Throughout the Metroid series, Samus Aran’s trusty yellow-and-orange power suit undergoes countless changes: Varia Suit for lava, Gravity Suit underwater, Zero Suit for stealth, Fusion Suit for dexterity. The constant, of course, is the woman inside it. Putting aside the ill-advised character development of Metroid: Other M, Samus is an enigma. We know how she moves, how high she can jump, and briefly glimpse her face reflected in her visor, but that’s it. Perhaps there’s a bitter irony in one of videogames’ most prominent women being utterly mute, but there’s also resolute strength in Samus’s incessant forward push, her unerring athletic and combat prowess ensuring her survival in the universe’s most inhospitable climes.

Axiom Verge situates itself comfortably in the Metroid tradition. Protagonist Trace is a man, and he talks (via text bubbles), but initially he’s also weaker and less capable than Samus.

Axiom Verge situates itself comfortably in the Metroid tradition

His first “power suit” is a lab coat. He has a stubby, weak health bar. He’s constantly bewildered in dialogue. Trace doesn’t understand anything about his situation, and the first thing he speaks with—a huge Masamune Shirow cyborg head that speaks in arcane gibberish—doesn’t really clear things up. The game opens with Trace’s death in a lab accident, and his soft science-man body is reincarnated in a biomechanical hell, where he’s left to his own devices—and boy, are there a lot of those devices.

The defining characteristic of a Metroid-like game is the relationship between upgrades and the environment. Areas will be impassable until the player receives a given upgrade, and when she does she has to make her way back to that slightly-too-high ledge, that suspicious patch of textured wall to try that set of power boots or that beefed-up bomb. The game necessarily doles out a lot of upgrades to keep the player moving forward through previously inaccessible areas.

But Axiom Verge’s guiding principle, as mentioned by one-man developer Tom Happ to Gamasutra, is: “Am I doing this just because it’s tradition, or because it actually serves the game?”

Because Verge builds on the bones of Metroid, it’s instantly legible to anyone with any familiarity with those games, or any games that pull from them—a long list. This leaves it free to improvise. Metroid offers the changes; Axiom Verge plays the head once and then never looks back. Thus, as with recent retro success Shovel Knight, its tweaks to the melody stand out, even if the song is naggingly familiar.

What can make or break that gambit is: are you Kenny G or John Coltrane? Happ’s vision—frankly, his good taste—positions him closer to the latter. He’s toying with a genre he knows inside-out, like de Palma’s endless Hitchcock variations, knowing where to directly reference, as with the crab-like enemies that circle platforms exactly like they do in Metroid, and where to riff, like a small controllable spiderbot that plays off Samus’s morph ball. And he shows the same sure hand with aesthetics as he does with mechanics, taking the Gigeresque implications of Metroid and spinning them into a world that bristles with the obsessive detail of a prolific mangaka.

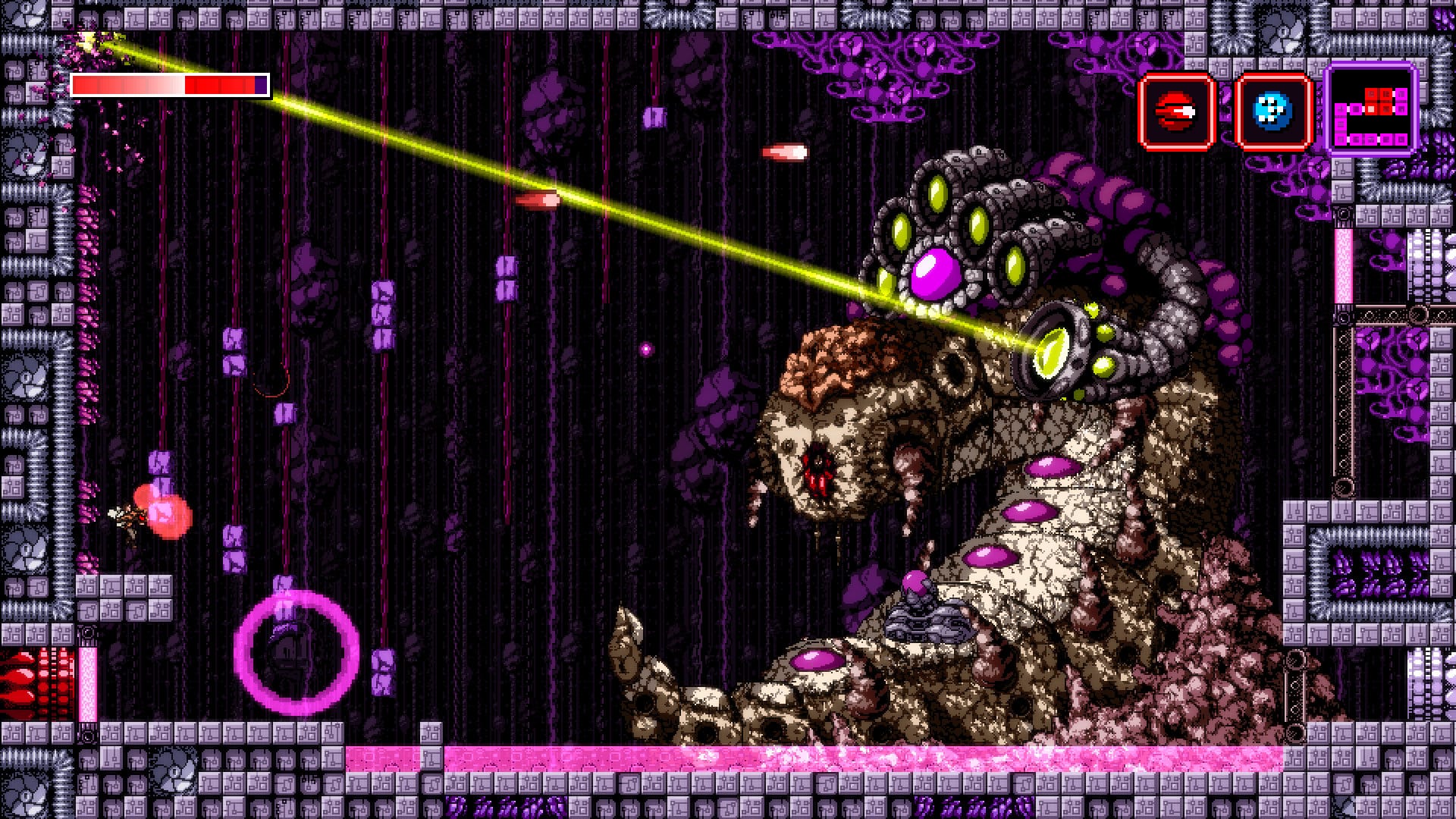

Bosses are massive, increasingly bullet hell-esque affairs, filling the screen with lasers and bombs, their sheer size requiring the camera to pull back from its usual distance to fit them into frame. Their bodies—largely repulsive marriages of flesh and metal, organic shapes twisted into chitinous weaponry—quiver and roil with life, every pixel in motion, a display of mad imagination.

Each area features its own distinct theme, as you’d expect, but executed with panache. The music in particular is bass-heavy and ominous—”Inexorable” has a vaguely Middle Eastern-via-Hans Zimmer vocal synth that flutters like Busta Rhymes’s “Arab Money,” of all things, and “Trace Rising” owes a debt to Kenji Yamamoto’s work on Metroid Prime before turning into a strobing rave-up.

Be aware the game is mixed hot as fuck. If you don’t have to turn down your TV volume from its usual spot I salute you: there’s a jarring bitcrushed squall when Trace dies, as if he’s being broken down into his constituent molecules before respawning. It’s assaultive, but a nice touch, like the analog control on Trace’s drill (feather the trigger and the drill extends a little; squeeze it and it spins out to its full length), or the way bosses explode into shimmering clouds of voxels upon death, or how they and their surroundings grow increasingly, angrily red as their health decreases, or the hateful screams of a certain ape-like enemy as it flings itself at you, or the 8-way crunch of the shooting, even on an analog stick, which forces the player to position and lock herself before firing, or the strange mantra “DEMON, ATHETOS SAY, KILL” that bosses scream at you before attacking. There are many more.

If you don’t have to turn down your TV volume from its usual spot I salute you

Happ is adept at filling the world out with intriguing details like that. It’s a rich game that recognizes that Metroid was more than the sum of its mechanics. There is an upfront narrative, but there’s also a lot of textural shading that lends welcome ambiguity to the shooting and backtracking. The title screen of Super Metroid was a masterclass in this technique: scientists dead on the floor, a Metroid wriggling in a containment tank, and a Carpenter synth pulse on the soundtrack. Axiom Verge has that same allure, but Super Metroid came out in 1994. Verge is too smart to be a nostalgia trip, but it also, ultimately, sticks to executing the familiar with style. If it didn’t look so damn good, it’d be easy to say we’ve seen it all before.