out. In many ways it is reminiscent of the assumptions made about print culture and the Gutenberg press: that the world exploded in literacy and wisdom with the re-invention of print technology. While a popular thesis for some time, it has since, in my estimation, been thoroughly dismantled by critics who point out the Western focus of the argument. Prometheus did not gift humanity the computer. Maybe the truth is that while information technology has impacted how privileged cultures with access think, talk, write about, and play games, that boulder of a paradigm shift is barely a ripple to those outside that world.