Zach and Jess love horror movies. Zach and Jess love videogames. Until Dawn, a game that has been gestating since 2012, promises to blend these two things together. By combining motion-captured actors and choose-your-own-adventure-style gameplay, Until Dawn wants very much to be a Cinematic Horror Experience. Zach and Jess were wary about this, until they talked it over. Below, they discuss how Until Dawn complicates one of the most famous tropes of the slasher flick experience: identifying with the final survivor.

///

Zach: The question for me with Until Dawn is: are slashers even compatible with videogames? The crux of those movies is audience identification with a single character who possesses the resilience necessary to make it out alive.

Sally in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre barely escapes death, but her constant, propulsive will to survive gives her the edge over, say, the guy who enters the red room of death only to get unceremoniously smacked on the skull with a meat tenderizer. She full-on throws herself through two windows to get away from Leatherface. Ripley, Laurie, Nancy, Stretch: they’re all survivors.

Jess: For those of you who missed Carol J. Clover’s seminal work Men, Women, and Chain Saws, we call this the “final girl” trope. Because all the ladies you mentioned (and many more) actually have a lot in common: they’re all young, sexually unavailable, somewhat intelligent women who surprise audiences with their moxie and ability to avoid fleshy, sledgehammer-wielding pig-men. The final girl drives home the tension in the last act of a horror movie, as viewers are left to worry about whether she’ll survive or bite it like everyone else. Regardless, we go through the final girl’s ordeal alongside her, identifying with her no matter the outcome.

only to get unceremoniously smacked on the skull with a meat tenderizer

Now, Until Dawn sounds like an extension of the final girl trope, making players identify and feel responsible for a total of eight characters (four boys, four girls). Which, frankly, sounds anxiety-inducing.

Zach: It is. I’ve played this, you haven’t, so let me briefly summarize. You control a large cast of characters in a Telltale-style choice-based game, but you’re paired off with another person most of the time. So you and a friend are fixing the power in the basement, or you’re getting steamy with your girlfriend in a cabin, while the rest of the characters are doing their own thing. You’ll pop back and forth between them, occasionally jumping around in time to cover everything.

The setup is this: a bunch of friends have gathered at Josh’s parents’ big dark house in the snowy woods. It’s been one year since Josh’s two sisters died in a bizarre incident. And, as they cuddle and fight and explore, something is out there with them.

I was worried, before playing this, that it would be a stiff, dumb recitation of horror tropes. But the acting really sells the game. Characters are expressive when they speak; the banter is often pretty funny. There’s only one character so far who I’d be totally okay with suffering a terrible death, and the game almost perversely sidelines her to put the likable people in danger again and again.

Jess: From the clips, demos, and trailers I’ve seen, the ghost of the final girl trope seems to still haunt both the characters and the player. Conceivably, they could all be the “final girl,” left to struggle for life alone in the face of axe murderers and/or Saw-like morality tests.

Also, it’s important to note that while Clover thought the final girl trope produced mostly positive effects by asking a predominantly male audience to identify with a female character, there’s a shitty reason behind why the trope even exists. Since the final survivor must show abject fear, Clover theorizes that audiences feel too uncomfortable watching a final boy show such a vulnerable emotion. The horror we feel over the final girl’s ordeal is intensified because of her exterior femininity and fragility, while the hyper masculinized monster unleashes some untapped patriarchal power deep within her. We’re more comfortable watching a masculinized woman survive a horrific event than having to watch a man reduce himself to something as girly as fearing death.

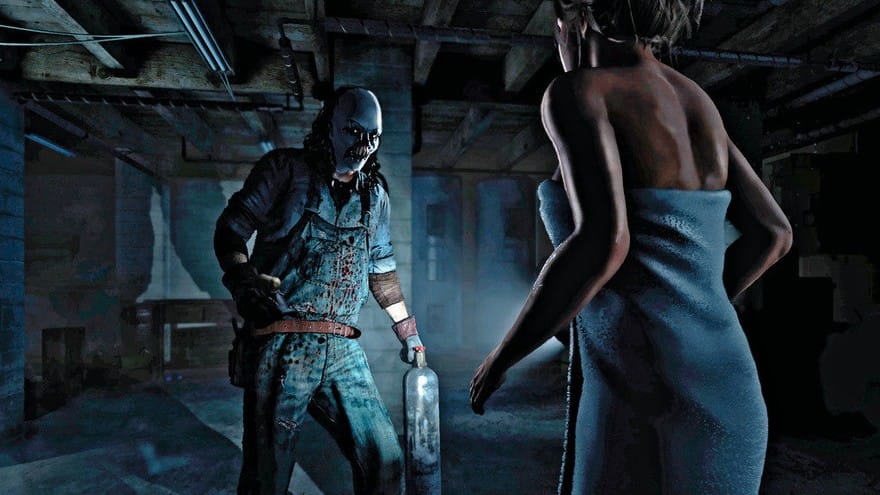

From what I’ve seen, Until Dawn conforms to this understanding of what audiences will and won’t be comfortable with, and then some. When they go off in their female/male pairings, the girls somehow always wind up in trouble and at the mercy of their male counterpart. He’s the bat-wielding idiot. She’s either falling into a cave or trapped on a ledge. The male character is then given the opportunity to heroically risk his life for her or leave her to her doom. I’m not condemning Until Dawn for this reason, but it’s definitely a complicating factor when it comes to using the final girl trope. Generally speaking, game designers don’t seem particularly interested in trying to get you to identify with girls. According to the executive producer of the Tomb Raider reboot, for example, male players don’t want to be Lara. They want to “protect” her. And you know what? Maybe that’s true for movies too. Maybe that’s just a possibility Clover didn’t consider enough.

Zach: I think “complicating factors” is a good way of looking at this. Clover offers up a ton of those, both intentionally and unintentionally (her analysis, like a lot of formative film theory, leans heavily Freudian). She draws strict gender lines in terms of identification, lines which don’t take into account the diversity of audiences who watch films or play videogames. The final girl is described thusly: “as the killer is not fully masculine, she is not fully feminine.” Later Clover calls her “ambiguous” in gender terms: masculinized femininity to the killer’s feminized masculinity. This suggests that horror hinges on difference. Familiar spaces made unrecognizable; the living body made into a corpse. In slasher terms, this means that deviation from the norm marks a given character as special. A woman who shows more tenacity and smarts than her counterparts is as different as the killer who sublimates his sexual impotence into phallic violence. So it makes perfect sense that they’re inevitably drawn together! It’s romantic, really.

horror hinges on difference

Until Dawn leans on the traditional gender dynamics of the slasher film; there’s no sense it intends to undermine them, not in the few hours I played. I don’t know who ends up as the final girl (although common sense suggests it’s Hayden Panettiere, but maybe they’ll Psycho us). You’re right; they could all make it out alive if you do really well. The developers have promised some seriously branching outcomes. With a cast of eight possible, controllable people, I’m not sure all this academic theory is so easily transposed. We need a Men, Women, and Dual Shocks.

Jess: I like it. I’ll be expecting a first draft of Men, Women, and Dual Shocks on my desk by spring of 2016. But what you’re pointing toward in terms of differences is that horror hinges on gender constructs and stereotypes—whether by breaking or abiding by them, the gender politics of slashers mixes our desires and fears into one twisted, throbbing ball of instinctual reactions. Maybe that’s why idiot teens fit the bill so perfectly, with all those hormones raging inside them. I guess all those screenshots of half-naked teen girls getting frisky with their hunky football jacket-wearing boyfriends makes more sense now. I think I’m starting to get you, Until Dawn.

There’s all sorts of funny things that happen with identification in Until Dawn regardless of gender, though, you’re right. It’s not often that games ask players to identify with multiple protagonists. It’s a risky move; one TellTale has (in my opinion) not been able to withstand in Game of Thrones. But adding the slasher element, along with the replayability, kind of turns typical avatar-player identification on its head. Because, sure, you might want to keep a toweled Hayden Panettiere alive the first time around out of some sort of avatar identification reflex or guttural fear response. But maybe the second time around, when you know the grandfather clock will chime to frighten you here, or that the boogeyman is just around the corner there, you’re inclined to look at this as a slasher flick you’re directing by controlling the actions of its actors. You’re less identifying with the actual character, and more like the technicians in Cabin in the Woods, influencing characters, placing them in the right situations to amp up drama or get a specific outcome.

On that note, how self-aware is Until Dawn about its absolutely ridiculous premise?

Zach: Self-awareness is kept to a blessed minimum: I will refrain from ragging on Cabin in the Woods, but this is played straighter and more sincerely, instead taking its cues from, say, You’re Next. Love for the genre is apparent, and in the opening credits I noticed indie horror fixtures Larry Fessenden and Graham Reznick wrote the game, which is a huge gesture of good faith, as well as another nod to the game’s cinematic aspirations. It’s ridiculous, yeah, but it’s not mugging at the audience.

Jess: I wonder how much you think Until Dawn imposes the “cinematic experience?” You touched a little on it earlier, in terms of the acting. But what about the rest of the production? The way I understand the butterfly mechanic that tracks your narrative path, both the big and small choices have effects on the story in ways you can’t predict. So you can’t straight-up direct this movie. You have to explore its possibility spaces, while also mitigating your own choices and sense of self through the characters. There’s a lot of debate among psychologists in terms of understanding exactly what’s happening with player-avatar identification. Some researchers theorize that while players obviously feel more ownership over their actions in games versus watching a movie (i.e. saying “I did this, I jumped there, I shot him”), it’s not clear whether they’re identifying with the character him or herself, or just expressing their own selves through the avatar as a vehicle. I imagine in Until Dawn, there’s a lot more distance in terms of identifying with the character the second time around. You’re still responsible for him or her, but you’re able to see the character as more of a vessel for story rather than your proxy.

Zach: So far it’s mostly concerned with primal fear responses and the balancing act of survival. Decisions come fast, and without much context. There is a difference between the first time you play through a scene and the subsequent attempts: the “good outcome” would presumably be guiding your current character to safety, but there’s no denying that the slasher genre is a play of violent tension and release. Kill scenes sharply punctuate long periods of tension carefully built by the filmmakers, and the kills provide their own appeal: over-the-top gore effects, outlandish scenarios, throbbing synthesized doom on the soundtrack. A “vessel for story” is a good way of putting it: you move the characters around to create the story you want.

a vessel for story rather than your proxy

Jess: This all reminds me of a study published by Indiana University back in July about the fear players feel in horror games. They found that fear response elicited from a certain player is dependent on both personality traits and production value like sound, image, and presence (which is a fancy word psychologists use to avoid PR terms like “immersion.”) The photo-realism of Until Dawn seems actually appropriate in context, unlike most other games. I imagine decision-making really helps with that feeling of being “inside the game” too since, unlike movies, you can’t just accuse a toweled Hayden Panettiere of being an idiot and getting herself killed. You are toweled Hayden Panettiere, so if you choose to hide under the bed instead of run, that’s your own stupid fault.

On a side note, the most concerning thing about this study is the fact that they found people with the lowest empathy levels are the most attracted to horror games. Presumably, because we can ignore the humanity of these characters getting put through a meat grinder (sometimes literally). Basically, Zach, we’re terrible people.

Let me ask you this: Did you always want to get the good outcome? Or did curiosity get the better of you on the second playthroughs? Because kill scenes in slasher movies are kind of like what the cumshot is to porn. We’re all here, waiting, watching this horror movie because it promised us gruesome death sequences. I’d feel really gypped if I left that movie theater having never seen one of these idiotic characters’ guts strewn all over the floor. Basically, I plan on being the most brutal Until Dawn player ever by trying to find the most cinematically tragic ways to murder these teens. The horror movie gods require a sacrifice, and I am more than willing to provide.

Zach: I had a hard time making deliberately “bad” decisions, to be honest, because I tend to be a perfectionist. I think, to your second point, that the way the game naturally picks up on cinematic language makes it difficult to dissociate the characters from you as a player. In fact, the combination of that learned genre response with player input makes it easy to identify with any given character at any point you drop into their story. It’s like a modular storytelling system: familiar scenarios + interactivity = tension, no matter who you’re playing as.

However: I haven’t seen anyone die, yet, which suggests there will be a lot of fake-outs or one The Burning-type massacre (please, please, please) to cull the cast, depending on what you do as a player. I don’t know that “player choice” is what horror necessarily needs; in fact helplessness is one of horror games’ strongest assets. The butterfly effect stuff is more about tracking your decisions in hindsight, like you say; it’s not as obvious as the “CLEMENTINE WILL REMEMBER THAT”-type stuff from Telltale games.

The game’s prodding you forward with fear, but it’s also creating characters that are rendered with just enough life to be sympathetic. It’s a balance the game is striking particularly well so far.

Jess: Fantastic, so, in conclusion, I’m a psychopath and Zach is actually a good person who wants to make sure toweled Hayden Panettiere makes it out alive and has a wonderful life with clothes on.

That’s an interesting point about helplessness, and that Indiana study agrees with you. The feeling of powerlessness that characterizes games like Amnesia: The Dark Descent obviously drives fear home. Helplessness has also done wonders for horror movies recently, too. It Follows only works because of the unbearable tension of inaction—which is really Jay’s only “choice.” She can only sit and wait— coupled with the constant threat of whatever It is. But you know, maybe choice doesn’t have to hinder the feeling of helplessness. Maybe being able to choose and then realizing you still can’t escape amps up the sense of powerlessness. No matter what you do, you’re just finding different ways to die. Though that fake-out Telltale method in decision-making games is wearing paper thin on me these days, and I imagine not being able to actually affect outcomes that much would put a damper on Until Dawn’s marketing campaign.

But you’ve only played the first few hours of the game, so we’re not sure how much the butterfly effect mechanic delivers on its ambitious promises. The director of Until Dawn recently claimed that no two players will ever have the same playthrough.

Zach: Look, slashers don’t have to be, like, good to be successful: they just need to get a few things right, and the formula works. They need atmosphere, or Tom Savini, or an awesome soundtrack. Until Dawn looks like it’s getting more than a few things right, and it could be good like slasher flicks are good.