Undertale, one year later

September 15th marks a full year since the arrival of Undertale, Toby Fox’s 16 bit-style role-playing game for PC. Its auspicious reception, which even delivered the game into the Pope’s hands, seems now more than ever to have been a flashpoint in current debates as to what constitutes excellence in videogames. Standing apart from the colossal world-building efforts that typically crowd year-end lists, Undertale offered something else: an epic-in-miniature, the latest entry in a tradition that might also include the animated shorts of David OReilly, Sarah Orne Jewett’s The Country of the Pointed Firs (1896), and Chopin’s preludes, which served as the inspiration for Jake Elliott’s short game Ruins (2011).

Like all these works, Undertale is both purposefully small and ferociously determined to transcend its own smallness. Henry James called Jewett’s volume, “a beautiful little quantum of achievement,” because of how economically her sequence of interrelated short stories evoked the dense lived history of Dunnet Landing, an isolated fishing village on the coast of Maine. David OReilly’s 2009 short film Please Say Something is a study in economy as well, intentionally using roguish animation shortcuts like preview renders, isometric perspectives, and low-poly geometric models, in order to tell a sweeping love story between cat and mouse. “One of the main problems with 3D animation is that it takes so long to learn and then to use, from constructing a world to rendering it,” OReilly remarked in a 2009 essay. “My goal was therefore to shorten this production pipeline to a bare minimum.” Chopin took a similarly irreverent, pragmatic approach to the classical form of the “prelude,” composing them as brief, freestanding pieces rather than introductory works. His shortest prelude runs just 12 measures, and most were so sparingly conceived that they moved an irksome Robert Schumann to comment that they were, “sketches, beginnings of études, or, so to speak, ruins, individual eagle pinions, all disorder and wild confusions.”

Wedding small objects to specific feelings is put to poignant effect

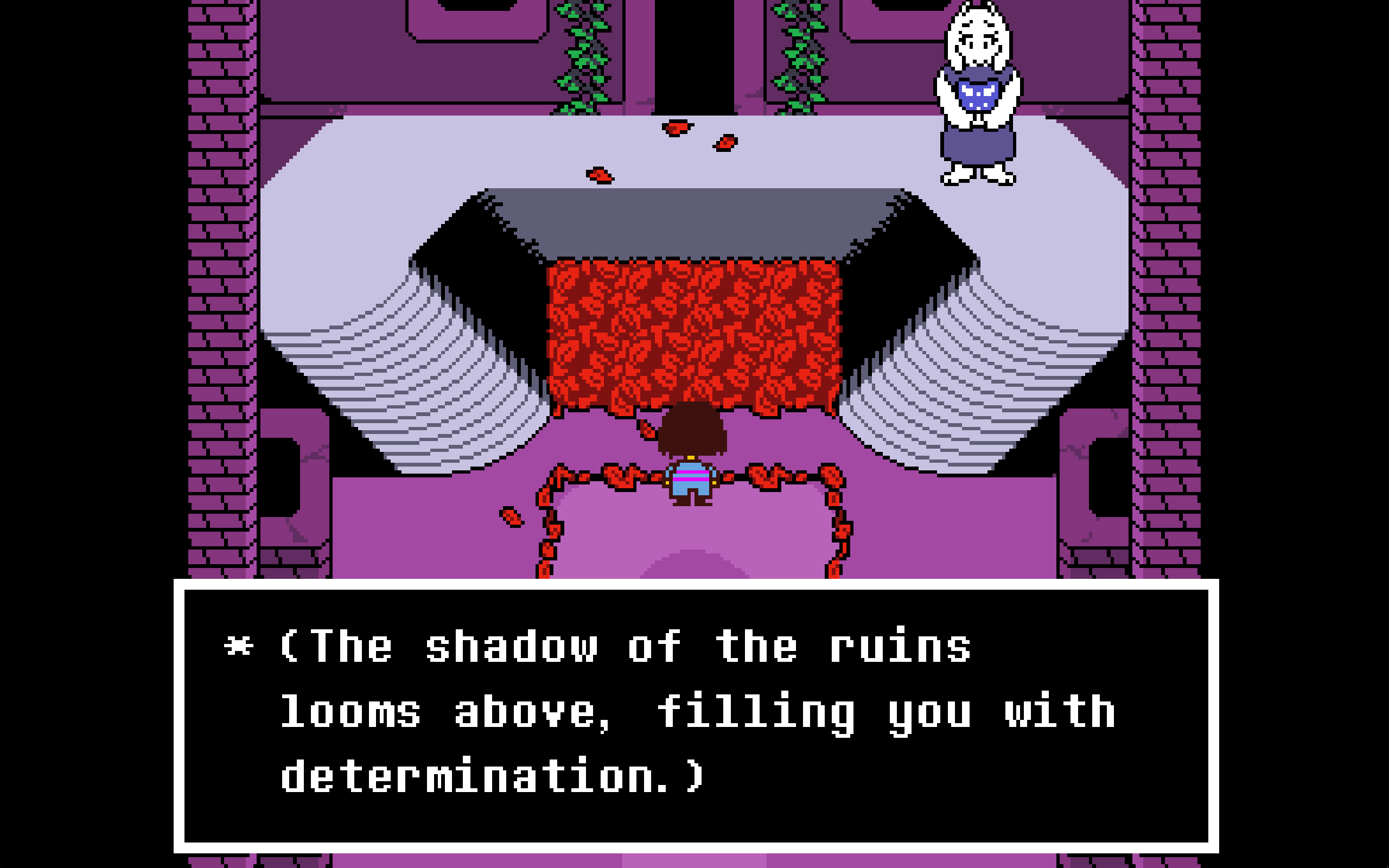

“Ruins” is also the name Fox gives to the first playable area of Undertale, which inhabits a spare, hermetic series of spaces, not unlike Jewett’s vision of Dunnet Landing, sketched in a way that leaves ample room in which to magnify the inner worlds of its inhabitants, each replete with unique hopes and dreams. Fox created Undertale’s landscapes and interiors using GameMaker: Studio almost entirely on his own over three years, filling its secretive, maze-like world with a host of tiny yet meaningful treasures. Walking around and inspecting all the objects on display (an anthropological practice also considered essential to Jewett’s literary style) is a reflex that can feel rote and automatic to RPG initiates, but Undertale aims to turn it into a kind of emotional odyssey, punctuated by the cumulative impact of each photograph, scrapbook, and memory.

Because small epics succeed when they wring universal truths from granular elements, scale is a crucial aspect of the game’s world. Small gestures, modest tasks, unique tokens, unassuming figures, curios, and minutiae of all kinds contribute to the grainy texture of the its emotional core. In one area, the player can bet on a snail to win a race, only to watch it heartbreakingly fold under the pressure. Item descriptions contain endearingly meaningless character details, such as the Temmie Flakes, which upon further inspection are “just torn up pieces of construction paper.” The game’s random encounters are menu-based “battles” with one-of-a-kind monster types, each with distinct fears and desires, who can be befriended rather than slaughtered wholesale.

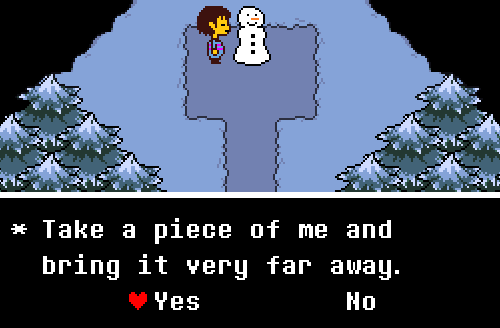

Becoming fluent in the game’s trivia—the way a particular character’s dialogue undulates across the screen, for instance—is both encouraged and rewarded. Wedding small objects to specific feelings is put to poignant effect time and again, whether it’s the force of a mother’s love distilled into a butterscotch pie or a small piece of a snowman that you can’t bring yourself to discard. One character cannot be befriended unless you decide to offer her a cup of water at a critical moment. In Undertale, these small decisions matter, albeit sometimes in ways the player could not possibly predict. Ultimately, the game is able to succeed because it infuses its austere spaces and 16-bit sprites with an epic depth of feeling rarely glimpsed in videogames.

extracting joy from the littlest, stupidest things

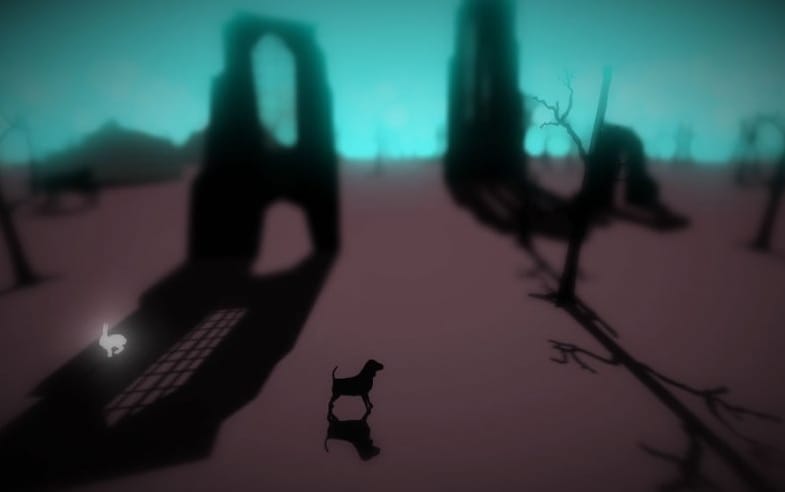

Small-scale works are often derided for feeling embryonic or unfinished, throwaway motifs or fledgling ideas that the artist failed to integrate into a sufficiently ambitious whole. Game designer Jake Elliott, who drew the title of his Ruins from Schumann’s appraisal of Chopin’s preludes, defended their proportion in an interview: “Maybe [Chopin] felt like they were complete objects, but there wasn’t a vocabulary for talking about pieces of music that were short at the time. Their length is what drew me … there is a lot that’s unspoken.” Having conventionally privileged length, magnitude, and formal unity, games too have left critics bereft of a clear rubric for evaluating intentionally abbreviated, serialized, even disorderly exercises in interactive design. As games have inched steadily toward simulating the infinitely huge world—a feat that the procedurally generated universe of Hello Games’s No Man’s Sky took to its (il)logical extreme—games like Fox’s Undertale and Elliott’s more widely known Kentucky Route Zero (2013) have deliberately chosen impressionist, circumscribed, “underground” milieux as their settings.

That game-worlds are at once radically expanding due to hardware improvements, and imaginatively shrinking due to emergent design philosophies, suggests a potential rift in the medium that Elliott compares to the transitional moment in 19th-century music away from Neoclassicism and toward Romanticism: “[The Preludes] came at the beginning of the Romantic period … The game ideas I’m working with, as well as the games I am playing right now, are similarly moving into Romantic and more expressive territory, instead of being overly formalistic.”

Ruins, by Jake Elliott

One of the prime advantages of smallness, then, is that it can help liberate ideas from the tyranny of formal expectation, allowing more expressive concerns to flourish. When Chopin released the prelude from its conventional purpose, he inaugurated a charismatic new approach that treated the form as a kind of “mood piece,” influencing generations of composers to follow. Although the Romantics were no less interested than their Neoclassical forebears in capturing the complex and the infinite in their aesthetic forms, they modeled their art primarily after the jagged emotional landscape of human consciousness, in all its moody, restive glory. Using a particular emotional or cognitive state as the guiding force behind level design has proven not only a stimulating creative challenge for game makers, but also an attractive approach for small teams on Kickstarter budgets who lack the resources required to code massively detailed open worlds. Like minimalist composers or judicious fiction writers who prefer to sketch by omission, game creators are becoming more confident that withholding embellishment and cabining scope can be powerful ways to build a world that evokes a precise emotion or reaction. According to OReilly, an ardent defender of simple and even crude animation styles, “The more elemental and simple an environment, the more exciting and visually rewarding it is when we introduce changes to it.”

Undertale deposits you in a radically simple and lonely circumstance—a fallen human in an underground world, alone in a black void with a soft pool of light in the middle. Although the mother figure Toriel offers you a home, the game only truly begins if you manage to flee her solace and rededicate yourself to the adventurous and life-giving task of being alone in the unknown, a humble visitor in a seemingly vast world. Having left Toriel behind, each of the game’s save points generates further reasons to “stay determined,” each more memorably inconsequential than the last: “The feeling of your socks squishing as you step gives you determination,” “Partaking in worthless garbage fills you with determination,” “Playfully crinkling through the leaves fills you with determination.” If Undertale can be said to have a moral or an ethic, it might be this: extracting joy from the littlest, stupidest things—especially those things—can be a strategy for enriching our lives, refining our ability to relate to others, and cultivating resilience in the face of loneliness. Whether it’s listening to Napstablook’s “spook-tunes,” telling Alphys you’ll watch her favorite TV show, or reassuring Papyrus that you like his “Cool Dude” t-shirt, these modest acts of goodwill accumulate and give rise to delicate seedlings of friendship.

videogames can feel like a crowded refuge for the lonely and isolated

Undertale, in its quest for the humanity that distinguishes the epic in all its forms, becomes a simulation of loneliness. Its most distinctive mechanic, which allows the player to choose mid-battle whether to kill or befriend the game’s “monsters,” allegorizes the riskiness inherent to human sociality by leaving the player constantly open to attack. Emotional pedagogy is not something we tend to expect from videogames, but at its most epic, Undertale manages to capture the magic that transpires in those rare and fleeting moments, seemingly only rarer with age, when we disarm ourselves in order to welcome others. Those moments—in game as in life—are sometimes exceedingly hard-won, and the game’s complex “bullet hell”-style battle system smartly (and often tenderly) evokes how difficult it can be to navigate the minefield of another person’s neuroses, prejudices, and assumptions.

When faced with two hostile royal guards, for instance, the player must avoid conflict by puzzling out a peaceful resolution, which entails cleaning the second royal guard’s armor until it shines, and then asking the first royal guard to be honest with his feelings. Having performed these small gestures, the battle music halts and a sentimental theme begins, as the two guards haltingly confess their affection for each other: “The way you fight … The way you talk … I love doing team attacks with you. I love standing here with you, bouncing and waving our weapons in sync … I, like, want to stay like this forever …” By encouraging seemingly minor, selfless acts, Undertale’s battle system neatly expresses how they can be precursors to forging a meaningful connection with another, and that the risk can be worth the reward.

In short, it teaches us how to be less lonely.

The lesson is important because loneliness is here to stay. In an interview with The Guardian, John Cacciopo, the director of the Center for Cognitive and Social Neuroscience at the University of Chicago, defines loneliness as “perceived isolation.” His findings on its impact are striking: loneliness typically affects one in four people, can be contagious, and has a public health cost comparable to obesity or tobacco use. The topic of loneliness has been raised often in relation to videogames, given their remarkable potential to provide an engaging social and emotional outlet for people who are alone, or feel isolated. At the same time, they run the risk of re-entrenching those vulnerable to feelings of isolation and alienation in familiar emotional terrain. As a result, videogames can either feel like a crowded refuge for the lonely and isolated, or a remote satellite of their own. Toby Fox, for his part, has publicly acknowledged what he hoped Undertale would achieve. Two months after its release, he tweeted, “Hearing ‘UNDERTALE made me want to be kinder’ or ‘UNDERTALE helped me through a dark time’ feels more valuable than any award or score.”

Whether games are drifting toward a kind of expressive or Romantic era is unknowable, but if Undertale’s success is any indication, more and more designers are experimenting with formal limitations in order to express messier and more suggestive emotional states like melancholy, alienation, loneliness, and nostalgia. This experimental domain is where Undertale resides. One year later and it almost seems inevitable that a game that revolves around small acts of kindness and charity would wind up in the Pope’s hands. Near the eve of the game’s one-year anniversary, Fox wrote, “UNDERTALE’s almost a year old. Somehow, I feel both ‘wow, didn’t it just come out?’ and ‘THAT WAS BY FAR THE LONGEST YEAR OF MY LIFE.’” The confused proportions ring true for a game that delights throughout in attending to matters both big and small, a quantum achievement with epic heft.