Unravel wants to help us mourn, but doesn’t know how

Unravel begins with a letter from its creators that thanks you for purchasing the game. It explains to you the power of the medium, the senses of love and loneliness about to be explored, and how long they as a team have been pouring their hearts into it. The font and spacing makes it resemble the prelude to Thriller (1983), where Michael Jackson promises that he does not worship the devil.

A game that signals its own history and globe of emotions as active parts, Unravel began for audiences last year when Coldwood Interactive’s creative director Martin Sahlin was called to the stage of EA’s E3 keynote, as if it was his turn for show-and-tell. Like a schoolkid, Sahlin was earnestly and visibly anxious, his hands rattling while holding up Yarny, his star, a Funko Pop-sized wad of craft stuff shaped like a cat or a devil, with beady white eyes that look perpetually sad.

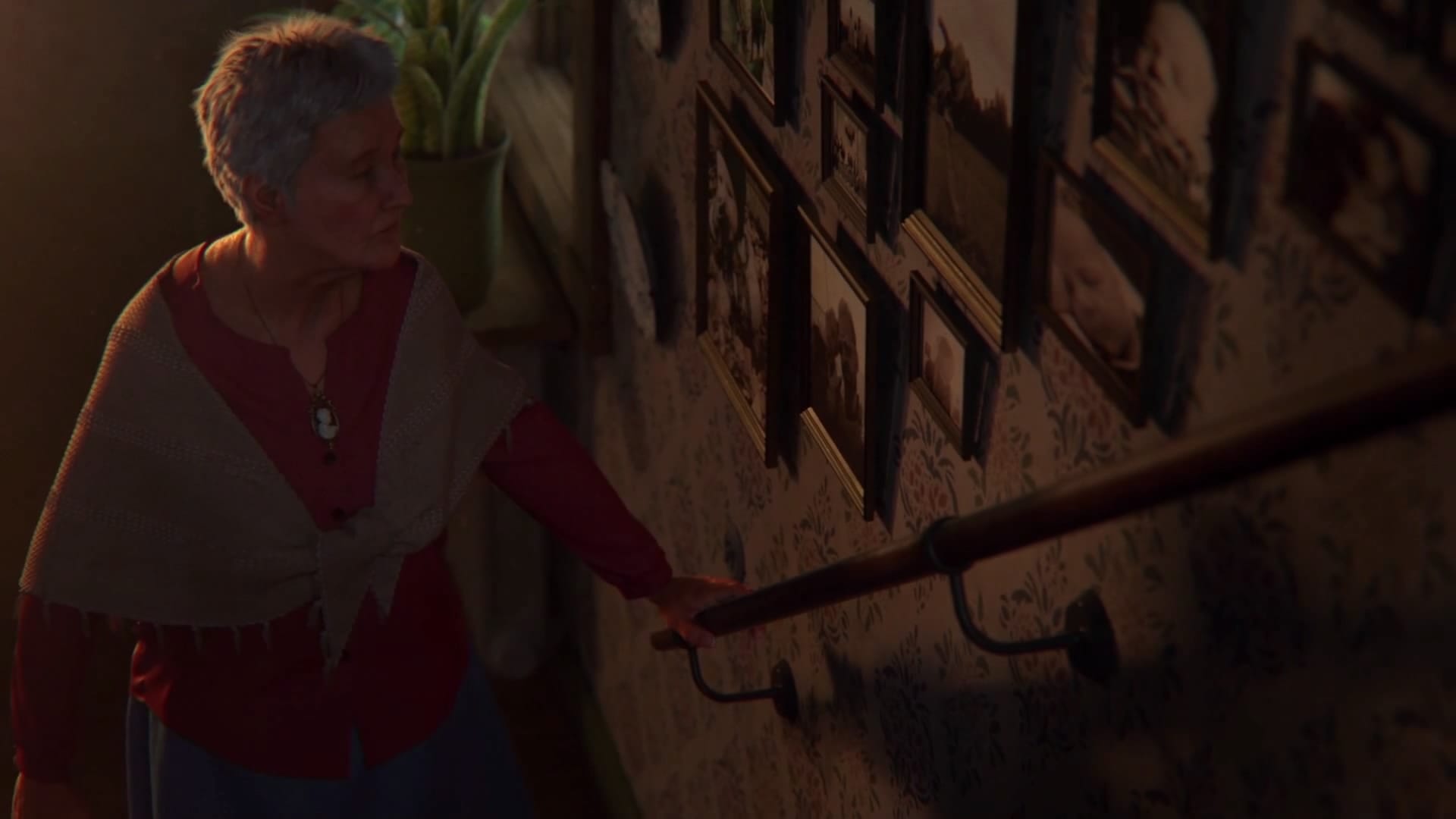

After the preamble and the curtains lift, you meet a grandmother longingly walking along the stairs of her warm cottage home. She glances at photos of children who once visited more often. And at that moment you know exactly at which junction this is going to end.

///

We’re very raw when we mourn. I don’t think people really consider the true malleable lumps they become, the way they sort of recede into a shell so as not to stumble through any more motions. Momentum is hard; you almost desire manipulation because it’s easier, to be given answers for your pain when there likely aren’t any. I’m there right now. It’s what’s going on. The family has been dented and we’re all still in the aftershock, figuring things out.

This couples a recent cultural tendency to project sentimental connections onto multimedia, as if the eerie coincidence of a TV drama’s syndicated subject matter is akin to it catching our bodies when we buckle. It’s just logistic contention and then a digital placebo. I’m being mean, of course—it can work both ways. Years ago, watching a new Clone High (2002-2003) on the second night of shiva seemed like a solid break. We couldn’t have expected that the running gag of that episode was JFK’s teenage reincarnation sobbing uncontrollably over the Ponce de León, a character introduced only to die comically. My brother, my cousins, and I whiteknuckled through the first half, glancing at the backs of each other’s heads, waiting for someone to change the channel on everyone’s behalf. That episode still isn’t as funny as I know it is.

///

The editorial staff here knew I’ve suffered a loss. They have never meant me any harm, especially not over assigning reviews. They just didn’t know a videogame starring a precious felty doodad sets its final level at a funeral.

At least, the final level of Unravel is in front of a funeral. In the background, sparkling images of sad human processions glow among the tombstones. In the foreground, the ol’ stone-faced Yarnster deals with wind obstacles similar to Gusty Glade in Donkey Kong Country 2 (1995). In the background of other stages I saw grandchildren sit among the wonders of nature and family while in the foreground I navigated block puzzles and was chased by a rabid hamster. In Unravel’s weirdest detour, the first of the many feel-bads, I watched nature take a hit from humanity’s pollutants, literally manifested as guys in hazmat suits and glowing green vats of acid sludge. In terms of subtlety, it scores higher than Captain Planet, but lower than Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II: The Secret of the Ooze (1991).

Unravel’s a pile of travel package photos

In the background are memories—literal family vacation photos commissioned by the game’s creators—deconstructed into constellations of light. In the foreground is Yarny, who never breaks eye contact as it scampers back and forth like Bugs Bunny singing “This Is It.” In the background are broad strokes of empathy, generalized “moments” that play a chorus of violins. In the foreground is a pretty mild videogame, controls that do feel like you’re wrestling with floaty fuzzy weightless mess makers, with softball puzzles and, in contrast, breakneck action sequences that are unfairly clinching.

Yarny is a kind of a Forrest Gump figure to the world around it, minus the aphorisms and plus a knack for getting eaten by birds. Yarny rarely interacts with the emotional highs (sunny family good times) and lows (dark and gloomy deaths on personal and global scales) on which this game is apparently based. Hell, Yarny barely looks at them. Either the context or the game is a subtitle track to a different feature.

I am not doubting the sincerity of Coldwood. They’re a small team with a portfolio of sports and fitness games who are pursuing the distressing path of honesty, and emotional honesty is a good direction for most videogames. Between my states of tragedy and theirs I’m sure we could have a constructive chat, but nothing about their game has benefitted. Honesty and quality are two different traits with different exchange rates. I’m currently a soft emotional waterballoon who will work off the shiva rugula when I stop sleeping until noon and I haven’t even squeaked playing through Yarny’s magical journey. I cried at the end of My Dog Skip (2000) and I don’t even own a dog. Here I felt (give me this one pun) nothing, which isn’t a failure unless that’s a work’s key investment. Unravel’s a pile of travel package photos, and could actually take a few notes from McDonald’s ads on how to sell personal moments largely unrelated from the product they’re interacting with.

Despite all of its cutesy posturing and promises, Unravel is still looking to fill some kind of void. And I’m not sure if that void is its shortcomings as a mood board, as a videogame, or a cloying digestible basket of “feels” for EA.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.